Hamnet

Regular readers of E&I may be aware that I don't post with great frequency about contemporary fiction. Of the 141 works of fiction listed on this blog's Book Index only 56, or 40%, were first published after 1950 (which is stretching the definition of "contemporary" quite a bit). This is not because I don't read contemporary fiction. I regularly scan book reviews, make lists, and seek out new works. Almost inevitably, though, I am disappointed by the quality of the writing. Reading 18th- and 19th-century novels may have spoiled me for modern prose.

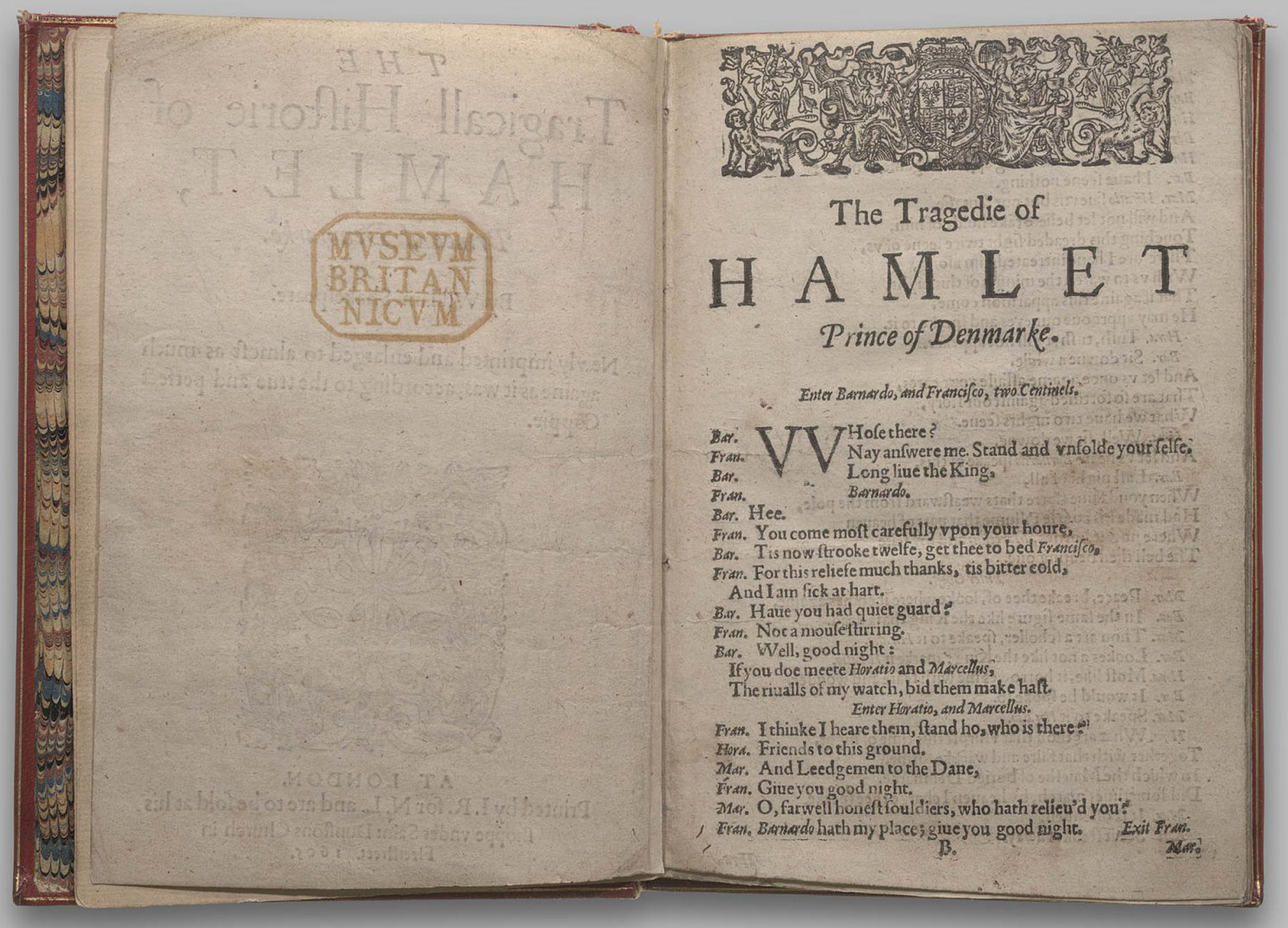

These thoughts are occasioned by my encounter with Maggie O'Farrell's Hamnet (Knopf, 2020), which imagines the impact of the death of the eleven-year-old Hamnet on his mother Agnes and his father William. [1] The year is 1596; four years later, his father will appear as the Ghost in his new play The Tragedie of Hamlet, Prince of Denmarke (the names Hamlet and Hamnet were interchangeable; the Ghost is that of Hamlet's father, also named Hamlet).

