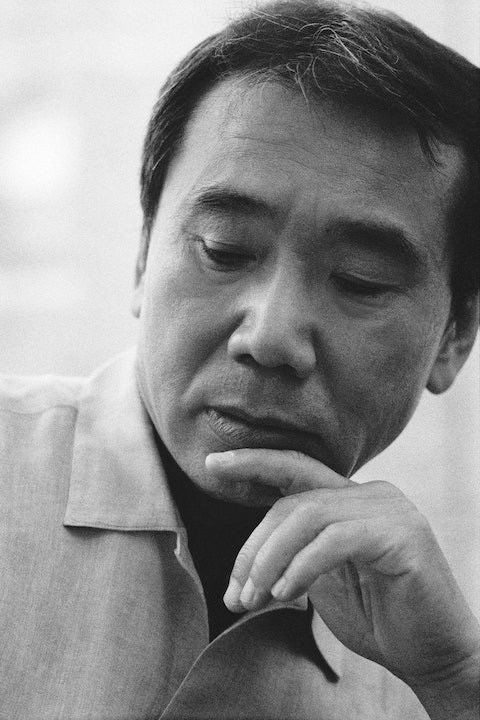

Haruki Murakami, part 2: The hard-boiled wonderland

Haruki Murakami. Photo credit: Kevin Trageser / Redux. Image source: The New Yorker

In this post series I am discussing three Haruki Murakami-related works:

- David Karashima's Who We're Reading When We're Reading Murakami (Soft Skull, 2020), an examination of the English-language publication of Murakami's books from his first novella through his international breakthrough The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle (1995/1997).

- Jay Rubin's Haruki Murakami and the Music of Words (Harvill, 2002/Vintage 2005), a survey of Murakami's life and work up through the publication of Umibe no Kafuka (Kafka on the Shore, 2002/2005).

- Ryūsuke Hamaguchi's Drive My Car (2021), the Academy-Award-winning film based on two Murakami short stories published in the collection Men Without Women (2014).

For a discussion of the Murakami novels that were published in the Kodansha English Library series for Japanese readers learning English, please see Haruki Murakami, part 1: The English Library novels.

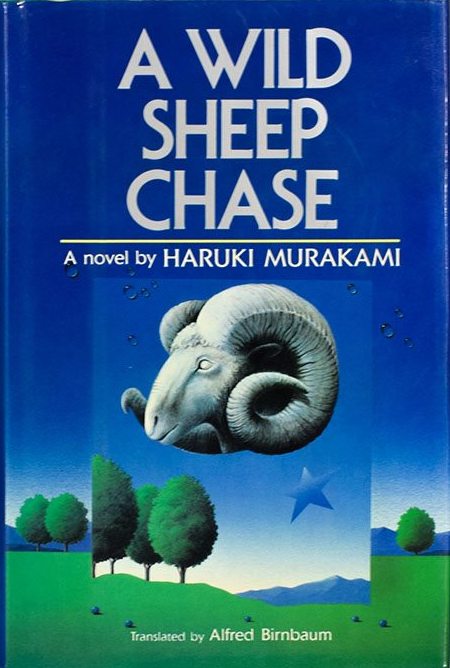

Cover design: Shigeo Okamoto. Image source: Raptis Rare Books

After translating Pinball, 1973 (1980/1985), Hear the Wind Sing (1979/1987), and Norwegian Wood (1987/1989) for the Kodansha English Library, Alfred Birnbaum was finally able to work on the novel that had originally inspired him to translate Murakami. The title A Wild Sheep Chase is not a literal translation of Murakami's original Japanese title Hitsuji o meguru bōken (which means something like "An Adventure Involving Sheep"), but instead is Birnbaum's inspiration, recalling the English expression "a wild goose chase."

This is an approach that characterizes Birnbaum's translations in general: he is more concerned with rendering Murakami's writing in a vivid way that will engage American and UK readers than with strict fidelity to the Japanese original. And with this book he was working with a new editor, Elmer Luke, who had been hired (along with several others) at Kodansha with the goal of increasing U.S. sales. A Wild Sheep Chase, Murakami's third novel, had originally been intended for the English Library series. But with Luke's backing, Kodansha decided to publish it in hardback in the U.S., where it came out in 1989.

