"Captain Tom": Anne Lister, part 5

Anne Lister by John Horner, ca. 1830s. Image source: Calderdale Museums: Shibden Hall Paintings

A continuation of "Who taught you to kiss?": Anne Lister, part 4

From Paris to Copenhagen

Five months after Ann Walker had been bundled off to her sister and brother-in-law in Scotland—"'Heaven be praised,' said I to myself as I walked homewards, 'that they are off & that I have got rid of her & am once more free'" (18 February 1833)—Anne Lister headed to the continent. [1]

Her plan was to travel overland from Paris through Germany to Copenhagen. It took a full month and was hillier and at least four days of carriage travel longer than the standard itinerary through Antwerp and Amsterdam (and two weeks longer than taking a boat from Amsterdam). Her travel companion was 24-year-old Sophie Ferrall, a "pretty looking," "nice, sensible girl," whom she "liked. . .very well" (2-3 August 1833). Midway through the journey Anne had begun her standard seduction routine: "Playing with Miss Ferrall. Very good friends now. She sits on my knee tonight and has kissed me these three nights but I do it all very properly" (6 September 1833). But by the end of the journey Miss Ferrall's charms seem to have worn thin. On the eve of their arrival Anne wrote that she "was the most disagreeable girl I ever saw" (17 September 1833). [2]

Anne planned to stay in Copenhagen until the spring, and made use of her connections with Vere Cameron's sister Lady de Hageman and Sophie Ferrall's sister Countess Blucher to get introduced at the Danish court. But in late November Anne received word that her aunt's health was precarious. She returned to England, which involved a terrifying two-week voyage on stormy seas (and much seasickness).

When she arrived at Shibden in late December she received two surprises. The first was that her aunt was not in danger of imminent death. Anne wrote to Lady Louisa Stuart, "Found my aunt a great deal better than it was possible to expect from the very alarming accounts I had received" (21 December 1833). Aunt Anne would live for nearly three more years, dying at age 71 in October 1836. [3]

Anne's second surprise was that Ann Walker had returned from Scotland to Halifax. The two women reunited in early January at Lidgate. But Anne was wary of Ann's continued vacillation and low spirits. "The fact is, she is as she was before. . .I need to take someone with more mind and less money. . .she would be a great pother" (Sunday 5 January 1834). [4]

Anne hoped that a stay under the care of Dr. Stephen Belcombe, Mariana Lawton's brother, might help Ann's continued melancholy. It would also separate Ann from relatives who might object to the changes Anne was pressing her to make in her will. Each woman was to grant the other a life interest in her estate, a change that would ensure Anne's control over Ann's income in the event of her death, and vice versa. In mid-January Anne took Ann to York and left her in lodgings arranged by Dr. Belcombe at Heworth Grange.

The symbolic marriage

Despite her misgivings, Anne continued to press for commitment, and eventually Ann agreed that the couple would exchange rings:

Wednesday 12 February 1834: She is to give me a ring & I her one in token of our union. . . [5]

When the time for the ring exchange came, the gold band Anne wore as a symbol of her engagement to Mariana was repurposed for her new relationship with Ann:

Thursday 27 February 1834: I asked her to put [on my finger] the gold wedding ring I wore (and left her sixpence to pay me for it) [symbolically making it a gift when Ann returned it]. She would not give it me immediately but wore it till we entered the village of Langton and then put it on my left third finger in token of our union—which is now understood to be confirmed for ever tho' little or nothing was said. [6]

Anne gave Ann an onyx ring. Later in the 19th century onyx would be used in mourning jewelry, but in 1834 the association wasn't as established. Still, it seems something of an odd choice, until we remember that black was Anne's customary color: she wore it on almost every occasion.

