Favorites of 2022: Recordings

As we approach the end of the year it's time once again for me to choose my favorites, starting with recordings first heard in the past twelve months. The order within each category is roughly chronological by period of composition.

SECULAR AND SACRED MUSIC

Hispania & Japan: Dialogues. Montserrat Figueras (soprano), Prabhu Edouard (tabla), Ken Zuckerman (sarod), Yukio Tanaka (voice, biwa), Masaka Hirao (viola da gamba tenor), Hiroyuki Koinuma (shinobue, nokan), Ichiro Seki (shakuhachi); La Capella Reial de Catalunya, Hesperion XXI, Jordi Savall, direction. Alia Vox AVSA9883 (recorded 2006-2007; released 2011).

Image source: Presto Music

The impetus for this recording is "to create a true dialogue between the spiritual music of Japan and the Hispanic world at the time of St. Francis Xavier's arrival in Japan" in 1549. Some of the tracks are 16th-century liturgical music performed by Hesperion XXI and La Capella Reial de Catalunya, while others are traditional Japanese pieces performed by the Japanese musicians. There are also improvisations on the plainchant "O Gloriosa Domina" by (separately) the Japanese and European musicians. In commemoration of the time St. Francis spent in India before and after his sojourn in Japan, Montserrat Figueras performs the devotional villancico "Senhora del Mundo" (Sovereign Lady of the World) accompanied by sarod and tabla. It is all utterly mesmerizing, and recommended even if you share my general skepticism of fusion projects.

Improvisation on "O Glorioso Domina" by Ichiro Seki (shakuhachi):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oAWFYoQhvws

Salve Regina: Leo, Pergolesi, Porpora. Federica Napoletani (soprano); Ensemble Imaginaire, Cristina Corrieri, conductor. Brilliant Classics 96092 (recorded 2018; released 2020).

Image source: Presto Music

Nicola Porpora (born 1686), Leonardo Leo (born 1694), and Giovanni Pergolesi (born 1710) were all composers who received their early training in Naples. Each composed both operas and sacred music, and operatic style is sometimes apparent in these settings of Salve Regina. This Marian hymn is sung during services in the six months between Pentecost and Advent; because it was so frequently performed, composers (including these three) often produced multiple versions. The settings are stylistically varied, and so there is no flagging of interest despite each version setting the same text. In addition, two of the settings (Porpora's and Pergolesi's) are world premiere recordings. Federica Napoletani has a lovely soprano, and, together with Ensemble Imaginaire, elegantly meets the technical and interpretive challenges of these works.

The first movement of Nicola Porpora's Salve regina in G Major:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TyTCbHyX7f0

Pardessus de Viole: Barrière, Caix D'Hervelois, Boismortier, Dollé. Mélisande Corriveau (pardessus de viole), Eric Milnes (clavecin). ATMA Classique ACD2 2729 (recorded 2015; released 2016).

Image source: Presto Music

The pardessus de viole is the smallest and highest-pitched viola da gamba; its name means "higher than the treble viol." It was developed in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, and was considered more seemly for women to play because it was held upright on the lap rather than gripped between the legs. Its range overlapped with that of the violin, but the playing position of the violin (tucked underneath the chin) was thought to be inelegant for women; in 1748 Michel Corrette wrote that "ladies shall play the pardessus with five strings and never the violin, as the position involved in playing the violin in no way suits them." The pardessus thus became known as "le violon des femmes," or women's violin, although men also played it.

La joyeuse de pardessus de viol by Jean-Baptiste Perronneau, mid-18th century. Image source: Musica Picta on Tumblr

Composers responded to the fashion for the pardessus de viole by writing pieces specifically for the instrument, both for amateurs at varying levels of skill and for professional musicians. On this disc Mélisande Corriveau has selected works by four French composers for performance on a sweet-toned instrument dating from 1710 held in the Hart House Collection of the University of Toronto. Corriveau plays these virtuoso pieces not only with astonishing technical assurance but also with pleasing expressiveness. Eric Milnes provides discreet harpsichord accompaniment, but the focus, as it should be, is firmly on Corriveau. A wonderful way to discover a repertory that was new to us.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ER0CYHTQY7Y

A Night in London. Sandrine Piau (soprano), Lucille Richardot (mezzo-soprano); Pulcinella, Ophélie Gaillard, cello and direction. Aparté AP274 (recorded 2021; released 2022).

