Six months with Jane Austen: Emma and the fate of unmarried women

Emma Woodhouse, handsome, clever, and rich, with a comfortable home and happy disposition, seemed to unite some of the best blessings of existence; and had lived nearly twenty-one years in the world with very little to distress or vex her. [1]Of all of Jane Austen's heroines, Emma is the one that most seems to be a kind of fantasy figure. All of Austen's other heroines come either from wealthy families in newly straitened circumstances (Elinor and Marianne Dashwood in Sense and Sensibility, Anne Elliot in Persuasion), or from families that inhabit the lower levels of the gentry or pseudo-gentry and thus are already in relatively straitened circumstances (Elizabeth and Jane Bennet in Pride and Prejudice, Fanny Price in Mansfield Park, Catherine Morland in Northanger Abbey).

But Emma is different. As we learn in the early stages of the novel, Emma is "the heiress of thirty thousand pounds," and this gives her a freedom unique among Austen heroines: in order to have a financially secure future, she does not have to marry. In fact, she "'declares she will never marry'":

'I have none of the usual inducements of women to marry...Fortune I do not want; employment I do not want; consequence I do not want: I believe few married women are half as much mistress of their husband's house as I am of Hartfield; and never, never could I expect to be so truly beloved and important; so always first and always right in any man's eyes as I am in my father's.' [2]But if Emma Woodhouse has "'very little intention of ever marrying at all,'" there is another Emma in Austen's work who provides a more sobering picture of the possible fate awaiting an unmarried woman: Emma Watson, heroine of the fragment The Watsons (written around 1805). After the uncle who has raised her dies, and her widowed aunt makes an "imprudent" remarriage, Emma Watson returns to her birth family's home and, like Fanny Price when she makes a similar journey in Mansfield Park, discovers that

...she was become of importance to no one, a burden on those whose affections she could not expect, an addition in a house already overstocked, surrounded by inferior minds, with little chance of domestic comfort, and as little hope of future support. [3]It is a bleak picture of superfluousness, poverty, and a lack of privacy and solitude combined with social, emotional and intellectual isolation. And in Emma, a similar future, or present, is faced by each of the single women who do not share Emma Woodhouse's happy state of financial independence.

The "parlour-boarder": Harriet Smith

Harriet is 17, and "the natural daughter of somebody. Somebody had placed her, several years back, at Mrs. Goddard's school, and somebody had lately raised her from the condition of scholar to that of parlour-boarder." [4] Although Harriet's unseen and unknown guardian—presumably her biological father—pays extra so that she can live as a part of the proprietor's household and have the use of their sitting room, she is without social connections or financial means of her own. She is utterly dependent on her mysterious benefactor, a situation that leaves her future highly uncertain.

Mr. Knightley tells Emma that Harriet "'may be a parlour-boarder at Mrs. Goddard's all the rest of her life,'" but he is wrong: Harriet is only likely to be a parlour-border for the rest of her father's life. When he dies, Harriet's "'very liberal'" allowance is likely to be abruptly cut off. As Mr. Knightley notes, she has "'probably no settled provision at all'"—that is, she has been given no money of her own and cannot expect any legacy from her father. Wills were and are public documents, and a father who cannot acknowledge Harriet while he lives is unlikely to expose his family to scandal when he dies. [5]

Jane Austen was herself a parlour-boarder. When she was nine, she and her sister Cassandra (then twelve) were sent as parlour-boarders to Abbey House School in Reading. So Jane was intimately familiar with the odd in-between status of parlour-boarders, who lived in the proprietor's household, but were not a part of it. Jane also knew what it meant to be dependent: after her father died in 1805, she had to rely almost entirely on her brothers for financial support (at least until she began to receive a modest income from her writing).

Harriet, of course, has no relatives she can call on. After her father's death, if she remains unmarried it's likely that she will be forced to earn her means of livelihood; she will be "'left in Mrs. Goddard's hands to shift as she can.'" [6] Without useful accomplishments, knowledge or skills, she will face a future in which her circumstances are drastically reduced—an existence much like that of another character in the novel, Miss Bates.