Whether Ann thought of the ring exchange as a symbolic marriage in the same way as Anne isn't entirely clear. Anne had been urging Ann to move to Shibden permanently and rent out Lidgate, but Ann hesitated at taking such an irrevocable step:

Saturday 8 March 1834: Letter (3 pages and 2 1/4 pages crossed) from Miss Walker, Heworth Grange. . .'I am thinking about Lidgate, and will say more when I write next—will it be wise to irritate or brave public opinion just now? For the same reason, ought or can I accept your kind proposal about Shibden?' Her usual indecision—does she mean to make a fool of me after all?. . .Gave me (that is, bought for sixpence and put it on again) my ring languidly—and now declines taking the straight course of shewing our union, or at least compact, to the world. . .Does this seem as if she really thought us united in heart and purse? [7]

Perhaps Ann's reluctance to make their connection public made Anne determined to force the issue. While Ann was under Dr. Belcombe's care in York, Anne suggested that the two women undertake another symbolic ritual: taking communion together. (Anne had also shared communion with Mariana; see "I was now sure of the estate": Anne Lister, part 3.) On Easter Sunday they attended services at Holy Trinity Church Goodramgate, just a hundred yards from York Minster:

Sunday 30 March 1834: At Goodramgate Church at 10 35/"; Miss W— and I and [Anne's servant] Thomas staid the sacrament. . .The first time I ever joined Miss W— in my prayers—I had prayed that our union might be happy—she had not thought of doing as much for me. [8]

Interior of Holy Trinity Church, Goodramgate, York. Image source: York Civic Trust

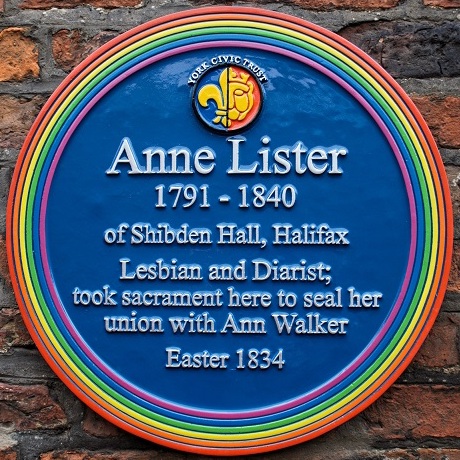

On Tuesday 24 July 2018 a blue plaque commemorating this event was installed at the Goodramgate entrance to the Holy Trinity churchyard. However, the plaque immediately excited controversy.

Original blue plaque commemorating Anne Lister and Ann Walker's communion. Photo credit: Keith Seabridge. Image source: BBC News

Julie Furlong, a lesbian feminist activist from Leeds, led a petition campaign to address what she saw as lesbian erasure in the wording of the plaque. She wrote, "Anne Lister was, most definitely, gender non-conforming all her life. She was also, however, a lesbian." It was also noted that the outer-to-inner colors of the rainbow border of the plaque reversed the top-to-bottom order of the colors on the Gilbert-Baker-designed rainbow flag. I'll also mention that identifying Anne Lister as an "entrepreneur" is stretching a point: she was a landowner whose income was mainly derived not from her coal-mining or business schemes, but from the rents she charged her tenants. [9]

The York Civic Trust quickly apologized, and after further consultation with the Yorkshire LGBTQ+ community, unveiled a revised plaque on 3 April 2019, the 228th anniversary of Anne Lister's birth.

Second blue plaque commemorating Anne Lister and Ann Walker's communion. Image source: York Civic Trust

The wording of the second plaque is also problematic. Anne Lister would not have thought of herself either as a lesbian (since the term was not used in the sense of female homosexual until the late 19th century), or primarily as a diarist—but, of course, that's how we think of her today.

Travel abroad and Ann Walker's move to Shibden

During Ann's stay in York, Anne gradually wore her down about travelling abroad, renting out Lidgate, and moving to Shibden Hall. This would become a recurring pattern in their relationship: Anne, the stronger personality and the more determined partner, pressing a reluctant Ann until she finally agreed, or at least acquiesced, to her plans.