Opening page of The Tragedie of Hamlet from actor David Garrick's copy of the Second Quarto (1605). Image source: The British Library

O'Farrell's novel has been highly, not to say extravagantly, praised. It won the 2020 Women's Prize for Fiction (the jury called it "truly great") and was named by the New York Times as one of the 10 Best Books of 2020, only half of which are fiction. It was also the first book mentioned on the The Guardian's Best Fiction of 2020 list and was tied for fifth on LitHub's Ultimate Best Books of 2020 list. The only dissent from the near-universal commendation came from the Man Booker Prize judges, who omitted it from their 2020 longlist.

In Geraldine Brooks' New York Times review she wrote that you do not "go after the private life of the Bard of Avon with a casual regard for English prose." Well, here are some passages from the first pages of the book, whose narrative text begins on page 5:

- Hamnet "sighs, drawing in the warm, dusty air" (p. 5). But when you sigh you breathe out, not in. ("A long deep and audible exhalation" is how "sigh" is defined by the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary.) "Hamnet draws in the warm, dusty air and sighs" might work; the reverse doesn't.

- When in the next sentence Hamnet steps out into the street, "the noise of barrows, horses, vendors, people calling to each other, a man hurling a sack from an upper window doesn't reach him" (p. 5). And yet when he enters his grandfather's house next door, he hears "the creaking of beams expanding gently in the sun, the sigh of air passing under doors, between rooms, the swish of linen drapes, the crack of the fire, the indefinable noise of a house at rest, empty" (p. 6). So within the space of a few sentences Hamnet is described as both utterly oblivious to the world around him and extraordinarily sensitive to it.

- About "the crack of the fire": On the first page we are told that "it is a close, windless day in late summer" and on the second page that "the heat of the day" is making Hamnet sweat so heavily it runs "down his back." On a swelteringly hot summer afternoon would a fire be kept burning, and would it have been left untended in an empty house?

- And "the sigh of air passing under doors, between rooms, the swish of linen drapes": if the day is windless, would a breeze be moving audibly through the house and stirring the drapes enough to make them swish? And as we will soon learn, Hamnet's grandfather is a leather tanner and wool merchant who is in financial distress; would his house have linen drapes, or would he be more likely to use the materials at hand? Just asking.

- The sounds of the empty house are described as "indefinable noise," although we've just read a detailed list of the specific sounds Hamnet detects (in what way, then, are they "indefinable"?). On the same page its smell is described as "indefinably different" from the rooms where Hamnet lives with his mother and sisters. Leaving aside the rather uninspired repetition, are we perceiving Hamnet's thoughts, and if so, would an 11-year-old boy in the 16th century really think that sounds or smells were "indefinable"? (Apart from the unlikeliness of "indefinable" occurring to an 11-year-old boy, according to the Shorter Oxford the word doesn't even come into use until a century after Hamnet is born.)

- Speaking of repetitions, in the first pages we read the phrases "the noise of barrows" (p. 5), "the noise and welter of the courtyard" (p. 6), "he makes this noise" (p. 6), "the indefinable noise of a house" (p. 6), "the noise of a bird in the sky" (p. 7), "a noise, a slight shifting or scraping" (p. 9), and "he hears a noise. . .the definite noise of another human being" (p. 11).

Repetition can be an effective fictional technique: the word "fog" occurs 22 times in the first chapter of Dickens' Bleak House, along with "foggy" and "fog-bank," as the murky case of Jarndyce and Jarndyce is introduced:

Fog everywhere. Fog up the river, where it flows among green aits and meadows; fog down the river, where it rolls defiled among the tiers of shipping and the waterside pollutions of a great (and dirty) city. Fog on the Essex marshes, fog on the Kentish heights. Fog creeping into the cabooses of collier-brigs; fog lying out on the yards and hovering in the rigging of great ships; fog drooping on the gunwales of barges and small boats. Fog in the eyes and throats of ancient Greenwich pensioners, wheezing by the firesides of their wards; fog in the stem and bowl of the afternoon pipe of the wrathful skipper, down in his close cabin; fog cruelly pinching the toes and fingers of his shivering little 'prentice boy on deck. Chance people on the bridges peeping over the parapets into a nether sky of fog, with fog all round them, as if they were up in a balloon and hanging in the misty clouds. . .

