Why is Vittoria Tesi not better known?

Vittoria Tesi, probably at the Teatro San Giovanni Grisostomo in Venice during the Carnival season of 1735-36; caricature by Anton Maria Zanetti. Image source: Royal Collection Trust

Opera politics

Vittoria Tesi, the first Black or biracial prima donna, is an extraordinary and ground-breaking figure. She held the stage on equal terms with other superlative singers of her time, such as the Rival Queens Faustina Bordoni and Francesca Cuzzoni, Handel's longtime leading lady Anna Maria Strada, and the castrati Farinelli, Senesino, Carestini and Caffarelli. And yet I've been listening to Baroque opera for nearly 30 years and can't recall having heard her name before. One reason she is not as well known as her colleagues listed above and highlighted in the previous post is that, unlike every one of them, she never sang in London.

Handel came to Dresden in 1719 to recruit Senesino and other Italian singers for the Royal Academy, which would produce operas in London between 1720 and 1728. Although he saw Tesi perform in Lotti's Teofane and Giove in Argo (to whose libretti he later composed his own operas), he apparently did not extend an offer to her.

It's not known why Handel didn't attempt to engage Tesi, but a possible explanation may be opera politics. Since Senesino was the star Handel had been sent to recruit, his wishes weighed heavily in casting decisions. Soprano Maddalena Salvai was hired for the Royal Academy on Senesino's recommendation/insistence, for example, and travelled to London with Senesino and his frequent colleague, the castrato Matteo Berselli. It may be that Senesino, who was notoriously prickly, favored other singers over Tesi. [1]

Francesco Bernardi, detto il Senesino, engraved by Elisha Kirkall after Joseph Goupy, 1727. Image source: National Portrait Gallery, London

And although this is speculating about a speculation, it's possible that Senesino was motivated by professional jealousy: Tesi's vocal range was similar to Senesino's but apparently even wider. And at this early stage in her career (she was 19 and had been singing professionally for three years) she sang male as well as female roles: in Dresden she appeared both as the goddess Diana (in Giove in Argo) and as the god Mars (in Heinichen's La Gara degli Dei); she also sang the female role of Matilda, Ottone's cousin in Teofane, as well as the male role of Celso, Ascanio's confidant in Lotti's Ascanio, ovvero Gl' Odi delusi dal sangue. Senesino may have been wary of the competition.

There may also have been reasons of theatrical practicality for Handel's decision not to engage Tesi: Handel already had a long-established professional relationship with the English contralto Anastasia Robinson.

Opera economics: Handel's contraltos

Anastasia Robinson, engraved by John Faber Jr. after John Vanderbank, 1723. Image source: National Portrait Gallery, London

Robinson (then a soprano) was the singer for whom Handel had written "Eternal source of light divine" in Ode for Queen Anne's Birthday (1714), and she had sung with his opera company from 1714 to 1717. She created the role of Oriana, the heroine held captive by the sorceress Melissa, in Amadigi di Gaula (1715), and also appeared as Almirena, the heroine held captive by the sorceress Armida, in revivals of Rinaldo. She would sing with the Royal Academy from its first production, Radamisto (1720), in which she created the role of Radamisto's wife Zenobia, the heroine held captive by the tyrant Tiridate, through Giulio Cesare (1724), in which she created the role of Pompey's widow Cornelia, the heroine held captive by the tyrant Tolomeo.

Cornelia and her son Sesto's duet at the close of Act I of Giulio Cesare, "Son nata a lagrimar":

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Td_Tn9VC_G8

|

Son nata a lagrimar/ Son nato a sospirar, e il dolce mio conforto, ah, sempre piangerò. Se il fato ci tradì, sereno e lieto dì, mai più sperar potrò. |

I was born to weep/ I was born to sigh, and my sweet comfort, Alas, I will always mourn. If fate betrays us, for serene and joyful days We can never hope. |

The performers are Natalie Stutzmann (Cornelia) and Philippe Jaroussky (Sesto) accompanied by Orfeo 55 conducted by Stutzmann.