At the end of May 1834, Anne removed Ann from Dr. Belcombe's care.

Friday 30 May 1834: I think Dr. B— seems now aware of the business between Miss W— and myself. [10]

Which "business" did Anne think that Dr. Belcombe understood: that the two women were sexual partners, or that Ann Walker had supplanted his sister Mariana as Anne's intended life companion? Whatever his understanding, he began to distance himself from the couple.

Meanwhile, Anne and Ann stopped briefly at Shibden, where Anne gave the steward Samuel Washington (who conveniently worked both for her and for Ann) orders to find a tenant for Lidgate. The two women then travelled to London, where Anne made the rounds of her aristocratic friends, but again without Ann. This suggests that among these women of higher social status it was now Anne who was concerned about revealing their union.

After London it was on to Paris and then Mont Blanc on the French-Italian border.

Monday 21 July 1834: Never in my life saw such a fidget in a carriage—she was in all postures & places till at last she luckily fell asleep for about an hour. [11]

Ann was clearly not the intrepid traveller Anne hoped for in her life companion.

At the end of August they arrived back at Shibden Hall. Ann's move out of Lidgate and into Shibden had been managed smoothly and was now a fait accompli, making it difficult for Ann's relatives to intervene. They weren't happy about it.

Thursday 4 September 1834: [During a call at Shibden, Ann's cousin] Mr W[illiam] P[riestley] mentioned Miss W—'s being here, and said how long she would remain was another thing. Seemed in bad temper about it; said A— had not consulted with any of her friends—had not mentioned her intention even to her aunt of Cliff-hill—evidently bitter against me.

Monday 8 September 1834: A— & I off to. . .Cliff-hill, and brought A— away at 5 35/"—no shaking hands with her aunt who had been crosser than ever. How tiresome! Gets upon poor A—'s nerves and undoes all good. Surely she will cease to care for such senseless scolding by and by—all sorts of bitterness against me. [12]

Ann's aunt, concerned that Anne Lister would inherit Ann's property, soon cut her niece out of her will.

The 1835 general election

On 29 December 1834 Parliament was dissolved and a general election was called; the election campaign in Halifax was hotly contested. The 1832 reform bill had expanded the franchise to male tenants who paid at least £50 a year in rent (still a small fraction of the population), and created Halifax as a new borough with two Parliamentary seats. Each elector could cast a vote for up to two candidates; voting for just one candidate, and so denying your second vote to one of the other candidates, was called "plumping," while voting for more than one candidate was called "splitting."

This new system created possibilities for the manipulation of rents to increase a landlord's influence. One of Anne Lister's tenants, Charles Howarth, paid an annual rent of £46. According to his later testimony, Anne raised his rent to £50, qualifying him as a West Riding elector, and then reimbursed him £2 every half year. Ballots were not secret—the names of electors and how they had voted were recorded in public "poll books"—and Anne and other landlords put intense pressure on their enfranchised tenants to vote for Tory candidates. [13]

Poll book for the Halifax borough election, 5 January 1835, "A correct list of all the electors who polled, distinguishing the candidates for whom they voted." Image source: From Weaver to Web: Online Visual Archive of Calderdale History