Image source: Presto Music

Cellist Ophélie Gaillard's album presents music that might have been encountered over the course of a single adventurous evening in London during the 1700s. As our imaginary listener moves from coffee house to concert hall to opera house to tavern, we hear music ranging from James Oswald's "She's Sweetest When She's Naked" to concert music by Avison, Geminiani, Porpora, Hasse, and Cirri, to an aria from Handel's Alcina, before ending with Oswald's "The Bottom of the Punch Bowl." From the cello, Gaillard directs the period-instrument chamber orchestra Pulcinella in the concerted pieces. While the music probably covers too wide temporal range (1720s to the 1760s) to have been plausibly encountered in a single evening, much of it was new to me and it is all impeccably performed by Gaillard, Pulcinella, and their guest vocalists.

James Oswald's "She's Sweetest When She's Naked" (solo version):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4tyCuT_uJn8

Mr. Abel's Fine Airs. Susanne Heinrich (viola da gamba). Hyperion CDA67628 (recorded 2006; released 2007).

Image source: Presto Music

The music historian Charles Burney (father of Jane Austen's favorite novelist Fanny Burney) attended many of Carl Friedrich Abel's London concerts, and wrote, "His performance on the viol da gamba was in every particular complete and perfect. He had a hand which no difficulties could embarrass; a taste the most refined and delicate; and a judgment so correct and certain, as never to let a single note escape him without meaning." On this recording Heinrich performs Abel's Sonata in G major, together with 20 relatively brief pieces for solo viola da gamba from a manuscript of Abel's works once owned by the painter Thomas Gainsborough, later purchased by the financier Joseph Drexel, and now held by the New York Public Library. Her approach is beautifully measured, reflective, and inward. There is another wonderful recording of 29 of the pieces from the Drexel Manuscript by Paolo Pandolfo in which he plays them in a more extroverted and exuberant style, but Heinrich's is the recording we found ourselves returning to more often. For my full-length post on Carl Abel, please see "Exuberance and profound sweetness."

Listen to extracts from the album (Hyperion Records)

OPERA

Maria Teresa Agnesi: Arias from the opera Sofonisba. Elena De Simone (mezzo-soprano); Ensemble Il Mosaico. Tactus TC 720102 (recorded 2019; released 2021).

Image source: Presto Music

From my full-length post "African Queen: Sofonisba" (slightly edited): Maria Teresa Agnesi was born in 1720 to a wealthy merchant family in Milan, a city which was then a part of the Austrian Habsburg Empire. There were two exceptionally gifted daughters in the family: Maria Teresa in music and her older sister Maria Gaetana in mathematics and philosophy. Their father held regular gatherings in their home during which Maria Gaetana would give talks and debate with learned men, and Maria Teresa would perform. An admiring account from 1739, when Maria Teresa was 18, reports that she played harpsichord pieces by Rameau and accompanied herself as she sang arias of her own composition.

Maria Teresa Agnesi, artist and date unknown. La Scala Museum. Image source: Pinterest

A decade or so later she composed La Sofonisba, an opera seria about the (possibly mythological) African queen. Betrothed to the Eastern Numidian prince Massinissa, Sofonisba is instead forced by her father to marry Siface (Syphax), the Western Numidian king with whom Hasdrubal wishes to make an anti-Roman alliance. Stung by Sofonisba's marriage to his rival, Massinissa revolts against Siface and joins forces with the Roman general Scipio. Together they defeat Hasdrubal and Siface in battle, taking as prisoners both Siface and his wife. Ultimately, rejecting her husband, abandoned by the man she loves, and facing dishonor, Sofonisba consumes poison and dies.