After the 1724 season Robinson secretly married Charles Mordaunt, Earl of Peterborough, and retired from the stage. This was another opportunity for Handel to engage Tesi; however, Robinson was replaced instead by the Italian contralto Anna Vincenza Dotti. Dotti was probably recruited in Venice by the impresario Owen Swiney (also spelled Swiny), who was acting as an agent for the Royal Academy. [2]

In 1724, Tesi was geographically remote from Venice: after a Carnival season in Milan and a Spring (post-Easter) season in Parma with Faustina, she travelled to Naples. She performed there through the 1726 Carnival season, often in prima donna or title roles. Even if Swiney had been in contact with Tesi (and there is no evidence in Swiney's letters to Academy subscriber Charles Lennox, the Duke of Richmond, to suggest that he was), the Academy probably couldn't have afforded her in addition to the salaries that were being paid to Senesino, Cuzzoni, and later Faustina (who signed a contract in 1725).

I was unable to find a source specifying Dotti's salary; my guess is that it was near or below the £500 that was paid to Robinson. When Dotti replaced Robinson, Handel reduced the prominence of her characters relative to Robinson's as indicated by the number of arias per opera. There is also an uncomplimentary first-hand report by Lady Bristol of Dotti's debut in Handel's Tamerlano on 31 October 1724: ". . .the [new] woman [Dotti] is so great a joke that there was more laughing at her than at a farce, but her opinion of her self gets the better of that." [3]

After the Royal Academy's final season in 1727-28, it was left heavily in debt and unable to continue. The directors agreed to turn the production of operas over to the impresario John Heidegger and Handel for the next five years, an arrangement that has become known as the Second Academy. Once again Handel needed to find singers, and in the winter of 1729 he travelled to Italy on a recruiting trip. He arrived in Venice in February and over the next three months visited Bologna, Siena, Rome, and Naples. However, he evidently didn't see Tesi perform again: in February and early March of that year Tesi was singing in Milan. By mid-May Handel had engaged a full company, including the castrato Antonio Bernacchi (Tesi's former teacher), the soprano Anna Maria Strada, and the contralto Antonia Merighi; by late May or early June he'd left Italy on his return journey to England.

Portrait of Handel by Balthasar Denner, ca. 1727. Image: Wikimedia Commons

A July 1729 entry in the diary of the London musician John Grano gives us a sense of one of Handel's major goals for the upcoming season: "Met Mr Smith the Opera Copyest in the Park, who told me the Performers Mr Handel Engag’d in Italy whe[re] very good and Cheap." John Christopher Smith was Handel's music copyist and friend; his information was likely from Handel himself. As an example of what "cheap" meant in the context of opera singers, Bernacchi was paid £1200 for the season, a savings of £300 over Senesino's salary; Strada was paid £600, a savings of £900 over Francesca Cuzzoni or Faustina Bordoni; and Antonia Merighi, apparently an improvement over Anna Dotti, was paid £800. [4]

Tesi would not have been "cheap." It can be hard to trace the compensation of singers; payment records don't always exist, and in addition to salaries, singers often received proceeds from (contractually specified) benefit performances, not to mention gifts from enthusiastic patrons. But we can estimate the fee Tesi would have required from Handel from information we have about her salary relative to that for the castrato Carestini.

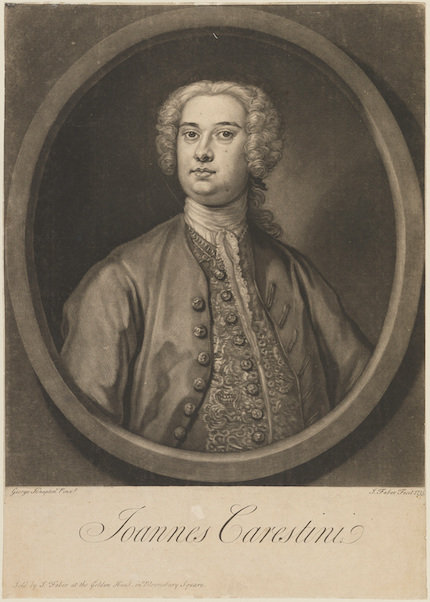

Joannes [Giovanni] Carestini, engraved by John Faber Jr. after George Knapton, 1735. Image source: National Portrait Gallery, London