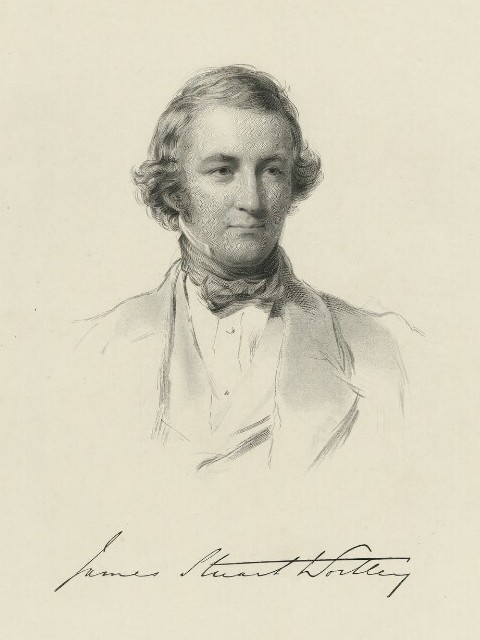

There were three candidates for the two Halifax seats: the incumbent Whig MP, Charles Wood; the Radical reform candidate Edward Protheroe; and the Tory candidate James Stuart Wortley, Lady Stuart's nephew and the great-great-grandson of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu. The Whigs and Radicals ("yellows") were allied against the Tories ("blues"). Nominations of the candidates and a show of hands favoring Wood and Protheroe took place at Halifax Piece Hall on Monday 5 January; Wortley then called for a poll, that is, an individual counting of the votes, which was held over the next two days.

Archibald James Stuart Wortley, engraving by William Holl Jr, after George Richmond, mid 19th century. Image source: National Portrait Gallery London

After the first day of polling Wood had a comfortable lead, and Protheroe was in second place; Wortley trailed Protheroe by more than a dozen votes. The second seat was still up for grabs, and more pressure was brought to bear on electors; there were also fears of fraud and election-stealing.

Tuesday 6 January 1835: Sad rough work in the town—almost all the blue flags torn in pieces by the orange, radical mob. . .Told A[quilla] Green [one of Anne's tenants] I did not want anyone to change his opinion against his conscience for me, but I had made up my mind to take none but blue tenants. . .

Wednesday 7 January 1835: Had [a visit from her tenant] John Bottomley—he is a good staunch blue plumper—has behaved very well—paid him for carting etc £6.16.4. . . [14]

John Bottomley was probably not the only Halifax elector whose landlord suddenly remembered to pay him for past work.

Poll book for the Halifax borough election, January 1835, showing John Bottomley's "plumper" for Wortley and Rawdon Briggs' split vote for Wood and Protheroe. Image source: From Weaver to Web: Online Visual Archive of Calderdale History

At the end of the second day of polling the word came from the election committee: Wood had won re-election with 336 votes, and Wortley had edged Protheroe by a single vote, 308 to 307.

We none of us thought the Radicals would push us so hard. . .the town was in a sad turmoil—the windows, glass & frames of many of the principal houses, inns & shops (blues) smashed to atoms—the 2 front doors of the vicarage broken down—Mr [Christopher] Rawson's carriage (the banker with [whom] Mr Wortley had been staying) completely broken up.

Thursday 8 January 1835: Had [a visit from] Charles Howarth—he wanted something to drink for himself & others: 11 or 12 (John Bottomley etc) workmen & pitmen in honor of Mr Wortley's election. . .Off to H[alifa]x at 12 40/" down the Old Bank—at the bottom of it a yellow mob of women & boys—asked if I was yellow—they looked capable of pelting me. 'Nay!' said I, 'I'm black—I'm in mourning for all the damage they have done.' This seemed to amuse them, & I walked quietly & quickly past. [15]

The Radicals would take their accusations of bribery, intimidation and fraud to Parliament, but to no avail. In the next general election two years later Protheroe would run again and defeat Wortley by a wide margin.

"Captain Tom"

An attack on Anne came almost immediately after the election. Because it also implicated Ann Walker, it probably wasn't from a member of Ann's immediate family. More likely it originated from a disappointed Whig or Radical supporter, or from someone with whom Anne had had business disputes. Interestingly, there was someone who fit both descriptions. Rawdon Briggs was a former Whig MP for Halifax; Wortley had been elected to the seat he had held from 1832 through 1834. And Briggs was also an investor in the Calder and Hebble Navigation canal who had been on the losing side against Anne at a recent shareholder's meeting.

