Your head may go reeling: Pre-code musical Murder at the Vanities

Murder at the Vanities (1934). Screenplay by Carey Wilson and Joseph Gollomb, dialogue by Sam Hellman, based on the play by Earl Carroll and Rufus King; directed by Mitchell Leisen.

Murder at the Vanities was released on May 18, 1934. It was barely in time. Just six weeks later, on July 1, the major Hollywood producers placed censorship of their movies in the hands Joseph Breen's Production Code Administration. Both scripts and final cuts had to receive Breen's stamp of approval. Under Breen there would be far less sexual suggestiveness, fewer scantily-clad chorus girls, fewer changing-room scenes, fewer suggestions of police incompetence and corruption, and fewer murders going unpunished.

Fortunately Murder at the Vanities got in under the wire, and so we can enjoy (and/or be appalled by) the elements that make Pre-Code Hollywood movies so engaging, including:

- Bit players unaware that they will soon become stars:

Could that redheaded chorine among the blondes be Lucille Ball? Also appearing as an uncredited Vanities chorus girl, according to IMDB: Ann Sheridan.

- Stars unaware that their Hollywood careers will soon end:

Handsome former Danish prizefighter and Hitchcock actor Carl Brisson, whose Hollywood career would continue for only two more movies after he appeared as crooner Eric Lander in Murder at the Vanities.

- Julliard- and Royal Academy of Dramatic Art-trained performers slumming it in Hollywood:

Vanities headliner Ann Ware was 23-year-old Kitty Carlisle's first film role. The following year she would star in the Marx Brothers' A Night at the Opera before returning to New York and the Broadway stage.

- Song lyrics extolling consciousness-altering substances:

Gertrude Michael as Rita Ross performing Arthur Johnston and Sam Coslow's "Sweet Marijuana." Yes, that is a chorus line of guitarists in sombreros behind her. (And could the guitarist over her right shoulder be a young Alan Ladd?)

- More song lyrics extolling consciousness-altering substances:

- Yet more song lyrics extolling consciousness-altering substances:

Before vanishing into undeserved obscurity Carl Brisson introduced Johnston and Coslow's "Cocktails for Two," which begins, "Oh what delight to/be given the right to/be carefree and gay once again./No longer slinking,/respectably drinking,/like civilized ladies and men." Prohibition had been repealed just five months before Murder at the Vanities was released. [1]

- Chorus girls with strategically placed seashells:

- Chorus girls with strategically placed seaweed:

- Chorus girls with strategically placed upper limbs:

- Black and white dancers and musicians performing together:

Gertrude Michael as Rita Ross singing "Ebony Rhapsody" with dancers and Duke Ellington and His Orchestra.

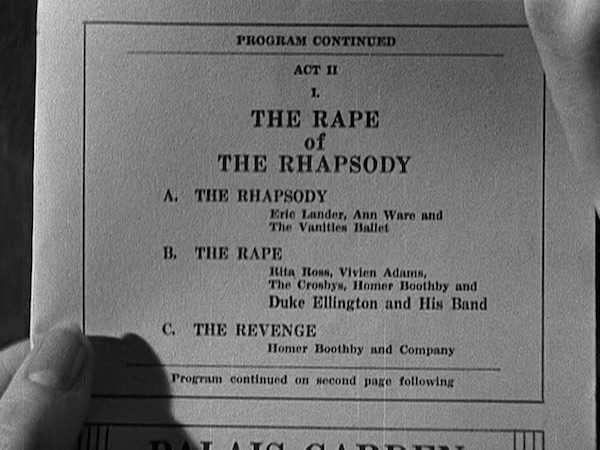

The deliriously incorrect number from which the above still is taken is worth taking a look at in a little more detail. The production number takes up a full eight and a half minutes of the movie's 89-minute running time and is called "The Rape of the Rhapsody":

The number opens with Eric Lander portraying Franz Liszt as he composes the Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2:

He is visited by Ann Ware's Muse and an inspiring vision of a stately dance by couples wearing Hollywood's idea of Broadway's idea of 19th-century dress (lots of flounces and feathers):

The scene dissolves into an orchestra playing a syrupy version of the Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2, surrounding by an admiring audience of those couples:

But then jazz musicians emerge from behind the orchestra players and a brassy flourish disrupts the music's measured pace:

The jazz musicians quickly duck back down, and the puzzled conductor thinks his own musicians are deviating from the score. He tries to continue, but it happens again, and again. The orchestra gives up and the jazz musicians take their places. Curtains at the back of the stage part to reveal an elegant man in a tuxedo: Duke Ellington.

As the band swings into a jazzy version of Liszt's melody, the conductor rages: he tears at his hair, shakes his fist at Ellington and finally stomps off.