In the summer of 1730 Handel was attempting to engage a castrato to replace Bernacchi, who evidently had not pleased London audiences. Owen Swiney wrote on 18 July, "Senesino or Carestini are desired at 1200 G[uinea]s each, if they are to be had." In 1730 it was Senesino who finally agreed to terms, after negotiating his fee upwards. But a few years later, after Senesino deserted Handel for the rival Opera of the Nobility, Carestini did join Handel's company. He was engaged for the 1733-34 and 1734-35 seasons, probably for something close to the 1200 guineas per season that had been suggested in 1730. [5]

Carestini's aria "Mi lusinga il dolce affetto" from Alcina (1735):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yD1Z-wwsjPE

|

Mi lusinga il dolce affetto con l'aspetto del mio bene. Pur chi sà? temer conviene, che m'inganni amando ancor. Ma se quella fosse mai che adorai, e l'abbandono; infedel, ingrato io sono, son crudele e traditor. |

Sweet passion tempts me at the appearance of my beloved. But who knows? I fear that by loving once more, I deceive myself. But should it ever come to pass that I adore and then abandon her, I would be unfaithful, ungrateful and a cruel traitor. |

The singer is Philippe Jaroussky (Ruggiero) accompanied by Le Concert d'Astrée conducted by Emmanuelle Haïm.

But both Handel's company and the Opera of the Nobility struggled, and after the close of the 1734-35 season Carestini returned to Italy. Benedetto Croce reports that for the 1736-37 season at Teatro di San Bartolomeo in Naples, Carestini was engaged by impresario Angelo Carasale for 800 doppie (double ducats). For the same season at the same theater Tesi accepted 700 doppie. If 800 doppie are roughly equivalent to the 1200 guineas that Handel offered Carestini for a London season, Tesi's salary of 700 doppie would be equivalent to 1050 guineas, or £1100 pounds. If this was her going rate, it is a fee that it's doubtful Handel would have been willing to pay a female singer in her vocal range. But Croce drops an intriguing hint: Tesi's acceptance of Carasale's offer of 700 doppie for the 1736-37 season in Naples, he wrote, meant "breaking off her negotiations with London." [6]

Could Tesi have been in contact with Handel or his agents in Italy after all? It's certainly possible, but given Handel's financial constraints it seems more likely that if any negotiations were taking place they were with the rival Opera of the Nobility, where her frequent stage partner Farinelli was the primo uomo. With his departure at the end of the 1737 season, the Opera of the Nobility collapsed. In any event, Tesi was never engaged by either London company, nor does any entry for her appear in the index to the three-volume George Frideric Handel: Collected Documents. [7]

Handel's London operas were thoroughly commented on at the time and have been the focus of great musical and historical interest over the past 150 years. As a result there has been extensive scholarly discussion of many of Handel's singers; since Tesi was never one of them, she is absent from that conversation.

Ars Minerva's Astianatte

Vittoria Tesi deserves to be much better known. And Céline Ricci's Ars Minerva, whose mission is to bring Baroque operas back to life, will do its part to help redress Tesi's relative neglect with their next production, scheduled for October 2022 at ODC Theater: Leonardo Vinci's Astianatte (Astyanax, 1725).