Saturday 10 January 1835: [Samuel] Washington took coffee with us, and with some humming and ah-ing, pulled out of his pocket today's Leeds Mercury containing among the marriages of Wednesday last: 'Same day, at the Parish Church H[alifa]x, Captain Tom Lister of Shibden Hall to Miss Ann Walker, late of Lidget, near the same place.' I smiled and said it was very good—read it aloud to A— who also smiled and then took up the paper and read the skit to my aunt. . .A— did not like the joke—suspects the Briggs—so does my aunt. [16]

Marriage announcement of "Captain Tom Lister, of Shibden Hall" to "Miss Ann Walker, late of Lidgate." Leeds Mercury, Saturday 10 January 1835. Image source: British Newspaper Archive

Wednesday was, of course, the deciding day of the election. The notice soon appeared in newspapers in Bradford, Halifax, and even York. In Passions Between Women: British Lesbian Culture 1668-1801, Emma Donoghue notes that "tom" or "tommy" was a slang term for "a woman who had sex with women." Donoghue quotes from the anonymous satirical poem The Adultress (1773):

Woman with Woman act the Manly Part,

And kiss and press each other to the heart.

Unnat'ral Crimes like these my Satire vex;

I know a thousand Tommies 'mongst the Sex:

And if they don't relinquish such a Crime,

I'll give their names to be the scoff of Time. [17]

"Crime" is used here in the sense of a sinful or shameful act: unlike male homosexuality, sex between women was not actually criminalized.

Domestic dissension

Ann Walker was deeply religious, and her continuing sense that her sexual relationship with Anne was morally wrong was one of the many ways that the two women were dissimilar. That dissimilarity occasionally broke out in open dissension or small acts of sabotage. Two particular sore points with Ann seem to have been Anne's unwillingness to introduce her to her aristocratic friends in Vere Cameron's circle, and the solitary time Anne spent writing in her diary late into the night:

Wednesday 12 November 1834: F46° at 11 1/4 pm in my little dressing room, A— having taken away the key of my study [so] that I could not get in, meaning to make me by these means earlier in bed. [18]

Saturday 1 August 1835: . . .she did not like my not taking her to [visit Lady Stuart at] Richmond Park. . .She thought the sooner we parted the better. . .She by-and-by came round, kissed me etc. I took all well, but thinking to myself, 'There is danger in the first mention, the first thought, that it is possible for us to part—time will shew—I shall try to be prepared for whatever may happen.' [19]

This latter argument, probably referring to events of the previous summer when they visited London on their way to France, may have been a preemptive move on Ann's part; in August 1835 the two women were about to depart on another trip to London. But when they arrived in the city a few days later, once again Anne left Ann behind when visiting Lady Stuart, Lady Stuart de Rothesay, and Lady Gordon. Ann retaliated in one of the few ways available to her.

Saturday 8 August 1835: Home at 4 1/2. A— has locked up my journal—beside myself at the disappointment. [20]

Nonetheless, Anne went out by herself again that night to Lady Stuart's for dinner; Lady Vere Cameron was the only other guest. It would have made Ann even more furious to hear herself referred to as "my little friend," as Anne did with her London acquaintances.

There were also money disputes: Anne wrote that Ann was "queer about money" and "afraid I shall ruin her." Anne began to contemplate a future without her:

Friday 14 August 1835: A— sickish and reading the Psalms while I washed. She is queer and little-minded and I fear [for] her intellect. I must make the best of it—perhaps she will be with me as long as my father and aunt live, and then I see she will be no companion for me. I shall be at large again. [21]

Back at Shibden, Ann was clearly struggling. As the months passed the arguments between them continued.

Thursday 10 March 1836: A—. . .at last told me she had been unhappy the last two weeks—had not pleasure in anything, never felt as if doing right. Would not take wine—was getting too fond of it—afraid she should drink—was getting as she was before—afraid people would find it out, & began to look disconsolate. [22]

Jill Liddington thinks that "it" in the phrase "afraid people would find it out" refers to Ann's drinking; I wonder whether "it" relates either to her spiraling unhappiness ("getting as she was before") or to her sexual connection with Anne, about which she continued to have a powerful sense of guilt. Over this period and beyond many diary entries begin "No kiss."

