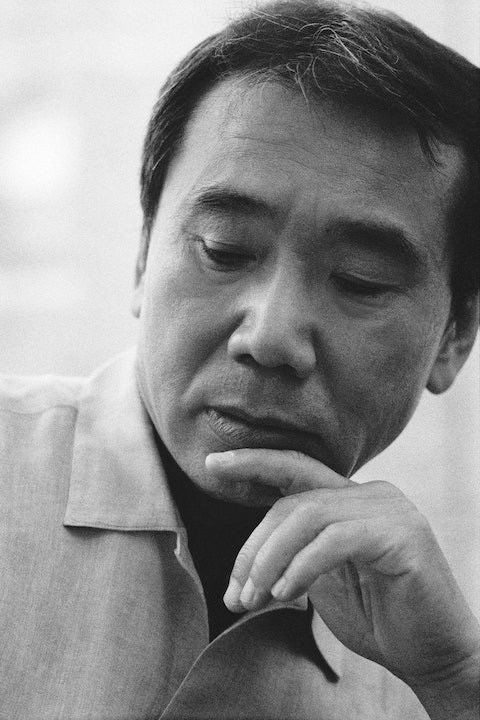

Haruki Murakami, part 1: The English Library novels

Haruki Murakami. Photo credit: Kevin Trageser / Redux. Image source: The New Yorker

Haruki Murakami was the bestselling author of six novels in Japan before any of his books were published outside of that country. But less than a decade after the U.S. publication of his third novel Hitsuji o meguru bōken as A Wild Sheep Chase in 1989, Murakami had become an international phenomenon. Today he is by far the best-known contemporary Japanese writer; his books are instant bestsellers but also receive serious critical attention. He has been a member of the visiting faculty of Princeton and Harvard, has given a lecture series at UC Berkeley, and has received an honorary degree from Yale. There is even a library dedicated to Murakami at his alma mater Waseda University.

Waseda International House of Literature (The Haruki Murakami Library). Image source: Niponica: Discovering Japan

In this post series I'll be discussing three Murakami-related works:

- David Karashima's Who We're Reading When We're Reading Murakami (Soft Skull, 2020), an examination of the English-language publication of Murakami's books from his first novella through his international breakthrough The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle (1995/1997).

- Jay Rubin's Haruki Murakami and the Music of Words (Harvill, 2002/Vintage 2005), a survey of Murakami's life and work up through the publication of Umibe no Kafuka (Kafka on the Shore, 2002/2005).

- Ryūsuke Hamaguchi's Drive My Car (2021), the Academy-Award-winning film based on two Murakami short stories published in the collection Men Without Women (2014).

David Karashima's Who We're Reading When We're Reading Murakami begins with the reason English-language readers know Murakami today: translator Alfred Birnbaum. Birnbaum had first encountered Murakami's writing in the early 1980s while working as a translator for Japanese art and design books published by Kodansha International. After a friend urged him to read a short story collection by Murakami, Birnbaum translated several of the stories on spec. During a meeting with a Kodansha editor in the spring of 1984 Birnbaum brought out his translation of the story "Nyū Yōku tankō no higeki" ("New York Mining Disaster"), and expressed interest in translating Murakami's most recent novel Hitsuji o meguru bōken, which had won the Kodansha-associated Noma New Writer's Prize in 1982 and had become a bestseller.

Instead he was given Murakami's first two short novels, Kaze no uta o kike (Listen to the Wind's Song), published in 1979, and 1973-nen no pinbōru (1973 Pinball), published in 1980. Murakami called these his "kitchen table novels," because he wrote them at his kitchen table in his off hours from running the bar he owned with his wife. [1]

Birnbaum translated the second book first, and at the suggestion of editor Jules Young titled it Pinball, 1973. In 1985 Birnbaum's translation was published in the paperback Kodansha English Library, a series published only in Japan and intended for Japanese readers who were learning English. (Each volume contained an English-Japanese glossary at the back.)

