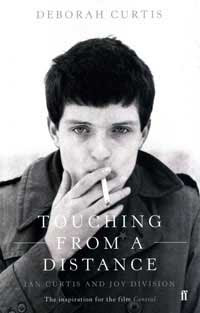

Touching From A Distance: Ian Curtis and Joy Division

Touching from a Distance (Faber, 2007, originally published 1995) is Deborah Curtis' memoir of her life with Ian Curtis, the lead singer of Joy Division. She and Ian married in 1975, while they were still teenagers. Deborah became pregnant with their daughter Natalie in mid-1978, just as Joy Division released its first record (the four-song EP An Ideal for Living), and gave birth in April 1979, just two months before the release of the band's first full-length album (Unknown Pleasures). Under the enforced separation of touring and the pressures of Ian's newly diagnosed epilepsy, his ongoing relationship with another woman, and the bands' growing fame, Deborah and Ian drifted further apart. On May 18, 1980, the night before he was scheduled to leave on Joy Division's first US tour, Ian Curtis committed suicide.

Touching from a Distance (Faber, 2007, originally published 1995) is Deborah Curtis' memoir of her life with Ian Curtis, the lead singer of Joy Division. She and Ian married in 1975, while they were still teenagers. Deborah became pregnant with their daughter Natalie in mid-1978, just as Joy Division released its first record (the four-song EP An Ideal for Living), and gave birth in April 1979, just two months before the release of the band's first full-length album (Unknown Pleasures). Under the enforced separation of touring and the pressures of Ian's newly diagnosed epilepsy, his ongoing relationship with another woman, and the bands' growing fame, Deborah and Ian drifted further apart. On May 18, 1980, the night before he was scheduled to leave on Joy Division's first US tour, Ian Curtis committed suicide.

This is an angry book. And it's not just survivor's anger. Deborah is angry about Ian's mercurial moods, his controlling behavior, his absences, his emotional remoteness from both her and their daughter, his drug use, and his infidelity. Of course, it's clear that Ian could be a difficult person. But strangely, I can hardly recall the word "depression" occurring in the text, although Ian's lyrics are saturated with despair. And Ian's incredible sensitivity, remarked on by everyone who knew him, only surfaces occasionally here. To be fair, Deborah does record moments of generosity, warmth and caring, but in the main she seems to have consciously taken aim at the icon "Ian Curtis" and tried to smash it.

But there are two things missing from this portrait. One is that Ian largely excluded her from his creative life: he didn't discuss his lyrics with her, and she wasn't present at most of the band's rehearsals, performances or recording sessions. In short, Ian Curtis the artist is absent.

The second thing that's missing is self-examination: a searching look at her own behavior, motivations and choices. Did she get pregnant in the hope of making a shaky relationship stronger? Or did she feel that a child would draw Ian away from the insular world of the band, which more and more excluded her? Or did she just not realize how all-consuming Joy Division's increasing success would be? All she says is that "hearing other women at the college talk about children had made me broody....What [Ian] wanted most in the world was for people to be happy. If having a baby would make me happy, we could have a baby" (p. 65). It seems incredible that either of their motivations could have been that simple.

The inescapable feeling is that they were a tragically mis-matched couple from the start. By her own account Deborah longed for comfortable domesticity, while Ian's overwhelming focus was his music. Late nights, long rehearsals, gigs, touring, and the inevitable drugs and groupies don't lend themselves to a stable home life. This is something that Deborah says only occurred to her "with hindsight," but the disjunction between her "ideal for living" and Ian's strikes the reader on almost every page.

And there are hints scattered throughout the book that Ian wasn't the only difficult personality in this relationship. In a passage about an incident from the first year of their married life which reveals more, perhaps, than she may realize, she writes: "Ian found it difficult to continue with his writing because there was nowhere he could find a comfortable solitude. The restrictions of living with relatives were lifted and our relationship would have been stormy if not for Ian's refusal to communicate with me. This was one way in which he would avoid confrontation. One night he turned his back to me in bed once too often. I bit into his back in desperation. Shocked by the faint tinge of blood in my mouth, I was rewarded by being kicked on to the floor" (p. 35). I can't get over the horror of the sentence "our relationship would have been stormy if not for Ian's refusal to communicate with me"--it speaks of an almost complete breakdown of communication and affection on both sides. Notice that, even though Ian can't find the solitude to create (they had their own house at this point, so his lack of solitude probably related to her demands for his attention), and though he has retreated into silence to avoid her anger, she sees herself as the only one "in desperation." She has perhaps unconsciously inverted Ian's lyrics from "Love Will Tear Us Apart":

"You lie back on your side, all my failings exposed,

There's a taste in my mouth, as desperation takes hold

That something so good, just can't function no more..."

After reading this memoir, it's tempting to see this song about a dying relationship as Ian's portrait of their marriage: it speaks of routine, resentment, stunted emotions, and two people growing ever further apart but unable to break free of each another.

Deborah Curtis' book is the basis of Anton Corbijn's Joy Division film Control (2007), and she is listed (along with Tony Wilson, founder of Joy Division's label Factory Records) as a co-producer. I haven't yet seen the film, but I hope that in addition to documenting the difficulties of the Curtis' personal lives, it does justice to what's missing from the book: the emotional power of the music that Ian Curtis and the other members of Joy Division created together.