The "old maid": Miss Bates

Miss Bates is the daughter of Highbury's former vicar. She lives with her elderly mother and one servant above a Highbury shop in a "very moderate-sized apartment, which was every thing to them." Miss Bates must live "in a very small way...She had never boasted either beauty or cleverness. Her youth had passed without distinction, and her middle of life was devoted to the care of a failing mother, and the endeavour to make a small income go as far as possible." We are told that they have "'barely enough to live on,'" and indeed, Mr. Knightley regularly sends them food from his estate. [7]

Miss Bates' situation is not unlike that of Jane Austen herself: she never married, of course, and at the time that Emma was written she lived with Cassandra and their widowed mother in Chawton Cottage, a house on the grounds of an estate owned by her brother Edward. While the Austen women were not as poor as Mrs. and Miss Bates, they too had to live within limited means.

Miss Bates' status as a poor old maid is viewed with horror by Harriet Smith and disdain by Emma:

'But then, to be an old maid at last, like Miss Bates!'It is Mr. Knightley, of course, who reminds Emma that Miss Bates "'is poor; she has sunk from the comforts she was born to; and, if she live to old age, must probably sink more. Her situation should secure your compassion.'" [9]

'That is as formidable an image as you could present, Harriet;...[but] I shall not be a poor old maid; and it is poverty only which makes celibacy contemptible to a generous public! A single woman, with a very narrow income, must be a ridiculous, disagreeable old maid!' [8]

The governess: Jane Fairfax

Another potential future for unmarried women without incomes is exemplified by Jane Fairfax, the niece of Miss Bates. Orphaned as a young girl, Jane Fairfax was taken to live with the family of Colonel Campbell, the commanding officer of her father's regiment:

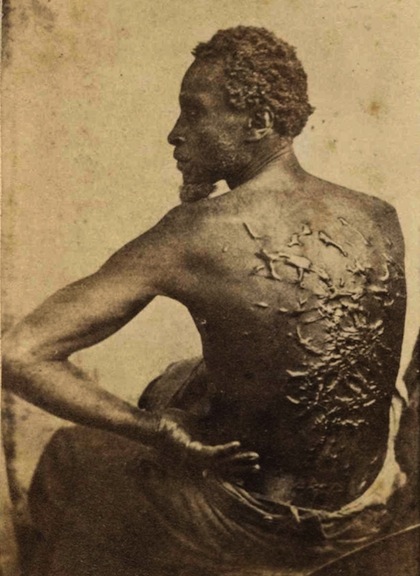

The plan was that she should be brought up for educating others; the very few hundred pounds which she inherited from her father making independence impossible...By giving her an education, [Colonel Campbell] hoped to be supplying the means of respectable subsistence hereafter. [10]Jane Fairfax is intended to earn her living as a governess, one of the few "means of respectable subsistence" available to women of the pseudo-gentry. This is no enviable position, as Jane makes clear to Mrs. Elton, the former Miss Hawkins, whose father, "a Bristol—merchant, of course, he must be called," is undoubtedly involved in the slave trade:

'I am not at all afraid of being long unemployed. There are places in town, offices, where inquiry would soon produce something—Offices for the sale—not quite of human flesh—but of human intellect.'Given Jane Austen's feelings about the slave-trade, clearly implied in Mansfield Park, the parallel Jane Fairfax suggests with the exploitative "governess-trade" is highly suggestive. And the hyperbolic effusions of Mrs. Elton about the position she ultimately arranges for Jane do not allay our suspicions of the circumstances that await her:

'Oh! my dear, human flesh! You quite shock me; if you mean a fling at the slave-trade, I assure you Mr. Suckling [Mrs. Elton's brother-in-law] was always rather a friend to the abolition.'

'I did not mean, I was not thinking of the slave-trade,' replied Jane; 'governess-trade, I assure you, was all that I had in view; widely different certainly as to the guilt of those who carry it on; but as to the greater misery of the victims, I do not know where it lies.' [11]

'...there are not such elegant sweet children anywhere. Jane will be treated with such regard and kindness!—It will be nothing but pleasure, a life of pleasure.—And her salary!—I really cannot venture to name her salary to you, Miss Woodhouse. Even you, used as you are to great sums, would hardly believe that so much could be given to a young person like Jane.'Even in those rare instances when governesses were decently paid, theirs was hardly "a life of pleasure." They were frequently isolated within the household. As David Selwyn writes, "The isolation experienced by a governess was often very demoralizing: treated by her employer, to whose class she naturally belonged, as a social inferior, and yet distrusted by the servants, she often found her position in the household to be very lonely." [13]