The death of Jeremy Lister and the departure of Marian

On 3 April 1836 Anne was summoned to her father's bedroom at 4:40 a.m.; five minutes later he was dead. It was the morning of Anne's 45th birthday.

Sunday 3 April 1836: A— so low and in tears and her breath[ing] so bad, for she would take no luncheon—fancies she takes too much—that sleeping with her is not very good for me. Really I know not how it will end. At this rate I must give [her] up—she is getting worse and I cannot go on long without some amendment. [23]

Jeremy Lister's death meant that Anne's sister Marian would move out of Shibden and into Skelfler House in Market Weighton, which she had inherited. Anne had never liked Marian's presence at Shibden, a home Anne considered entirely hers. There was another issue as well: Marian had a long-term suitor, one Mr. Abbott. If they married and had children—Marian was not yet 40—it would complicate Anne's plan to give the unrelated Ann Walker a life interest in Shibden Hall. In the past Anne had done everything she could to discourage the match:

Monday 1 December 1834: She has made up her mind to marry Mr Abbott. . .I merely said she knew [what] I should think and what I should do. . .I said there would be no impropriety in her marrying six months after my father's death. . .not to stay long here after his death and not to announce to me her marriage—it would be enough [for me] to see it in the papers. . .that I sincerely wished her happy—that her best friend would probably [be] that person who mentioned me to her seldomest—and that, as for A— and myself, her (Marian's) name would not pass our lips any more. Marian was almost in tears—I could have been, but would not. Spoke calmly and kindly—said I should probably not tell my aunt as she would be much hurt and, as many things happened between the cup and the lip, perhaps the match might not take place—one of the parties might die. [24]

Kindness itself. In the end, whether or not Marian was willing to brave her sister's disapproval, she did not marry Mr. Abbott.

Changing the wills

Her father's death and her aunt's ill health gave additional urgency to Anne's desire for she and Ann to give each other a life interest in their respective estates. In early May they traveled to York to consult about their wills with Anne's lawyer Jonathan Gray. On the eve of the planned signing, Ann balked, and Anne was not above making veiled threats in order to convince her to go through with it:

Sunday 8 May 1836: A— thought it her duty to leave me—explanation—said I could not stand this—she must make up her mind and stick to it. . .The fact is, as I told her, she did not like signing her will. I told her she had best do it now and alter it afterwards. We should both look so foolish if she did not—it would make the break between us immediate—she had better take time [to think about it]. At last she saw, or seemed to see, her folly and said with more than usual energy she really would try to do better. [25]

The wills were signed the next day. After they were signed, Anne decided to make a codicil to enable Ann to sell some of the Shibden properties, if necessary, in case Anne died with substantial debts. Generally a life-interest would not include the ability to sell any of the property; perhaps Anne did this to calm Ann's fears that her own estate might end up bearing the costs of Anne's spending on Shibden. The codicil was signed the next afternoon, and then the couple returned to Shibden, arriving about 40 minutes before midnight. Marian had left Shibden early that morning, avoiding any awkward goodbyes.

Anne Lister's death and the fate of Shibden Hall

In October 1836 Anne's beloved Aunt Anne passed away, leaving Anne in full possession of the Shibden estate and its income. She did not have many years to enjoy it, however. In June 1839 she and Ann left on an extended trip to Russia. They travelled for more than a year, taking in St. Petersburg and Moscow and then heading further south. By the late summer of 1840 they had arrived at Kutaisi in the Imereti region of western Georgia. There a catastrophic accident occurred: Anne was apparently bitten by a disease-carrying tick and died a few days later of a raging fever. She was only 49.