Ars Minerva Artistic Director Céline Ricci. Photo: Martin Lacey Photography. Image source: sfgate.com

Antonio Salvi's libretto for Astianatte is based on Racine's tragedy Andromaque (1688). In the opera, Andromaca (Andromache), widow of the Trojan warrior Hector, is held captive by Pirro (Pyrrhus). Pirro is the son of the Greek hero Achilles, who killed Hector in battle; although Pirro is betrothed to Ermione (Hermione), daughter of the Spartan King Menelaus and Helen, he has fallen in love with Andromaca. Andromaca, though, rejects Pirro: she is determined to honor Hector's memory and protect their son Astianatte. When Menelaus' brother Agamemnon sends his son Oreste (Orestes), former lover of Ermione, to Pirro with an an ultimatum—kill Astianatte or the Greeks will declare war—matters are brought to a crisis.

The original Naples production of Astianatte had a starry cast: Farinelli sang Oreste, with Anna Maria Strada as Erminone. And those were the secondary roles: in the main roles the opera featured Vittoria Tesi as Andromaca and contralto Diana Vico as Pirro. The inclusion of two contraltos in the cast may seem unusual, but Tesi and Vico appeared together in at least 11 operas in Bologna, Naples and Milan between 1721 and 1729.

Vico had sung in London with Handel's company at the King's Theatre from 1714 through 1716. She created the role of Dardano, Amadigi's rival for the love of Anastasia Robinson's Oriana, in the first production of Amadigi di Gaula (1715), and also performed the role of Rinaldo, the lover of Anastasia Robinson's Almirena, in the 1714-15 revival of Rinaldo.

Diana Vico in male costume, possibly as Quintus Fabius in Lucio Papiro dittatore at Teatro San Giovanni Grisostomo, Venice, 1720. Caricature by Marco Ricci, c. 1720-1730. Image source: Royal Collection Trust

Vico frequently performed male roles; for example, all of the operas she sang in London, and 10 of the 11 operas in which she appeared with Tesi, featured Vico in a so-called trouser role. Pirro's aria "Ti calpesto o crudo amore" from Astianatte, Act I, addressed to Oreste:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9DWiVpqWyhw

| Ti calpesto, o crudo amore, Hò già spento il vile ardore, Sol trionfi onore in me. E tu vanne ai Greco lido, E di pur, che Pirro è fido Nè mancò giammai di fè. | I crush you, cruel love, After extinguishing an unworthy passion, Only honor triumphs in me. And you journey now to the Greek shore And tell them that Pyrrhus is faithful Nor did he ever waver. |

The singer is Sonia Prina accompanied by Armonia Atenea conducted by George Petrou.

Ars Minerva has produced a superlative series of Baroque operas in their modern premières. I'm very much looking forward to what Ricci, her design team and her musical collaborators will offer audiences this fall. For more information about Astianatte and Ars Minerva's other projects, visit the Ars Minerva website.

Other posts on Vittoria Tesi:

- African Queen: Sofonisba

- The first Black prima donna: Vittoria Tesi

- Vittori Tesi: Some notable operatic performances, 1716-1754

- Vittoria Tesi's colleagues: Rival Queens and castrati

Update 29 May 2022: Letters sent from Vittoria Tesi to Enea Silvio Piccolomini in the summer of 1736 provide more details about her negotiations to appear in London for the coming season. On 7 July Tesi writes, "Sappiate ch'è arrivato in Napoli uno cavagliere inghilese con ordine da quella Accademia di vedere d'accordarmi, sottoscrivendo trenta dei maggiori milordi, se io vado in Inghilterra." [Know that an English gentleman arrived in Naples with orders from their Academy to try to reach an agreement, subscribing thirty of the major milords if I go to England.] And on 10 July she reports: ". . .che purtroppo mi veggo in stato, di disperazione accanto di questi Inglesi, che pretendono ch'io sia impegnata tutte le volte che mi accordano quel c'ho cercato. Ed é di millecinquecento ghinee e una recita di benefizio a mia elezione." [. . .unfortunately I see myself in state of desperation beside these English, that pretend that I am engaged every time they agree to my wishes. And it's 1,500 guineas and a benefit recital of my choosing.] [8]

Unfortunately Tesi never names the agent, which might enable us to determine with which of London's two opera companies she was negotiating. Her designation of the source of the offer as "the Academy" does not provide strong evidence either way, in my view. The (first) Royal Academy had ceased producing opera at the end of the 1727-28 season. The Second Academy—the assumption of the five years remaining on the Royal Academy's lease of the King's Theater in the Haymarket by Heidegger and Handel—had ended after the 1733-34 season. Neither company was properly the Royal Academy at this point, and since many of the Opera of the Nobility subscribers had been Royal Academy subscribers, the term "Academy" might have been loosely applied to either. That Tesi's figure of 1500 guineas seems to have been accepted by the English agent makes it more likely that he represented the Opera of the Nobility.

