Favorites of 2023: Books - Our year of Agatha Christie

Image source: Simon & Schuster

For my partner's birthday last year I bought her Lucy Worsley's biography of Agatha Christie (Pegasus Crime, 2022)—more because of the biography's author (delightful star of multiple BBC history shows) than its subject. Of course, I knew Agatha Christie as the most popular British author since Shakespeare (sales of over a billion books in English alone, and another billion or so in translation), and also the writer of the longest-running play in London theatre history, The Mousetrap (1952 and counting; when we were in London this spring we saw performance number 29,146).

And, of course, like (almost) everyone I had read a few of Agatha Christie's mysteries when I was a teenager: The Murder of Roger Ackroyd (1926), recommended to me by my mother and still my favorite of Christie's novels (in 2013 it was named by the British Crime Writers' Association as the best crime novel ever written); her first novel, The Mysterious Affair at Styles (1920), which introduces a Belgian detective named Hercule Poirot; And Then There Were None (to give it its U.S. title, 1939), in which a group of weekend guests invited to a remote island estate are murdered one by one; and the short story "The Witness for the Prosecution" (1925), later adapted by Christie into a play that became the basis of writer-director Billy Wilder's 1957 movie. [1]

Cover illustration by Ellen Edwards of the first UK edition of The Murder of Roger Ackroyd. Image source: El Blog de la BLO

Inspired by Worsley's biography, and after reading The Murder of Roger Ackroyd at my recommendation, my partner embarked on a quest to read, in order of publication, all 33 novels and 51 short stories in which Hercule Poirot appears. And after a brief and pointless struggle with myself—I had last read a Christie novel many years ago, and I wondered whether I would find enjoyment in them so many years later—I began reading them along with her. Together with our trip to London, during which we saw both The Mousetrap and Witness for the Prosecution, this reading project turned 2023 into our year of Agatha Christie.

My (quickly overcome) hesitations about Christie's novels were based on my preference, which you may already have discerned in this blog, for lengthy 18th- and 19th-century novels filled with memorable characters and their richly detailed interior lives. Critic John Lanchester points out that Christie's novels operate quite differently; her prose can resemble Hemingway's in its spareness and efficiency.

Edmund Wilson wrote of Christie's novels in his essay "Who Cares Who Killed Roger Ackroyd?":

. . .you cannot become interested in the characters, because they never can be allowed an existence of their own even in a flat two dimensions but have always to be contrived so that they can seem either reliable or sinister, depending on which quarter, at the moment, is to be baited for the reader's suspicion. . .she has to provide herself with puppets who will be good for three stages of suspense: you must first wonder who is going to be murdered, you must then wonder who is committing the murders, and you must finally be unable to foresee which of two men the heroine will marry. [2]

This is unfair. Christie was a keen observer, and could limn a character's essential attributes in a few lines. However, it is true that the most fully realized character in the Poirot novels is, of course, Poirot himself. Over the course of thirty-odd novels the "odd little man" with the egg-shaped head, the well-tended moustaches, the "green flash" in his eyes when he spots a clue, the impeccably-tailored suits and ever-present patent leather shoes becomes more than a collection of vivid idiosyncrasies and develops into a rather endearing presence.