In mental energy and courage she resembled Lady Mary Wortley Montagu and Lady Hester Stanhope; and like these celebrated women, after exploring Europe, she extended her researches to the Oriental regions, where her career has been so prematurely terminated. We are informed that the remains of this distinguished lady have been embalmed and that her friend and companion, Miss Walker, is bringing them home by way of Constantinople for interment in the family vault. . . (Halifax Guardian, 31 October 1840) [26]

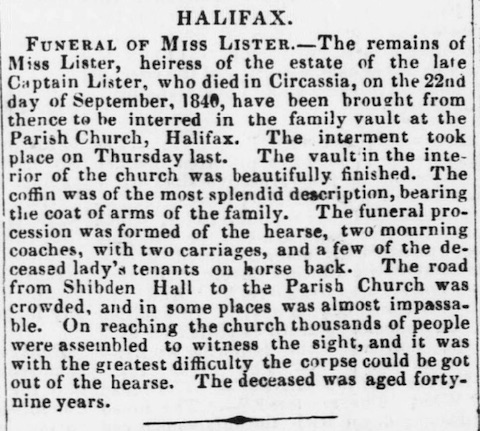

It took a full six months for Anne Lister's coffin to make it back to Halifax. The Leeds Times and other local papers gave an account of the funeral:

Leeds Times, 1 May 1840. Image source: British Newspaper Archive

Ann Walker now received a life tenancy at Shibden Hall and a life interest in the Shibden estate rental income. However, the task of managing both her own estate and Shibden proved difficult. She and Anne had also been embroiled in a long-running dispute with her brother-in-law Captain George Mackay Sutherland over the division of the Walker estate jointly inherited by Ann and her sister Elizabeth. Sutherland also did not approve of Ann having given Anne a life interest in her portion of the estate (the life interest most likely would have gone to him instead, as a trustee for his son Sackville). With Anne dead, Captain Sutherland saw an opportunity to gain control of both the Walker and Shibden estates.

Ann's sister Elizabeth Sutherland, probably at the direction of her husband, brought in the lawyer Robert Parker and Ann's previous caregiver Dr. Stephen Belcombe to have Ann declared of unsound mind. Fifteen years earlier, Ann's cousin by marriage Eliza Priestley had confessed to Anne Lister that the family despaired of her sanity:

Thursday 28 August 1828: Miss Walker's illness likely to be insanity—her mind warped on religion. She thinks she cannot live—has led a wicked life, etc. Had something of this sort of thing occasioned by illness at seventeen, but slighter. The illness seems to in fact be a gradual tendency to mental derangement. [27]

And in 1822 Eliza Priestley's husband William made a comment to Anne Lister about his uncle John Walker, Ann's father: he said he was a 'madman...[who] blackguarded his wife and daughters' (Tuesday 9 July 1822). "Blackguarding" has a broad array of meanings, but chief among them is to behave dishonorably or immorally towards someone; it might involve anything from openly keeping mistresses to verbal, physical, psychological, or other forms of abuse.

Whether Ann had an inherent tendency towards mental illness, had been traumatized by abuse she had suffered from her father or the Rev. Mr. Ainsworth (see "Who taught you to kiss?": Anne Lister, part 4), or was just difficult and inconvenient, in 1843 she was taken from Shibden Hall. It was a forcible removal: a constable had to take a locked door off its hinges. Ann was sent to Dr. Belcombe's asylum near York, where Anne Lister's former lover Eliza Raine resided as well. Shibden Hall was occupied by tenants, and, after Elizabeth's death in 1844, by Captain Sutherland. He did not live there long, however: he died at Shibden in 1847, at age 49.

Ann lived until 1854. On her death at age 51, her 23-year-old nephew Sackville Sutherland inherited her half of the Walker estate, uniting it with his mother Elizabeth's portion. Since Ann's interest in Shibden Hall and its rents ended with her death, that estate now reverted to Anne's distant male relative John Lister, who was living in Wales.