A Wild Sheep Chase features many tropes that recur in Murakami's later books: the interaction between an alternate world and everyday reality; a laconic, whiskey-drinking protagonist who becomes enmeshed in a mystery and reluctantly takes on the role of detective; and traces of the lingering but unacknowledged traumas of World War II. I had read fiction by Ryūnosuke Akutagawa, Kōbō Abe, and Junichirō Tanizaki, but Murakami's narrative voice (at least, as rendered into English by Birnbaum) seemed more like a contemporary cross between Kurt Vonnegut and Raymond Chandler.

The plot of A Wild Sheep Chase defies easy summary; Rubin's synopsis takes a dozen pages. But here's my attempt in a few paragraphs: Five years after the action of Pinball, 1973, the protagonist Boku ("I") is 29 (Murakami's age in 1978), is divorced after four years of marriage, is running a small advertising agency, and is currently living with a girlfriend who has perfect ears. Boku's college friend, the Rat, has disappeared but has kept in touch periodically by mail. The last communication Boku received from the Rat contained a photograph of sheep and a request that he make the photo public in some way. Boku uses the photo in an ad, and shortly afterward is visited by a sinister man dressed in black. He is acting for his shadowy Boss, who has a keen interest in a particular sheep with a star-shaped mark on its back that appears in the photo.

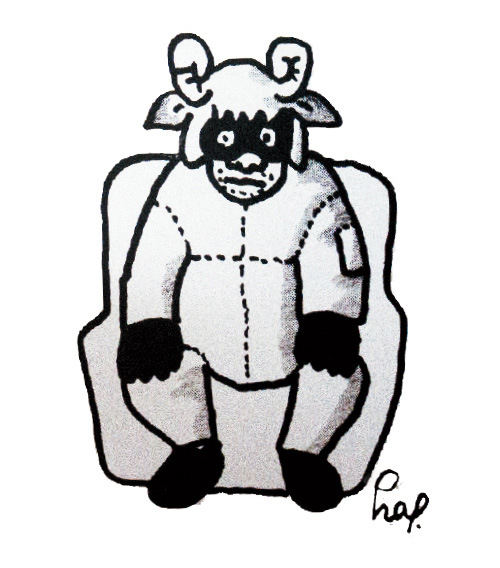

Boku and his girlfriend set off to find the Rat, a journey that takes them to the northern island of Hokkaidō. There at the girlfriend's suggestion they check into the Dolphin Hotel, where they meet the "Sheep Professor." The old man reveals that in the mid-1930s he was briefly possessed by the malevolent spirit of the sheep with the star-shaped mark; it soon moved on to other hosts. Boku finds his way to the Rat's cottage, where he encounters the "Sheep Man," who wears a self-fashioned sheepskin suit.

Illustration of the Sheep Man by Haruki Murakami, from Hitsuji o meguru bōken. Image source: Niponica: Discovering Japan

Boku decides to wait in the cottage for the Rat; the first night, while he's sleeping, his girlfriend disappears (shades of the twins in Pinball, 1973). Ultimately Boku learns what became of the Rat and the significance of the sheep with the star-shaped mark. (And, indeed, of all the sheep in Japan: they were imported as a domestic source of the wool needed to make winter uniforms for the Japanese Army's invasion of northern China; they are a legacy of Japan's violent imperialist past.)

One reason A Wild Sheep Chase seems so immediate to English-language readers is due to Birnbaum and Luke's choice to eliminate dates in the novel. It has a prelude set on a specific day in 1970: 25 November, the day that the right-wing writer Yukio Mishima committed seppuku after failing to rouse the Japanese Self-Defense Forces to revolt and restore the Emperor to power, a news story unfolding live on the soundless TV set in the bar where an indifferent Boku is having a beer. The major events of the narrative occur eight years later (the novel itself was originally published in 1982). But in Birnbaum's translation references to specific dates are omitted or obscured. As a result the novel seems to take place in the present day of the reader, rather than in a particular moment in the past.

In Haruki Murakami and the Music of Words, Murakami translator Jay Rubin suggests that in his view Birnbaum is too free in his translation of A Wild Sheep Chase. He gives as an example Birnbaum's rendering of the title of Chapter 24, "Iwashi no tanjo" (The birth of Sardine) as "One for the Kipper." (The reference is to a cat, who over the course of the chapter acquires the name Kipper, or Sardine.)