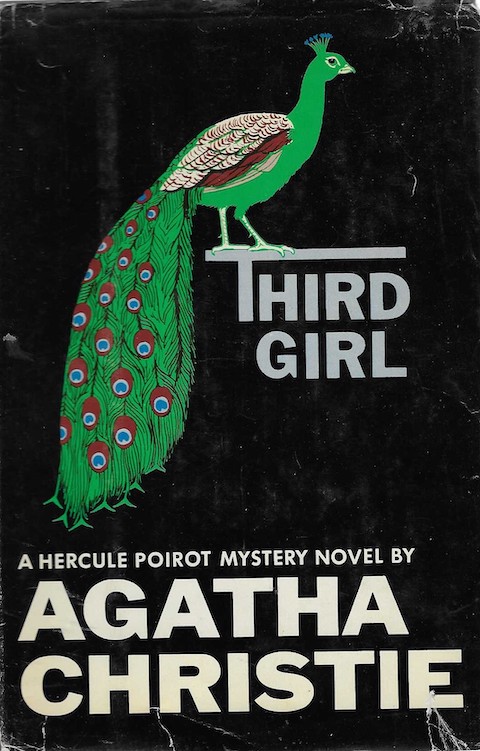

Christie herself came to regret creating Poirot, or rather, inspiring an insatiable desire in readers for new mysteries featuring him. In the novel Third Girl (1966), the mystery writer Ariadne Oliver (who is both a comic figure and an occasional stand-in for Christie herself) bewails a similar success with her fictional Finnish detective: "'. . .people say things to me—you know—how much they like my books. . .And they say how much they love my awful detective Sven Hjerson. If they knew how I hated him! But my publisher always says I'm not to say so.'" The person to whom she directs these complaints is none other than Poirot himself. [3]

Image source: AbeBooks

There are a few other irregularly recurring characters in the Poirot novels, of which the most significant is Poirot's Watson-like companion and narrator, Captain Hastings, who appears in eight novels (Ariadne Oliver appears in six). It's true that Christie's characters can sometimes fall into types. Her books are peopled with ingénues who—especially when they are pretty, auburn-haired, and catch Hastings' eye—are sometimes not as innocent as they seem; older women, who are often unpleasant and not infrequently the murder victim; and actors and actresses who are always vain, never trustworthy, and frequently mixed up in the murder. (Christie, who adapted her own work for the theatre as early as 1930, must have had some disillusioning offstage experiences.)

But it has been argued, by Lanchester for one, that Christie did not focus her energies on creating memorable characters (her detective and a few others excepted), but instead on the mystery genre's formal challenges. Christie displays almost unflagging ingenuity in handling a set of self-imposed rules that are as constraining as those of any Oulipian novel. Indeed, much of the pleasure of reading Christie is seeing how she will take familiar mystery-novel elements (some of which she herself originated) and give them an unexpected twist.

A typical Poirot mystery takes place in a tightly bounded space among a small group of people, most of whom will turn out to have both a motive and the opportunity to murder the victim. In The Mysterious Affair at Styles, the space is a country manor, a setting that will reappear in different guises in (to name a few) The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, The Peril at End House (1932), Three Act Tragedy (1935), Dumb Witness (1937), The Hollow (1946), and Dead Man's Folly (1956). In Evil Under the Sun (1941), the murders take place among an isolated group of people on an island. In Cat Among the Pigeons (1959), a murder takes place at a girls' boarding school; in Hickory Dickory Dock (1955), in a student boarding house. As the titles suggest, The Mystery of the Blue Train (1928) and Murder on the Orient Express (1934) take place onboard trains; Death in the Clouds (1935) on a passenger plane in flight; and Death on the Nile (1937) on a riverboat in transit. In Murder in Mesopotamia (1936) and Appointment with Death (1938), the murders occur on archaeological digs; Christie met her second husband, Max Mallowan, on a dig in Iraq and accompanied him on later expeditions.

Image source: The Paperback Palette

The victims are eclectic, but their deaths (at least those of the primary targets) are rarely crimes of impulse: they are meticulously planned by the killers, even if they don't reckon with the "little grey cells" of Poirot. Christie's favorite murder weapon is poison—as a young woman she had volunteered as a nurse in WWI and had learned about them during her work in a dispensary—but sometimes cruder methods are used: knives, guns, bludgeoning, strangulation, a strategic shove from a high place. As Lanchester writes,

Christie’s great talent for fictional murder is to do with her understanding of, and complete belief in, human malignity. She knew that people could hate each other, and act on their hate. Her plots are complicated, designedly so, and the backstories and red herrings involved are often ornate, but in the end, the reason one person murders another in her work comes down to avarice and/or hate. [4]

There are many clues, only some of which are significant, and victims who are not always what they seem. Suicides are made to look like murders, murders like suicides, identities are concealed, and alibis are not as solid as they first appear. It's like a puzzle or a game, and she ensures that you can almost never guess the outcome before Poirot gathers all the suspects into another bounded space (generally a parlor) to review the case and name the murderer.