- See Melania Bucciarelli, "Senesino's negotiations with the Royal Academy of Music: Further insight into the Riva-Bernardi correspondence and the role of singers in the practice of eighteenth-century opera," Cambridge Opera Journal, Vol. 27, No. 3, 2015, pp. 189-213.

- Swiney was, to put it mildly, a colorful character. As manager of the Queen's Theater in London he had produced Handel's Il Pastor Fido (1712) and Teseo (1713). Neither was a runaway success; Francis Coleman's Opera Register noted of Il Pastor Fido, "Ye Habits were old, and Ye Opera short." For Teseo, Coleman wrote, "all Ye Habits new and richer than ye former with 4 New Scenes, and other Decorations and Machines." But new costumes, scenery and machines were expensive, and the opera was not such a hit that it was able to recover its production costs. Facing mounting debts, after Teseo's second performance Swiney absconded with the box office receipts and fled. Coleman reported, "Mr. Swiny Brakes & runs away & leaves ye Singers unpaid ye Scenes & Habits also unpaid for. The Singers were in Some confusion but at last concluded to go on with ye operas on their own accounts, & divide ye Gain among them." But after 11 more performances, audiences had fallen off considerably, and Teseo closed. Swiney seems to have paid back the impresario Vanbrugh by the end of May, and Handel apparently held no grudge. (Coleman quoted in Jane Glover, Handel in London: The Making of a Genius, Pegasus Books, 2018, pp. 45-46.)

- Robinson's salary and Lady Bristol quote about Dotti's Tamerlano performance from Elizabeth Gibson, The Royal Acaemy of Music 1719-1728: The Institution and its Directors, Garland Publishing, 1989, pp. 144, 212. Swiney's letters to the Duke of Richmond in Gibson, Appendix C, pp. 348-382.

- John Grano, Handel’s Trumpeter: The Diary of John Grano, ed. John Ginger, Pendragon Press, 1998, p. 284. Quoted in Ilias Chrissochoidis, Handel Reference Database 1729, accessed 17 May 2022: https://web.stanford.edu/~ichriss/HRD/1729.htm. Salaries of Second Academy singers from Elizabeth Gibson, "Owen Swiney and the Italian Opera in London," The Musical Times, 1984, Vol. 125, No. 1692, pp. 82-86. https://www.jstor.org/stable/964192

- Swiney's letter quoted in Ilias Chrissochoidis, Handel Reference Database 1730, accessed 17 May 2022: http://web.stanford.edu/~ichriss/HRD/1730.htm.

- Benedetto Croce, I teatri di Napoli, secolo XV-XVIII, L. Pierro, 1891, p. 311. https://archive.org/details/iteatridinapolis00croc/page/310/mode/2up

- Donald Burrows, Helen Coffey, John Greenacombe, Anthony Hicks, editors. George Frideric Handel: Collected documents. Cambridge, 2014; 3 vols. If Tesi was negotiating with the Opera of the Nobility, one possibility for the identity of their agent in Italy is Owen Swiney (see Gibson, The Royal Academy of Music 1719-1728, p. 353).

- Quotations from Benedetto Croce, ed. Un prelato e una cantate del secolo decimottavo: Enea Silvio Piccolomini e Vittoria Tesi: Lettere d'amore, Gius. Laterza & figli, 1946, pp. 59, 62. Translations (and any translation errors) are mine.

No comments :

Post a Comment