Rubin writes, "Set in 1978, the novel should not have contained—and does not in the original—this reference to the famous movie line 'Make it one for the Gipper,' which flourished during the Reagan years after 1980" (p. 189). The actual line from Knute Rockne, All American (1940) is "win just one for the Gipper." Reagan used the catchphrase (without the qualifying "just") in his 1965 autobiography, Where's the Rest of Me?, adopted "Gipper" as his nickname, and used it throughout his political career: a Time magazine article from 29 March 1976 refers to Reagan as "Gipper" three times, including in the headline. Rubin's claim that "one for the Gipper" is a phrase that could not have been known to a narrator in the late 1970s is unfounded.

And there's another connection that might have been known to Birnbaum. The day of the Army-Notre Dame football game in which coach Knute Rockne gave the "win one for the Gipper" halftime speech was 10 November 1928. Newspapers carrying previews of the game also had front-page headlines reporting Hirohito's enthronement ceremonies as the Emperor of Japan.

Front page of the Taunton (Mass.) Daily Gazette, 10 November 1928. Image source: Timothy Hughes Rare & Early Newspapers

It was under Hirohito's rule, of course, that Japan's wars of imperial conquest in Asia and the Pacific were waged. Since the star-backed sheep represents the violent, nationalistic elements that remain present but hidden in Japanese society, Birnbaum's reference to the Gipper, and thus through historical association to Hirohito's accession, seems perfectly apposite and historically resonant.

A Wild Sheep Chase received many good reviews (my initial interest in the novel must have been sparked by one) and sold a respectable 8500 copies, but it was just the beginning. Birnbaum and Luke began searching for a follow-up. Although in 1988 Murakami had written a sequel to A Wild Sheep Chase, Dansu dansu dansu (Dance Dance Dance), and Norwegian Wood had been a bestseller in both its original Japanese and its English Library editions, neither was the next novel selected. Luke thought that Norwegian Wood's coming-of-age story was "too Japanese" to be the next Murakami book English-language readers encountered. And Dansu Dansu Dansu probably would not expand his readership beyond those who had already liked A Wild Sheep Chase.

Instead Birnbaum and Luke decided on Murakami's fourth novel, Sekai no owari to Hādo-boirudo Wandārando (The End of the World and Hard-Boiled Wonderland, 1985), which was longer and, with its parallel-worlds plot, even more complex than A Wild Sheep Chase.

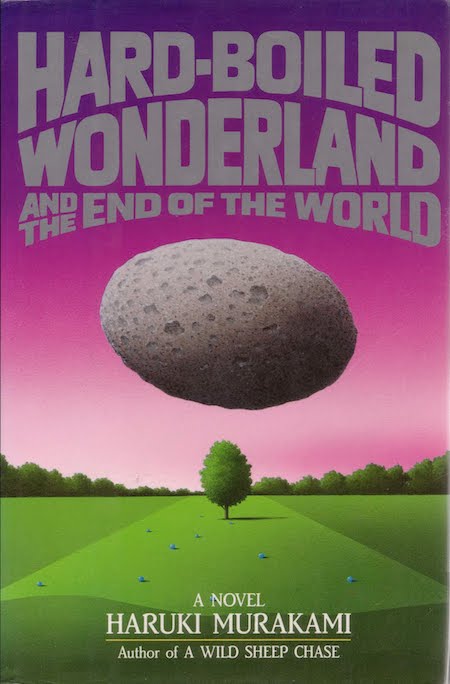

Cover design: Shigeo Okamoto. Image source: Huc & Gabet

Again the title was freely translated, this time reversing the order of the two worlds in the original (neither Birnbaum nor Luke wanted the book to be known as End of the World, which they thought was clichéd). Murakami had distinguished the two worlds of the novel in part through the first-person pronouns employed: in the Hard-Boiled Wonderland chapters, which take place in a near-future Tokyo, the narrator uses the more formal watashi; in the End of the World sections, which occur in a dreamlike (or nightmarish) walled Town, the more familiar boku. English, of course, has only one first-person pronoun, "I." Birnbaum chose to render the Hard-Boiled Wonderland chapters in the past tense, and the alternating End of the World chapters in the present tense. (As it will turn out, there is no sense of the past in the End of the World.)

In the biggest change from the Japanese original, Luke estimates that he and Birnbaum cut about a hundred pages of material, much of which relates to the 17-year-old Girl in Pink and her relentless (and graphically explicit) sexual pursuit of the 35-year-old narrator. Luke finds the Girl in Pink material "preposterous almost," and Birnbaum defends their cuts of "an embarrassing amount of unfocused extraneous material" (Karashima pp. 116, 120). Even so, the translation came in at 400 pages, a third longer than A Wild Sheep Chase.