In her New Yorker article "Queen of Crime," Joan Acocella itemizes the strategies Christie uses to keep us guessing. Among them are the red herring (a clue that seems significant but which, after reading a few Christie novels, we learn is too obvious to actually be important), the double bluff (where a clue that seems to be a red herring turns out to point to the real murderer), and the triple bluff (where a clue that seems at first to be a red herring, then to point to the real murderer, turns out to be a red herring after all).

But in many of Christie's mysteries, the identity of the killer is unguessable. As Acocella notes,

. . .in truth, the guessing that we are asked to do is almost fruitless, because the solution to the mystery typically involves a fantastic amount of background material that we're not privy to until the end of the book, when the detective shares it with us. Christie's novels crawl with impostors. . .The investigator digs up this material but doesn't tell anyone till the end. [5]

I wouldn't say that such solutions are necessarily typical, but they (or other solutions that rely on information that Poirot only reveals at the last moment) are rather frequent. This would seem to be a violation of the first rule of detective stories, at least as formulated by mystery writer S.S. Van Dine, which is that the reader should be supplied with all the clues necessary to solve the murder along with the detective. Poirot's ratiocinations in Murder On the Orient Express so infuriated Raymond Chandler that he snarled, "Only a halfwit could guess it." [6]

"Plan of the Calais Coach" from Murder on the Calais Coach [Murder on the Orient Express], Pocket Books, 1965. Image source: The Paperback Palette

But Christie's plots are often so intriguing and unexpected that their very intricacy and unlikelihood becomes a source of pleasure. When they fail, which is not often, they can seem overly contrived (I would nominate Death in the Clouds in that category, although it's intriguing as a mystery set in a plane at the dawn of commercial aviation). When they succeed, which is most of the time, they delight us in spite of their "unfairness." And every so often Christie provides just enough information to enable us to solve the mystery, if only we were alert and clever enough. We aren't.

Posts in this series:

- Favorites of 2023: Our year of Byron

- Favorites of 2023: Our year of Agatha Christie

- Favorites of 2023: Movies and television

- Favorites of 2023: Our year of Alec Guinness

- Favorites of 2023: Music

- Favorites of 2023: Our year of French Baroque Opera

- A word about spoilers: since the unexpected twist is such a major part of the pleasure of Christie's mysteries, if you're planning to read her I recommend trying to avoid too much knowledge about her plots. Unfortunately, many articles and TV programs can't resist showing how ingenious she was by revealing the intricacies of her murder plots. Culprits include her Wikipedia pages; Joan Acocella's, John Lanchester's, and Edmund Wilson's essays quoted in this post; and even Lucy Worsley's three-hour BBC TV series on Agatha Christie's life and work being broadcast on P.B.S. right now. These revelations are damaging to the enjoyment of all of her books, but particularly The Murder of Roger Ackroyd. I recommend approaching her work, as it were, without a clue.

- Quoted in Lanchester, "The Case of Agatha Christie." London Review of Books, Vol. 40 No. 24, 20 December 2018. https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v40/n24/john-lanchester/the-case-of-agatha-christie (warning: this link is included for scholarly completeness, but it leads to spoilers)

- Agatha Christie, Third Girl, HarperCollins, 1967, pp. 15-16. In another novel (Hickory Dickory Dock?), Ariadne Oliver fantasizes about appearing as a character in one of her own novels and killing off her detective.

- Quoted in Lanchester, "The Case of Agatha Christie." I would add another primal emotion, fear, to Lanchester's list of motives.

- Joan Acocella, "Queen of Crime: How Agatha Christie created the modern murder mystery," The New Yorker, 16 & 23 August 2010. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2010/08/16/queen-of-crime (warning: this link is included for scholarly completeness, but it leads to spoilers)

- Raymond Chandler, "The Simple Art of Murder," in Howard Haycraft, ed., The Art of the Mystery Story, Simon and Schuster, 1946. http://www.en.utexas.edu/amlit/amlitprivate/scans/chandlerart.html (warning: this link is included for scholarly completeness, but it leads to spoilers). In this essay Chandler calls S.S. Van Dine's detective Philo Vance "probably the most asinine character in detective fiction."

No comments :

Post a Comment