Now a chorus line of black women dressed as maids comes forward, and Rita Ross begins singing "Ebony Rhapsody":

There's rhythm down in Martinique isle

That has any minuet beat a mile

For low-down quality

And they call it the Ebony Rhapsody

Instead of playing music like you do

They supply a little classical voodoo

They keep swingin' that thing

And singin' that Ebony Rhapsody

It's got those licks, it's got those tricks

That Mr Liszt would never recognize

It's got that beat, that tropic heat

They shake until they make the old thermometer rise.

Soon the white couples in 19th-cenury attire are dancing along, with the women lifting their petticoats and kicking in unison. This is evidently "The Rape."

Then, "The Revenge": the orchestra conductor bursts back onstage—carrying a submachine gun:

Everyone is "massacred": Rita Ross, a trio of white tap dancers, the black chorus line (though not the white dancers behind them on the stairs), and Ellington's musicians. By the way, the killer conductor Homer Boothby is played by Charles Middleton, later Emperor Ming the Merciless in the Flash Gordon serials.

This number, filled with flagrant cultural appropriation and dubious associations (jazz = Africa + Latin America = the Caribbean = Martinique = voodoo, black women = maids, etc.), not to mention ethnic caricatures, salacious lyrics, suggestive movements and murderous violence, is remarkable even for Pre-Code Hollywood. And the notion that a jazz performance of the Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2 constitutes the defilement of pure European high culture is jaw-droppingly racist, even for the time. At least the conductor is clearly meant to be a villain, not a hero.

Murder at the Vanities may have raised (or lowered) the bar for outrageousness, but the plot is as thin as a chorus girl's body stocking. Backstage at the Earl Carroll Vanities (an actual Broadway revue) someone on the catwalks high above the stage is dropping lighting instruments and sandbags onto the performers below in an attempt to kill Ann Ware. The chief suspect is second-billed singer Rita Ross, who is jealous of Ware's imminent wedding to Eric Lander.

Gertrude Michael as Rita Ross.

Ross also plans to blackmail Lander; she has discovered the secret past of Lander's mother (Jessie Ralph), a former opera star who fled her native Vienna decades ago and has been acting as the head seamstress for the show under an assumed name. But then a detective hired by Lander is found dead, and an attempt is made on Ross's life with a pair of sewing scissors. Meanwhile, police sergeant Bill Murdock (Victor McLaglen) is bumbling around backstage, barging into dressing rooms and leering at the barely-dressed chorus girls while arriving late to the scene of every crime.

The movie originated as a play written by Earl Carroll and Rufus King, which grafted a narrative through-line onto the typical Vanities revue structure. Although the play was a success, it could not rescue the revue format on Broadway. With the development of the sound film, the coming of the Depression, and rise of the integrated musical (in which the songs arose out of the story rather than standing as independent production numbers), high-budget Broadway revues such as the Vanities, Ziegfeld Follies, and George White's Scandals were less and less viable. The final Follies was produced in 1936 and the final Scandals in 1939, while the final edition of the Vanities in 1940 closed after just 25 performances (the 1926-27 edition had run for 303).

Ironically, Hollywood—one of the causes of the decline of stage revues—kept the revue genre going by producing "let's put on a show" musicals. These movies were essentially integrated musicals about the creation of number musicals; examples include Gold Diggers of 1933, The Great Ziegfeld (Best Picture of 1936), Babes in Arms (1939), and The Band Wagon (1953). (Two more movies based on the Vanities, Earl Carroll Vanities (1945) and Earl Carroll Sketchbook (1946), were among them.) Also ironically, the compilations That's Entertainment (1974) and That's Entertainment II (1976), which presented numbers from integrated musicals detached from their narrative context and presented as pure spectacle, were essentially revivals of the revue format.

So Murder at the Vanities represents both the last gasp of the Broadway revue and its rebirth in the backstage musical. And as with many Pre-Code movies, narrative coherence takes a back seat to sensationalism and suggestiveness. Don't say you weren't warned.

Indeed.

Murder at the Vanities is available on DVD in Universal's Pre-Code Hollywood Collection, which also includes Tallulah Bankhead in The Cheat (1931), the early Cary Grant movies Merrily We Go To Hell and Hot Saturday (1932), Claudette Colbert in Torch Singer (1933), and the young Ida Lupino in Search for Beauty (1934).

- A further note on "Cocktails for Two": the song has been recorded by Duke Ellington, Tommy Dorsey, Coleman Hawkins, Bing Crosby, Keely Smith, Ray Charles & Betty Carter, and Charles Mingus, but its most famous recording is the parody version with raucous sound effects by Spike Jones and His City Slickers. Lyricist Sam Coslow wrote of Jones' parody, "I hated it, and thought it was in the worst possible taste, desecrating what I felt was one of my most beautiful songs" (Cocktails for Two: The Many Lives of Giant Songwriter Sam Coslow, Arlington House, 1977, p. 145).

so glad you included that footnote, as i happen to adore that version of the song. Spike Jones is also responsible for this: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6mfs9-ZBM-I

ReplyDelete