If A Wild Sheep Chase adopted aspects of hardboiled crime novels, Hard-Boiled Wonderland additionally incorporates elements of cyberpunk and fantasy fiction. Watashi, the sardonic first-person narrator in the Hard-Boiled Wonderland, is a Calcutec: a human computer who encrypts and stores data in his brain. There is another group of human computers called the Semiotecs, who are rogue Calcutecs using their skills to steal data and sell it for profit or use it for their own ends. Semiotecs work for an organization called the Factory, which opposes the corporate System that controls Tokyo and creates and directs Calcutecs. There are hints that the Factory and the System are both parts of the same vast organization, and (like the global adversaries in Orwell's 1984) both Factory and System benefit from their perpetual war.

Watashi takes a job at a bizarre office building with a huge elevator and corridors that go on seemingly without end; this is where he meets the Girl in Pink, who is the receptionist. From his office Watashi descends a ladder to a subterranean river, the realm of the dangerous INKlings. The office is really a cover for the laboratory of the elderly Professor (grandfather of the Girl in Pink), who has set up his laboratory deep underground. Although the INKlings are hostile to humans, they are also a form of security. Their presence serves to deter anyone from stealing the Professor's research: he has found a way to record images from the subconscious.

The Professor asks the Calcutec to process his data by "shuffling," a highly restricted procedure that involves passing the data through the Calcutec's subconscious. It turns out that that the Professor used to be Chief of Research for the System. He is the one who enabled Calcutecs to shuffle data by recording their subconscious images, editing them into a semi-coherent story, and implanting them back in their brains. Watashi is the only surviving Calcutec who has undergone this procedure; his implanted story is called "The End of the World."

In a parallel narrative, we encounter the first-person narrator Boku. He has recently arrived in a walled Town, from which no one is allowed to leave. On Boku's arrival, the Town's Gatekeeper has severed his Shadow, where all his memories are stored. Shadows are left to die, along with the unicorns that absorb the final traces of the Townspeople's dreams and live outside the Town, exposed to the harsh winter. As his own individuality slowly fades, Boku plots to reunite with his Shadow and escape the Town.

As elements from one narrative gradually bleed into the other, we come to realize that the Town is Watashi's subconscious "End of the World." The data shuffling that the Professor has had the Calcutec perform will sever the connection between Watashi's conscious mind and the real world of the Hard-Boiled Wonderland. In little more than a day Watashi will be forever sealed inside his own mind, unless the Professor reverses the process. But Factory thugs, aided by INKlings, have broken into and destroyed the Professor's laboratory. . .

Published in the U.S. in 1991, Hard-Boiled Wonderland was not quite as widely or as well reviewed as A Wild Sheep Chase, and sold only about 5,000 copies in hardback. (One of those is on my shelf.) Murakami had lost some of his novelty value, in part because it had been two years since the publication of A Wild Sheep Chase, and in part because it was becoming clear that he was not alone.

In the wake of the success of A Wild Sheep Chase, Birnbaum had edited and translated a collection of recent Japanese short stories and novel excerpts with the arresting title Monkey Brain Sushi: New Tastes in Japanese Fiction. In his review of Hard-Boiled Wonderland, science-fiction writer Bruce Sterling wrote that Monkey Brain Sushi "demonstrates that there are plenty more where Murakami came from. Slangy, vivid, caustic and political, media-soaked and set on fast-forward, this 'New Fiction' crowd is fiercely intent on showing the world that Kawabata, Tanizaki and Mishima are history" (Karashima p. 123). As indeed they were; the most lately deceased of the three had died twenty years before Sterling's review was published. And of course part of the "slangy, vivid" character of the writing reflected Birnbaum's style as a translator.

Murakami was disappointed that his U.S. sales hadn't grown with Kodansha. He decided to switch agents and publishers, a change that would ultimately also mean a change in translators, and in his literary fortunes.

Next time: The transition: The Elephant Vanishes and Dance Dance Dance.

Other posts in this series:

- The English Library novels: Hear the Wind Sing (1979/1987), Pinball, 1973 (1980/1985), and Norwegian Wood (1987/1989)

- International breakthrough: The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle (1995/1997)

- Film adaptation: Ryūsuke Hamaguchi's Drive My Car (2021)

- Comics adaptation: Jean-Christophe Deveney and PMGL's Manga Stories (2023)

- More film adaptations: Burning (2018) and Norwegian Wood (2010)