In Hamnet the repetitions of "noise" in the opening pages are (I'm guessing) meant as a deliberate contrast with the last words of the chapter: "there is nothing: only silence" (p. 24), which echo the last words of Hamlet in Shakespeare's play: "the rest is silence." But earlier in the chapter when Hamnet was listening for an answer to his calls, he was keenly aware of all the faint sounds in his grandfather's empty house. He is listening just as intently now: why does he hear "only silence"?

Never can there come fog too thick, never can there come mud and mire too deep, to assort with the groping and floundering condition which this High Court of Chancery, most pestilent of hoary sinners, holds this day in the sight of heaven and earth. [2]

- "Every life has its kernel, its hub, its epicentre" (p. 9). After five pages written largely in free indirect style, as though we are listening to Hamnet's thoughts, this is an abrupt intervention from an omniscient narrator. One, moreover, born after the mid-20th century when "epicentre" was first used to mean "the centre or heart of something," according to (yes) the Shorter Oxford, which also tells us that the word "epicentre" was coined (by the Irish seismologist Robert Mallet, says Wikipedia) in the late 19th century.

The use of "epicentre" could be a deliberate signalling to the reader that the narrator shares our time frame rather than that of the characters. This is a variant of a technique called "the intrusive narrator," and is used, for example, by Michel Faber in The Crimson Petal and the White (2002), set in Victorian London. From that novel's opening:

Watch your step. Keep your wits about you; you will need them.

Hamnet is similarly written almost entirely in the present tense, but unlike Faber's novel it is almost entirely in free indirect style. O'Farrell does not seem to have intended to employ an intrusive narrator, but rather to immerse the reader fully in the characters' world and thoughts. This is why I find an anachronism like "epicentre" so jarring.

This city I am bringing you to is vast and intricate, and you have not been here before. You may imagine, from other stories you've read, that you know it well, but those stories flattered you, welcoming you as a friend, treating you as if you belonged. The truth is that you are an alien from another time and place altogether.

When I first caught your eye and you decided to come with me, you were probably thinking you would simply arrive and make yourself at home. Now that you're actually here, the air is bitterly cold, and you find yourself being led along in complete darkness, stumbling on uneven ground, recognising nothing. . .

Apart from the pale gaslight of the streetlamps at the far corners, you can't see any light in Church Lane, but that's because your eyes are accustomed to stronger signs of human wakefulness than the feeble glow of two candles behind a smutty windowpane. You come from a world where darkness is swept aside at the snap of a switch, but that is not the only balance of power that life allows. Much shakier bargains are possible. [3]

I recognize that my comments on these examples—all taken from the novel's first chapter—will exasperate or infuriate many people. They will think I'm nit-picking: what does it matter if O'Farrell's writing is at times unwittingly anachronistic, dully repetitious, disconcertingly inconsistent, or simply wrong? They are welcome to find her novel, as the cover blurbs describe it, "a thing of shimmering wonder" (David Mitchell), "beautifully imagined and written" (Claire Tomalin), "finely written" (Sarah Moss), full of "flawless sentences" (Emma Donoghue), or "one of the best novels I've ever read" (Mary Beth Keane).

But for me details matter, especially in historical fiction, and most especially when they are so carefully specified and emphasized by the author. And as regular readers know, I'm one of those unfortunates for whom lapses like the ones I've listed are so grating they render imaginative entry into O'Farrell's fictional world impossible. [4]

- As O'Farrell explains in her Author's Note, "Most people will know [Hamnet's] mother as 'Anne,' but she was named by her father, Richard Hathaway, in his will, as 'Agnes,' and I decided to follow his example." I wonder whether a woman wouldn't more likely be called by her preferred name in the records relating to her adult life and death than in her father's will; certainly the few other documents that exist indicate that she was known as Anne.

- Charles Dickens, Bleak House, Chapter I, "In Chancery." http://gutenberg.org/cache/epub/1023/pg1023.txt

- Michel Faber, "The Crimson Petal and the White, Episode One," serialization in The Guardian, 31 May 2002. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2002/jun/01/fiction. For a brief discussion of the intrusive author/narrator in Faber's novel and its antecedents in Fielding, Eliot, and other writers, see John Mullan, "Book club: Follow my leader," The Guardian, 17 October 2003. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2003/oct/18/1

- For more evidence, if any is needed, see "On ignoring the big picture for the nagging detail" (on Michael Chabon's The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay) in my post on Nick Hornby's "Stuff I've Been Reading."