No printed libretto for the opera survives, and so the poet is unknown. The work exists in a single copy: the presentation score that was sent to Vienna for the name-day of the Empress Maria Theresa, 15 October (also the name-day of the composer). The score is not dated, but it is likely to have been completed in the late 1740s; it is dedicated to the Holy Roman Emperor Francis I, Maria Theresa's husband, who was elevated to that office in 1745. There are no performance markings in the presentation score, but it would not have been used in an actual production (copies would have been made). However, the absence of any performance parts, printed libretto, or record of a production makes it seem unlikely that the opera was ever performed.

Title page of La Sofonisba by Maria Teresa Agnesi. Image source: Österreichische Nationalbibliothek

We might speculate that one reason for a lack of performance could be the apparently odd choice of a subject for a celebration of the Empress's name-day. After all, Sofonisba is forced to marry a man she doesn't love, is militarily defeated, held captive, and commits suicide. But Sofonisba's choice of death rather than dishonor places her in the company of other noble women from antiquity who were extolled for their courage, such as Dido and Cleopatra.

Like Dido and Cleopatra, Sofonisba ruled in North Africa. And this, along with the role's low vocal range, suggests that the opera may have been intended as a vehicle for the contralto Vittoria Tesi Tramontini, the first Black prima donna, who by the late 1740s was living in Vienna.

Tesi, the daughter of an African servant at the Medici court in Florence, was known as "La Moretta," the Dark One (she was also known as "La Fiorentina"—The Florentine—and "La Tesi"). Born in 1700, she first appeared onstage in 1716. Over the course of her four-decade career she appeared in theaters throughout Italy, Austria and Germany with colleagues such as mezzo-soprano Margherita Durastanti and the castrati Farinelli, Senesino and Caffarelli.

On the album Arie dall'opera Sofonisba the mezzo-soprano Elena De Simone, accompanied by the ensemble Il Mosaico, performs seven arias from Agnesi's Sofonisba, plus its Licenza, or celebratory epilogue in honor of Maria Theresa; De Simone also edited the performance score. As a listening experience the album is highly recommendable: De Simone has a rich, low voice that easily encompasses the wide vocal and emotional range of Sofonisba's arias, and Il Mosaico offers excellent support (and the natural trumpets used in two of the arias have a nicely pungent tone). The record would be valuable alone for showcasing the under-celebrated work of Agnesi and Tesi, but the high quality of the performances means that it will recommend itself to all lovers of Baroque opera.

Elena De Simone. Image source: MusicVoice.it

Sofonisba's aria "Dubbia ancor" from Act I, Scene 2:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KqP8GFTdumo

Gioachino Rossini: Early Operas: La cambiale di matrimonio (The marriage contract, 1810); La scala di seta (The silk ladder, 1812); L'occasione fa il ladro (Opportunity makes the thief, 1812); Il signor Bruschino (1813); Il barbiere di Siviglia (The barber of Seville, 1816). Monica Bacelli, Cecilia Bartoli, Alessandro Corbelli, Carlos Feller, David Kuebler, and others; Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Gabriele Ferro (Il barbiere di Siviglia) and Gianluigi Gelmetti; staged by Michael Hampe and directed for video by Claus Viller. EuroArts/Schwetzingen SWR Festspiele (recorded 1988-1992; re-released 2022); 5 DVDs.

Image source: Euroarts

A shocking confession: when I went to see the January 2004 San Francisco Opera production of Rossini's Il barbiere di Siviglia (The Barber of Seville) featuring Matthew Polenzani as Count Almaviva/Lindoro, Thomas Hampson as Figaro, and Joyce DiDonato as Rosina, I left at intermission (to the astonishment of my standing-room mates). I wasn't dissatisfied. Quite the opposite: I was thoroughly satisfied, but I had reached my Rossini saturation point.

My tastes definitely skew toward Baroque and Classical opera; for me, Rossini marks the boundary between operas I'm passionate about and those that (with a few exceptions) I can live without. Rossini is not Mozart. [1]

So this collection of Rossini's early comedies (written when he was between the ages of 18 and 24) seems designed to appeal to me. Only Il barbiere has a second act; all the others are one-acts that clock in at around 90 minutes—the perfect amount of Rossini, as far as I'm concerned. The characters are somewhat stock, as are the situations, and Rossini often falls back on patter songs to draw laughs (works on me every time. . .for 90 minutes). But all the operas succeed admirably as breezy entertainments that don't overstay their welcome. And each is staged in a straightforward (but effective) way by Michael Hampe in the Rococo jewel box Schwetzingen Palace Theatre.