'Ah! madam,' cried Emma, 'if other children are at all like what I remember to have been myself, I should think five times the amount of what I have ever yet heard named as a salary on such occasions, dearly earned.' [12]

While Emma's governess, Anne Taylor, becomes her friend and confidante and is treated like a member of the Woodhouse family, such an outcome was highly unusual. Far more typical were the experiences that Anne Brontë drew on three decades later for her novel Agnes Grey. As Elizabeth Gaskell wrote of a conversation she held with Anne's sister Charlotte,

She said that none but those who had been in the position of a governess could ever realise the dark side of 'respectable' human nature; under no great temptation to crime, but daily giving way to selfishness and ill-temper, till its conduct towards those dependent on it sometimes amounts to a tyranny of which one would rather be the victim than the inflicter. [14]Each of these three characters offers a bleak portrait of "the immovable plight of the single woman without money." [15]

Fortunately in her fictional world Austen can arrange matters more happily than they generally turned out in real life. And Emma is her sunniest novel. At its conclusion—skip to the next paragraph if you don't want to know how it all turns out—Harriet's future is assured by her marriage to a "'respectable, intelligent gentleman-farmer,'" Miss Bates will be more firmly integrated into Highbury's social world through Emma's "regular, equal, kindly intercourse" and solicitude, and Jane Fairfax is rescued from the need to become a governess by her marriage to the man to whom she has long been secretly engaged. Even Emma discovers that despite her lack of financial need, her intention to remain unmarried has been subverted by the discovery that she is in love. [16]

Of course, for those facing "the immovable plight of the single woman without money" there was another possible way to earn an independent income. But it lay on the fringes of respectability, involved a substantial degree of financial risk, and offered only a modest promise of return: publish a novel.

Next time: Northanger Abbey and women writers and readers

Last time: Mansfield Park and slavery III: An estate built on "the ruin and labour of others"

Other posts in the "Six months with Jane Austen" series:

- Favorite adaptations and final thoughts

- Persuasion and Austen's sailor brothers

- Persuasion and the British Navy at war

- Mansfield Park and slavery II: Lord Mansfield and the antislavery movement

- Mansfield Park and slavery I: Fanny Price and Dido Elizabeth Belle

- Pride and Prejudice and the marriage market

- Sense and Sensibility, inheritance, and money

- The plan

Portraits by Sir Thomas Lawrence, top to bottom:

- Duchesse de Berry (detail), 1825

- Lady Wallscourt Playing Music (detail), 1825

- Mrs Siddons as Mrs Haller in 'The Stranger' (detail), c. 1796-1798

- Mary, Countess Plymouth (detail), 1817

- Jane Austen, Emma, Volume I Chapter i; Chapter 1.

- "thirty thousand pounds": Emma, I. xvi.; 16. "'declares she will never marry'": Emma, I. v.; 5. "none of the usual inducements": Emma, I. x.; 10.

- "very little intention": Emma, I. x.; 10. "of importance to no one": Jane Austen, Northanger Abbey, Lady Susan, The Watsons, and Sanditon. Oxford World's Classics, 1990, pp. 317-318.

- Emma, I. iii.; 3.

- "a parlour-boarder," "very liberal," "no settled provision": Emma, I. viii.; 8.

- Emma, I. viii.; 8.

- "moderate-sized apartment": Emma II. i.; 19. "very small way": Emma, I. iii.; 3. "barely enough": Emma, II. v.; 23.

- Emma, I. x.; 10.

- Emma, III. vii.; 43.

- Emma, II. ii.; 20.

- "Bristol—merchant": Emma, II. iv.; 22. "not at all afraid": Emma, II. xvii.; 35.

- Emma, III. viii.; 44.

- David Selwyn, "Making a living," in Edward Copeland and Juliet McMaster, eds. The Cambridge Companion to Jane Austen, Second Edition. Cambridge University Press, 2011, pp.153-154.

- Elizabeth Gaskell, The Life of Charlotte Bronte, Ch. VIII

- Edward Copeland, "Money," in Edward Copeland and Juliet McMaster, eds. The Cambridge Companion to Jane Austen. Cambridge University Press, 1997, p. 129.

- "respectable, intelligent gentleman-farmer": Emma, I. viii.; 8. "regular, equal, kindly intercourse": Emma, III. viii.; 44.