Cover illustration: Maki Sasaki. Image source: Book Dragon

Pinball, 1973 alternates between the stories of the nameless narrator (Jay Rubin calls him "Boku," after one of the Japanese words for "I") and a college friend nicknamed the Rat, who is trying to become a writer. Both men are in their mid-20s and somewhat adrift.

The Rat spends most of his time at J's Bar in Kobe. He's trying to work up the courage to leave a woman he's become involved with, because their relationship is apparently a barrier to his writing ambitions. (A reader may imagine that spending hours drinking in a bar every day instead of writing might be a greater barrier to getting anything done.) One day the Rat simply decides never to call the woman again, and leaves town for destinations unknown. [2]

Boku is living in Tokyo with cute twins whom he can only identify by their numbered sweatshirts (208 and 209). He embarks on a quest to find an unusual pinball machine that he used to play at a Tokyo arcade that closed down three years previously. Once Boku's quest reaches its end with a surreal encounter in an eerie pinball machine warehouse, the twins leave. Either obstacles and distractions, or muses, guides and healers for his male protagonists: early on Murakami set out the limited roles available to many of his women characters.

He also introduced some of the elements that would become recurring tropes in his fiction. On the first page we read that people tell the narrator stories "as if they were tossing rocks down a dry well"; the image of a well will recur in the later novels A Wild Sheep Chase and Norwegian Wood, and the protagonist will spend much of The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle at the bottom of a dry well. Also featured is the narrator's obsession with ears: in this novel, every evening after his bath the twins would "sit one on each side of me and simultaneously clean both my ears. The two of them were positively great at cleaning ears." If this sounds vaguely sexual, that suspicion will be borne out in his later books.

Pinball, 1973 also displayed Murakami's tendency to present banalities or truisms as insights:

". . . .if a person would just make an effort, there's something to be learned from everything. From even the most ordinary, commonplace things, there's always something you can learn." (p. 96)

The past and the present, we might say, "go like this." The future is a "maybe." Yet when we look back on the darkness that obscures the path that brought us this far, we only come up with another indefinite "maybe." The only thing we perceive with any clarity is the present moment, and even that just passes by. (p. 177)

Pinball, 1973 went on to multiple printings: my copy purchased in the early 1990s is the eighth. On the strength of its success Birnbaum published two more Murakami translations in the English Library: Kaze no uta o kike as Hear the Wind Sing in 1987, and the multimillion-selling blockbuster Noruwei no mori (1987), Murakami's fifth novel, as Norwegian Wood in 1989.

Cover illustration: Maki Sasaki. Image source: Abebooks.co.uk

The second novel of Murakami's to be translated into English was the first work of fiction he wrote. The novel is about the unnamed narrator's struggles to write the very book we are reading. The narrator (again, following Rubin, we'll call him Boku) looks back from 1979 on his friendship a decade previously with his college buddy the Rat. Although the Rat has ambitions to be a writer, he spends most of his time drinking beer with Boku in J's Bar. Both of them attend university in Tokyo, and are home in Kobe for the summer. The novel is set in August 1970, three years before the action of Pinball, 1973, and just months after the militant Japanese student protest movement was violently suppressed by the police. Boku has a broken tooth sustained in a police confrontation, but both he and the Rat have become disillusioned with political action, or, really, any kind of action at all.

In Haruki Murakami and the Music of Words, Rubin offers a revised translation of the first chapter of Hear the Wing Sing. [3] Comparing Birnbaum's and Rubin's translations points up some characteristic differences in their approaches. In the following passage I've placed Rubin's revisions in parentheses following Birnbaum's version:

". . .when it came to getting something into writing, I was always overcome with despair. The range of my ability was just too limited. Even if I could write, say, about elephants (an elephant), I probably couldn't have written a thing about elephant trainers (the elephant's keeper). So it went (That kind of thing).

For eight years I was caught in (went on wrestling with) that dilemma—and eight years is a long time. . .Now I think I'm ready to talk (Now I'm ready to tell). . .Still, it's awfully hard to tell things honestly. The more honest I try to be, the more the right words recede into the distance (sink into the darkness).