Schwetzingen Palace Theatre. Image source: visit-schwetzingen.de

Despite its expansion into a second act, Il barbiere di Siviglia is a key attraction of this set because it features a 21-year-old Cecilia Bartoli in one of her first starring roles as Rosina, a young woman held as a virtual prisoner by her elderly, lecherous guardian. But each opera is cast with exceptional character singers who know how to bring out all the comedy (and even some pathos) without relying too heavily on schtick.

Rosina's Act I aria "Una voce poco fa" ("A voice heard a moment ago." Apologies for the poor video resolution and audio quality; the new DVDs are much better):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cVFtLh08mcM

Honorable mention:

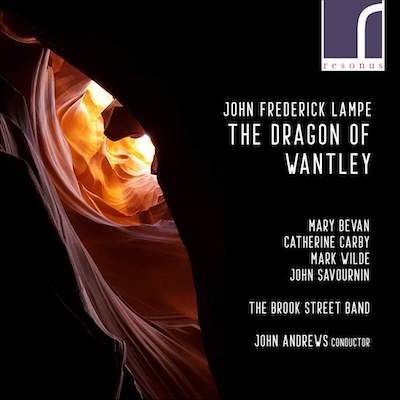

John Frederick Lampe: The Dragon of Wantley (1737). Mary Bevan (soprano, Margery), Catherine Carby (mezzo-soprano, Mauxalinda), Mark Wilde (tenor, Moore of Moore Hall), John Savournin (bass, Gaffer Gubbins/The Dragon); The Brook Street Band, John Andrews, conductor. Resonus RES10304 (recorded 2021; released 2022).

Image source: Presto Music

Some music historians claim that John Gay's The Beggar's Opera (1728) doomed Italian opera in London. However, in the decade after The Beggar's Opera ended its lengthy initial run Handel produced some of his greatest works, including Partenope (1730), Orlando (1733), Ariodante (1735), Alcina (1735), and Serse (1738).

A more plausible culprit is John Frederick Lampe's The Dragon of Wantley (1737). Lampe was a bassoonist in Handel's orchestra and had thoroughly absorbed Handel's style. From its martial overture to its sung recitative, da capo arias and fugal choruses, The Dragon of Wantley parodied the conventions of opera seria with music that was "as grand and pompous as possible" (according to librettist Henry Carey's preface).

Carey's libretto was based on an old comic ballad published by Thomas D’Urfey in Pills to Purge Melancholy (1699). The ballad tells the story of a dragon that terrorizes South Yorkshire until a knight (Moore of Moore Hall), clad in spiked armour, kills it by kicking its behind (literally), its only vulnerable spot.

"Moore fighting with ye Dragon." From Bickham's Musical Entertainer, Vol. II, C. Corbett, London, 1740, p. 32. Digitized by University of Western Ontario - University of Toronto Libraries. Image source: Internet Archive

Carey added the characters of Gaffer Gubbin (a gaffer is a rustic old man), his daughter Margery, and Margery's rival for Moore's affections, Mauxalinda (a maux is a slattern).

The dragon satirizes the corpulent Sir Robert Walpole, whose Whig government had proposed increasing taxes on wine and tobacco and recently succeeded in raising the tax on gin (riots resulted). Gubbin sings, "What wretched havoc does this Dragon make! / He sticks at nothing for his Belly's sake / Feeding but makes his Appetite the stronger / He'll eat us all if he bides here much longer!"

Margery leads the townspeople to Moore Hall to demand that Moore vanquish the dragon. He agrees if she'll give him a kiss, exciting the jealousy of his mistress Mauxalinda; the two women trade insults in a duet that pokes fun at Handel's Rival Queens Faustina Bordoni and Francesca Cuzzoni.

