African Queen: Sofonisba

The Death of Sophonisba by Giambattista Pittoni, c. 1730s. Image source: Wikimedia Commons

Sofonisba (also spelled Sophonisba), daughter of Hasdrubal, the king of Carthage, appears in Book XXX of Livy's history of Rome. Betrothed to the Eastern Numidian prince Massinissa, she is instead forced by her father to marry Siface (Syphax), the Western Numidian king with whom Hasdrubal wishes to make an anti-Roman alliance. Stung by Sofonisba's marriage to his rival, Massinissa revolts against Siface and joins forces with the Roman general Scipio. Together they defeat Hasdrubal and Siface in battle, taking as prisoners both Siface and his wife.

Massinissa is still in love with Sofonisba, and she with him. After anguished reflections on her duty to the husband she married unwillingly, Sofonisba leaves Siface and returns to her former love. However, Scipio believes that Sofonisba urged Siface to rebel against Rome, and wants to parade her in chains through its streets in a triumphal procession. Massinissa wavers. Sofonisba, rather than suffer such humiliation, begs him to procure poison for her, drains the chalice sent to her by messenger, and dies. [1]

The Death of Sophonisba, attributed to Pierre Guérin, c. 1810. Image source: The Cleveland Museum of Art

Over the centuries Sofonisba's tragedy has been the subject of paintings and plays, as well as operas by Gluck (1744), Jommelli (1746), and Maria Teresa Agnesi (ca. 1750). Even to those who are familiar with Baroque opera the last name in that series may be little known.

Maria Teresa Agnesi was born in 1720 to a wealthy merchant family in Milan, a city which was then a part of the Austrian Habsburg Empire. There were two exceptionally gifted daughters in the family: Maria Teresa in music and her older sister Maria Gaetana in mathematics and philosophy. Their father held regular gatherings in their home during which Maria Gaetana would give talks and debate with learned men, and Maria Teresa would perform. An admiring account from 1739, when Maria Teresa was 18, reports that she played harpsichord pieces by Rameau and accompanied herself as she sang arias of her own composition. [2]

Maria Teresa Agnesi, artist and date unknown. La Scala Museum. Image source: Pinterest

A decade or so later she composed La Sofonisba, an opera seria about the unhappy queen. No printed libretto survives, and so the poet is unknown. The work exists in a single copy: the presentation score that was sent to Vienna for the name-day of the Empress Maria Theresa, 15 October (also the name-day of the composer). The score is not dated, but it is likely to have been completed in the late 1740s; it is dedicated to the Holy Roman Emperor Francis I, Maria Theresa's husband, who was elevated to that office in 1745. There are no performance markings in the presentation score, but it would not have been used in an actual production (copies would have been made). However, the absence of any performance parts, printed libretto, or record of a production makes it seem unlikely that the opera was ever performed.

Title page of La Sofonisba by Maria Teresa Agnesi. Image source: Österreichische Nationalbibliothek

We might speculate that one reason for a lack of performance could be the apparently odd choice of a subject for a celebration of the Empress's name-day. After all, Sofonisba is forced to marry a man she doesn't love, is militarily defeated, held captive, and commits suicide. But Sofonisba's choice of death rather than dishonor places her in the company of other noble women from antiquity who were extolled for their courage, such as Dido and Cleopatra.

Like Dido and Cleopatra, Sofonisba ruled in North Africa. And this, along with the role's low vocal range, suggests that the opera may have been intended as a vehicle for a specific prima donna: the contralto Vittoria Tesi Tramontini, who by the late 1740s was living in Vienna.

Tesi, the daughter of an African servant at the Medici court in Florence, was known as "La Moretta," the Dark One (she was also known as "La Fiorentina"—The Florentine—and "La Tesi"). Born in 1700, she first appeared onstage in 1716. Over the course of her four-decade career she appeared in theaters throughout Italy, Austria and Germany with colleagues such as mezzo-soprano Margherita Durastanti and the castrati Senesino and Caffarelli, all three of whom sang in Handel's London opera companies. [3]

Vittoria Tesi Tramontini, caricature by Marco Ricci, c. 1720-1730. Image source: Royal Collection Trust

In Vienna, Tesi performed the title roles in Gluck's Semiramide riconosciuta (1748), Jommelli’s Achille in Sciro (in which the Greek warrior-hero Achilles is dressed throughout as a woman) and his Didone abbandonata (both 1749). Although opinions on Tesi's singing were divided, particularly late in her career, all observers praised her acting and expression.

In the early 1750s she began to retire from the stage, although in 1754 she is known to have performed in Gluck's Le cinesi, composed for the extravagant Schlosshof festival. Perhaps she came out of retirement to perform for the Empress, in whose honor the festival was held and of whom Tesi was a favorite: until the end of Tesi's life she held the honorary title of virtuosa della corte imperiale (Virtuosa of the Imperial Court) and lived in the Vienna palace of the Empress's military commander and advisor Prince Joseph Friedrich of Hildburghausen (also a noted patron of Gluck).

In her retirement Tesi became a well-regarded vocal teacher whose students included Caterina Gabrielli, who has been described as "one of the most eminent and perfect singers of her time," and who appeared with Tesi in Le cinesi, and Anna Lucia de Amicis, "one of the most acclaimed singers of the second half of the 18th century." [4] In December 1762 Tesi is known to have met the 6-year-old Wolfgang Mozart and his 11-year-old sister Nannerl during their first visit to Vienna; ten years later Mozart would create the role of Giunia in Lucio Silla for Tesi's student de Amicis.