I don't mean to rationalize (I'm not making excuses), but at least this writing is my present best (the best I can do for now). There's nothing more to say. And yet I find myself thinking that if everything goes well, sometime way ahead, years, maybe decades, (even decades) from now, I might discover at last that these efforts have been my salvation (discover myself saved). Then lo, at that point, the elephants will return to the plains and I will set forth a vision in words more beautiful (And then, at that time, the elephant will return to the plain, and I shall begin to tell the tale of the world in words more beautiful than these). (Hear the Wing Sing, pp. 5-6|Rubin, pp. 41-42) [4]

I don't read Japanese, so I can't judge these translations by their fidelity to the original. But I do have some thoughts about tone.

Rubin's narrator is earnest and describes his situation with more than a touch of post-adolescent melodrama: the right words "sink into the darkness," in the future he "may discover myself saved," and then he will "tell the tale of the world." Birnbaum's narrator is more self-mocking: in "So it went" there's the echo of Kurt Vonnegut's fatalistic "So it goes" from Slaughterhouse-Five, words "recede into the distance" instead of "sink into the darkness," and "Then lo, at that point," deflates the pomposity of his talk of salvation through a self-ridiculing awareness of how Biblical he's begun to sound.

Rubin's narrator grandiosely says he will "tell the tale of the world"; Birnbaum's will "set forth a vision"—undercutting himself with more of that ironic pseudo-Biblical diction, and making no claims to universality. Finally, Rubin's narrator is "wrestling" with his dilemma, while Birnbaum's is "caught" in his, a word that seems better to capture the narrator's detachment and passivity. Birnbaum's translation is sometimes clunky—"sometime way ahead, years, maybe decades, from now" has a lot of commas over the course of a very few words. And there would seem to be a significant difference (which I can't resolve) between an elephant trainer and an elephant keeper (Ted Goosens' later translation also uses "trainer"). But to my mind's ear Rubin's translation is no less clunky—"discover myself saved" as an example—and his choices makes the narrator sound as though he's lacking the ironic self-awareness of Birnbaum's.

Image source: Raptis Rare Books

As Birnbaum finished his translation of Hear the Wind Sing, Murakami published his fifth novel, Noruwei no mori (Norwegian Wood) in September 1987. [5] It became a massive bestseller, selling millions of copies over the next 15 months. Birnbaum's editor Jules Young requested that he translate it immediately for the English Library.

Birnbaum was unenthusiastic. He found that the novel was "missing the humor and surreal aspects I liked" and was "a bit sentimental," and he had already started translating A Wild Sheep Chase. But he did not have the luxury of turning down a job, and so he agreed to do both. I think Birnbaum's hesitations were justified. If Norwegian Wood had been the first Murakami novel I read, I doubt that I would have been interested in reading any of his other fiction.

This time Murakami's narrator has a name—Tōru Watanabe—and is once again looking back at his college-age self from Murakami's age at the time of writing (38). The novel takes place against the distant background of the Japanese student movement of the late 1960s. In the foreground are the love troubles of the young Tōru, who has come from his home town of Kobe to attend university in Tokyo (again, like Murakami himself).

Tōru is torn between two women. The first is Naoko, the former girlfriend of Tōru's best friend in high school, Kizuki. Death seems to surround her: both Naoko's sister and Kizuki committed suicide, and she herself has dark thoughts that have resulted in her leaving college to go to a sanatorium-like retreat in the mountains. The second woman in Tōru's life is the lively, outgoing, un- (or less-) complicated Midori, who makes overtures to Tōru even though she already has a boyfriend. Yes, it's a woman who represents the death drive versus a woman who represents the life force.

Complicating matters is Naoko's roommate at the sanatorium, a 39-year-old woman named Reiko, who pours out her life story to the sympathetic Tōru. That story involves her experiences as a musician, wife and mother, until her lesbian seduction (recounted at multi-page length and in explicit detail) by a beautiful but malevolent 13-year-old (!) student. Reiko's marriage and career are destroyed, and she has a breakdown that brings her to the sanatorium. [6]

Rubin calls Reiko's tale "a compelling, heartbreaking story" that has the reader "hanging on every word" (p. 4). Another perspective might be that her story indulges in tiresome clichés about predatory lesbians, and provides prurient details for the titillation of both Tōru and the reader.