"Moore Coaxing Mauxalinda." From Bickham's Musical Entertainer, Vol. II, C. Corbett, London, 1740, p. 12. Digitized by University of Western Ontario - University of Toronto Libraries. Image source: Internet Archive

Finally, after donning his armour Moore is ready to sally forth and battle the beast. "But first I'll drink, to make me strong and mighty / Six Quarts of Ale, and one of Aqua Vitae." Thus fortified, he delivers his fatal kick, wins the love of Margery, and becomes the subject of a "Roratorio" (anticipating John Cage's Roaratorio by 240 years).

"Moores Engagement to Margery." From Bickham's Musical Entertainer, Vol. II, C. Corbett, London, 1740, p. 8. Digitized by University of Western Ontario - University of Toronto Libraries. Image source: Internet Archive

The Dragon of Wantley was a huge hit, running for 69 performances after its move in the fall of 1737 from the Little Theatre in the Haymarket to Covent Garden. This spelled disaster for Handel's opera season. Despite the presence of Caffarelli and La Francesina in the casts, both of his new operas for the 1737-1738 season failed: Faramondo ran for eight performances, and Serse only five. Over the next three seasons Handel would write only two more Italian operas (which together would only muster as many performances as Serse) before ceasing opera composition entirely.

Despite being the principal target of The Dragon of Wantley's parody, however, Handel praised Lampe's music. Lord Wentworth recorded, "I like it vastly & the music is excessive pretty, & tho' tis a burlesque on the opera's, yet Mr Handel owns he thinks the tunes very well compos'd."

The comedy is generated not only by the farcical action but by the contrast between the text and the elevated music. The excellent ensemble cast on this first professional recording deliver their lines with perfectly straight faces, and The Brook Band under conductor John Andrews gives a spirited performance. This just misses being a favorite in part because it has a tenor hero and in part because I'm not sure how often I'll need to hear it: farce works best with a laughing audience surrounding you. But applause to all concerned for helping to resurrect a significant work in English operatic history. If you're a fan of Handel's operas you'll want to give The Dragon of Wantley a listen.

The conclusion of Act II: "Fill the mighty Flagon / Then I'll kill this monstrous Dragon":

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8c0C9132WPA

SEA SHANTIES (AND OTHER WORK SONGS)

Smoke & Oakum. The Longest Johns: Jonathan "JD" Darley (vocals, guitar), Dave Robinson (vocals, tin whistle), Robbie Sattin (vocals, harmonium, organ, harmonica) and Andy Yates (vocals, banjo). Decca 3876697 (released 2021).

Image source: Discogs.com

After singing sea shanties in close harmony for a decade in their home port of Bristol and around the UK, The Longest Johns had a fluke internet hit with "The Wellerman." That brought them a deal with Decca and (I'm guessing) some support for a North American tour, which gave us a chance to see them earlier this month half a world away from Bristol at the Great American Music Hall in San Francisco. It was a great show, even though for most of the set the band was down a man: Robbie Sattin couldn't get a visa in time. (He participated virtually in several of the songs and some of the between-numbers patter.) The band's mixture of traditional and original work songs invites singing along, and the enthusiastic audience did so with every tune.

From Smoke & Oakum, the Longest Johns' a capella arrangement of Ed Pickford's "The Workers Song":

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qDqzxHFNmq8

Other Favorites of 2022:

- On Exotic & Irrational Entertainment I have written posts on more than 60 operas. More than 40 of them were composed in the two centuries between 1600 and 1799, while only 10 were composed in the 1800s.

For the record, the operas I've written about that premiered in the 1800s are:- Hector Berlioz, Les Troyens (The Trojans, 1858)

- Félicien David, Lalla-Roukh (1862)

- Gaetano Donizetti, Lucia di Lammermoor (1835)

- Gaetano Donizetti, Maria Stuarda (1834)

- Ruggero Leoncavallo, La Boheme (The Bohemians, 1897)

- Jacques Offenbach, Les Contes d'Hoffmann (The Tales of Hoffmann, 1881)

- Giacomo Puccini, La Bohème (The Bohemians, 1896; also discussed in The other Boheme)

- Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Eugene Onegin (1879)

- Giuseppe Verdi, Aida (1861)

- Giuseppe Verdi, La Traviata (The Lost One, 1853).

No comments :

Post a Comment