In 1855 he and his family moved to Shibden, and on his death in 1867, his son John inherited. This is the John Lister who discovered Anne Lister's hidden, encoded diary, and after learning what it contained, refused to burn it, enabling us to read Anne Lister's incredibly rich, detailed, frank, but often unflattering record of her remarkable life.

Next time: "No historical interest whatever": Anne Lister, part 6

Other posts in this series:

- "I only love the fairer sex": Anne Lister, part 1

- "It was all nature": Anne Lister, part 2

- "I was now sure of the estate": Anne Lister, part 3

- "Who taught you to kiss?": Anne Lister, part 4

Sources for and works discussed in this series:

I Know My Own Heart: The Diaries of Anne Lister, [1816–1824,] Helena Whitbread, ed. Virago, 1988/2010 (as The Secret Diaries of Miss Anne Lister), 422 pgs.

No Priest But Love: Excerpts from the Diaries of Anne Lister, 1824–1826, Helena Whitbread, ed. NYU Press, 1992, 227 pgs.

Jill Liddington, Presenting the Past: Anne Lister of Halifax 1791–1840, Pennine Pens, 1994, 76 pgs.

Female Fortune: Land, Gender and Authority: The Anne Lister Diaries and Other Writings, 1833–1836, Jill Liddington, ed. Rivers Oram Press, 1998, 298 pgs.

The Secret Diaries of Miss Anne Lister, written by Jane English, directed by James Kent, starring Maxine Peake as Anne Lister, BBC, 2010, 92 mins.

Gentleman Jack, written and directed by Sally Wainwright and others, starring Suranne Jones as Anne Lister, BBC, 2019–2022, 16 episodes, 950 mins.

Anne Choma, Gentleman Jack: The Real Anne Lister, Penguin, 2019, 258 pgs.

- Jill Liddington, ed., Female Fortune, p. 72. As ever, the quotes from the diaries in italics were written in code.

- Anne Choma, Gentleman Jack, pp. 219, 228, 229. According to Choma, " [In 1841] Sophie Ferrall went on to marry Federico Confalonieri, the Italian revolutionary. . .In the years after Confalonieri's premature death [at age 61 in 1846], she was able to count Rossini, Verdi, Liszt, Victor Hugo, Balzac and Alexis de Tocqueville among her acquaintances" (p. 229).

- Gentleman Jack, p. 243.

- Female Fortune, p. 85.

- Female Fortune, p. 93.

- Female Fortune, p. 95.

- Female Fortune, p. 98. A "crossed" letter was one in which, as a paper- and postage-saving measure, the writer turned a page sideways after filling it and wrote additional lines that were perpendicular to the first ones.

- Female Fortune, p. 100.

- FiLiA podcast #30: Julie Furlong: https://www.filia.org.uk/latest-news/2019/7/17/filia-meets-julie-furlong. The discussion of the Anne Lister plaque campaign and Gentleman Jack begins at 35:57 and runs through 42:35.

- Female Fortune, p. 107.

- Female Fortune, p. 109.

- Female Fortune, pp. 110-111.

- Female Fortune, p. 51.

- Female Fortune, p. 140.

- Female Fortune, pp. 141-142.

- Female Fortune, p. 143.

- Quoted in Emma Donoghue, Passions Between Women: British Lesbian Culture 1668-1801, HarperCollins, 1993, p. 5. The Adultress was "Printed for S[amuel] Bladon, in Paternoster Row"; Bladon was probably the author.

- Female Fortune, p. 126.

- Female Fortune, pp. 185-186.

- Female Fortune, p. 186.

- Female Fortune, pp. 186-187.

- Female Fortune, p. 210.

- Female Fortune, p. 227.

- Female Fortune, pp. 131-132.

- Female Fortune, pp. 233-234.

- Quote from the Halifax Guardian from Helena Whitbread, ed., No Priest But Love: Excerpts from the Diaries of Anne Lister, 1824-1826, New York University Press, 1992, p. 206.

- Gentleman Jack, p. 67-68.

No comments :

Post a Comment