Reiko's friendship with Tōru ultimately leads her to leave the illusory safety of the sanatorium to go stay with Tōru in Tokyo. The (literal) seductions of lesbianism are, of course, vanquished by a night of passionate (unprotected, intergenerational and semi-incestuous) sex with the straight hero. [7]

It's been a while since I've read Norwegian Wood, but I don't think I'm exaggerating its schematic and stereotypical qualities. But despite (or perhaps because of) those qualities it made Murakami the most successful novelist in Japan. In 2010 it was adapted as a film by writer-director Anh Hung Tran.

Given Murakami's subsequent international fame, it's curious that Hear the Wind Sing, Pinball, 1973, and Norwegian Wood were available in English in Japan a least a decade before they were published in any English-speaking country. (Norwegian Wood was published in the U.S. in a new translation by Rubin in 1999, and the first two novels were published in new translations by Ted Goosens in 2015.) But perhaps this was a wise choice on the part of Kodansha. I bought all three English Library titles as imports at the Kinokuniya Bookstore in San Francisco's Japantown after reading the U.S. edition of A Wild Sheep Chase shortly after it came out. I recall being disappointed in each of them. The two short novels seemed slight, and Norwegian Wood seemed conventional in the worst senses, in comparison to the first Murakami novel published in the U.S.: A Wild Sheep Chase. [8]

Next time: Murakami's first U.S. publications: A Wild Sheep Chase and Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World.

Other posts in this series:

- The transition: The Elephant Vanishes (1980-91/1993) and Dance Dance Dance (1988/1994)

- International breakthrough: The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle (1995/1997)

- Film adaptation: Ryūsuke Hamaguchi's Drive My Car (2021)

- Comics adaptation: Jean-Christophe Deveney and PMGL's Manga Stories (2023)

- More film adaptations: Burning (2018) and Norwegian Wood (2010)

- This is often described as a "jazz bar," but it didn't feature live bands; Murakami played jazz records as background music.

- In A Wild Sheep Chase, the third novel in the so-called "Rat Trilogy" and which takes place half a decade later, Boku will go in search of the Rat.

- In the foreword to the U.S. publication of the first two novellas (in a

new translation by Ted Goosens), Murakami reports that his breakthrough

into writing was to compose the opening passages of Hear the Wind Sing in English after the manner of the American writers he was currently reading, such as Raymond Chandler and Raymond Carver. He then "translated" the passages back into Japanese. In the early 1980s Murakami had begun to translate American fiction into Japanese, and the boku-hero of Pinball, 1973 has set up an English translation agency with the Rat.

- It's interesting that this passage describes the narrator's inability to write about an elephant keeper. The disappearance of an elephant and his keeper will be the central event in Murakami's later short story "The Elephant Vanishes," and elephants will turn up in several of Murakami's other stories and novels. Again, an apparently casual or random reference turns out to be a recurring motif.

- "Noruwei no mori"—literally, "A Forest in Norway"—is, according to Rubin, "the standard Japanese mistranslation of The Beatles' song 'Norwegian Wood'," which features repeatedly in the novel. (p. 149)

- I don't recall the disturbing detail of the student's age in Birnbaum's translation, but it is definitely present in Rubin's later retranslation. Bisexual or lesbian characters also recur in Murakami's fiction.

- The apparently irresistible sexual magnetism of Murakami's protagonists,

who are frequently provided with semi-autobiographical characteristics,

is another frequent feature of his fiction. In 1Q84 (2009/2011), a beautiful bisexual assassin has a deep sexual attraction to middle-aged men with receding hairlines; in 2009 Murakami turned 60.

- I was so disappointed in Norwegian Wood that I sold my two-volume red and green English Library copy to a used bookstore. I probably got $5 for both volumes. These days copies of the two-volume English Library edition, even in later printings, are selling for hundreds of dollars; signed first printings go for thousands.

No comments :

Post a Comment