"La bravissima Tesi," caricature by Antonio Maria Zanetti. Image source: Wikimedia Commons

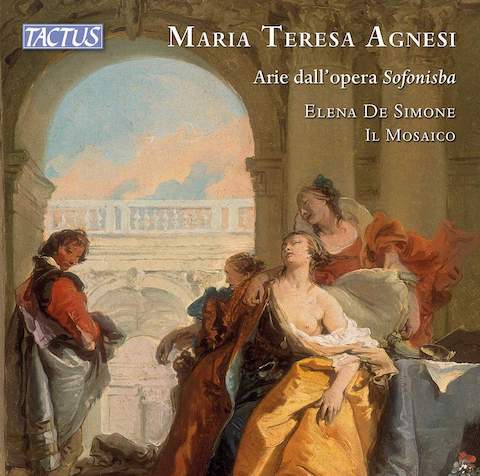

On the album Arie dall'opera Sofonisba (Tactus) the mezzo-soprano Elena De Simone, accompanied by the ensemble Il Mosaico, performs seven arias from Agnesi's Sofonisba, plus its Licenza, or celebratory epilogue in honor of Maria Theresa; De Simone also edited the performance score. As a listening experience the album is highly recommendable: De Simone has a rich, low voice that easily encompasses the wide vocal and emotional range of Sofonisba's arias, and Il Mosaico offers excellent support (and the natural trumpets used in two of the arias have a nicely pungent tone). The record would be valuable alone for showcasing the under-celebrated work of Agnesi and Tesi, but the high quality of the performances means that it will recommend itself to all lovers of Baroque opera.

Elena De Simone. Image source: MusicVoice.it

According to the liner notes by scholar Robert Kendrick, the album was designed to "reveal different affects of different roles" in the opera. In this it succeeds admirably, offering four arias sung by Sofonisba, two by her confidante (and Massinissa's sister) Elisa, also an alto role, and one by Massinissa, a soprano role probably intended to be sung by a castrato. Clearly a good deal of thought has gone into sequencing the tracks as well, with adjacent arias offering contrasting tempos or tone.

However, the arias are not presented in the order in which they appear in the opera, and so the arc of the story is obscured. For example, on the album the last aria sung by Sofonisba is track 6, "Spera Roma," a martial aria of defiance from Act II, while her "Dall' eterno felice soggiorno," the only aria included from Act III, opens the album.

CD cover of Maria Teresa Agnesi: Arie dall' opera Sofonisba, Elena De Simone, Il Mosaico. Tactus TC 720102. Image source: Presto Music

Kendrick's liner notes identify the character, act and scene of each aria and provide some contextual information, but the descriptions are not in the same order as the album tracks. No texts or translations are provided, although a helpful link is given to the digitized score held by the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, so interested listeners can follow along with the arias from Act I, Act II, and Act III.

Finally, the album is only 54 minutes long: there was certainly room to include two or three more arias and perhaps the overture. Particularly puzzling is the absence of Sofonisba's final aria before her death, "Già s’appressa il fatal momento estremo," described in the Grove Music Online entry on the composer as "particularly moving and dramatic." [2] Perhaps De Simone and Il Mosaico hoped to leave us wanting more, or perhaps they are planning a second Sofonisba volume. Either way, I'm looking forward to the results of their further explorations.

Sofonisba's first aria, "Dubbia ancor," from Act I, Scene 2:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KqP8GFTdumo

|

Dubbia ancor del mio destino |

Still doubtful of my destiny |

Update 5 March 2022: In his comment below M. Lapin has pointed to musicologist, historian and photographer Dr. Michael Lorenz's informative blog post "The Will of Vittoria Tesi Tramontini." It is a fascinating close look at the terms of her will, and provides far more details about her life than the brief accounts I used in this post. It is highly recommended, and many thanks to M. Lapin for bringing it to my attention.

Other posts about Vittoria Tesi:

- The first Black prima donna: Vittoria Tesi

- Vittori Tesi: Some notable operatic performances, 1716-1754

- Vittoria Tesi's colleagues: Rival Queens and castrati

- Why is Vittoria Tesi not better known?

- Information about the opera Sofonisba in this post derives from Robert L. Kendrick, booklet notes, Maria Teresa Agnesi: Arie dall' opera Sofonisba, Elena De Simone, Il Mosaico, Tactus TC 720102, 2021.

- Information about Maria Teresa Agnesi in this post derives from Sven Hansell and Robert L. Kendrick, "Agnesi, Maria Teresa," Grove Music Online, 25 February 2021, doi: 10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.00292

- Information about Vittoria Tesi Tramontini in this post derives from Gerhard Croll, "Tesi (Tramontini), Vittoria," Grove Music Online, 20 January 2001, doi: 10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.27735. The date of Tesi's meeting with Mozart in this article, 13 December 1762, may be erroneous: according to Otto Erich Deutsch's Mozart: A Documentary Biography (Stanford University Press, 1965), the Mozart family left Vienna for Pressburg (Bratislava) on 11 December, returning on 24 December; see p. 18.

- Gerhard Croll and Irene Brandenburg, "Gabrielli [Gabrieli], Caterina [La Cochetta]," Grove Music Online, 20 January 2001, doi: 10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.10452; Saskia Willaert, "De Amicis [De Amicis-Buonsollazzi], Anna Lucia," Grove Music Online, 31 January 2014, doi: 10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.07330