Suggested reading: Hidden costs

This edition of Suggested Reading is about the hidden (and not-so-hidden) costs of actions we take and choices we make, often unthinkingly.

Container ships waiting to be unloaded at the ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles last week.

Image source: New York Times.

1. Shipping

In one sense, the cost of shipping is essentially zero. As John Lanchester explains in the London Review of Books, thanks to the innovation of the shipping container in the 1950s loading and unloading a ship more than 1000 feet long now requires a matter of hours and a few crane operators, not days or weeks and dozens of men. Sailing huge vessels holding perhaps 20,000 twenty-foot equivalent units (i.e., 20-foot-long containers) across thousands of miles of ocean involves crews of only 20 or 25.

But the negligible direct costs of shipping means that "90 Per Cent of Everything" (in the words of Rose George) is grown, extracted or made across the globe from where it is consumed. I live in one of the most productive farming regions of the planet, and yet find agricultural products from Mexico, Chile, South Africa and Australia on display in my corner grocery. The huge towers for the wind turbines currently being installed in the North Sea are made in Vietnam, one of the low-wage, low-regulation countries to which manufacturing in many sectors has shifted. The first five shirts in my closet were sewn in Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, India, and Sri Lanka, respectively, but the constituent materials (raw cotton, cloth, thread and buttons) may have been sourced from three or four other countries. In 2013 Planet Money traced the supply chain for the show's T-shirts and found that it involved multiple countries and 20,000 miles of travel (if interested in more detail you can view the 15-minute video series or listen to the full 120-minute, 6-episode podcast).

Such lengthy and complex supply chains are marvels of logistics—until they break down. And that breakdown can be due to many disrupting factors, a situation recently brought home, as it were, by the Ever Given (the ship that in March got stuck sideways in the Suez Canal, blocking all traffic for six days) and by the recent and continuing shortages of gas, lumber, food, PPE, computer chips, and batteries. In some cases low supply and spiking prices are due to a shortage of raw materials; in some cases, a shortage of workers; in some cases, a shortage of transport; and in some cases, political hostility.

And although shipping is energy-efficient, because of its immense and increasing volume it has significant environmental effects:

. . .marine transportation still generates negative impacts on the marine environment, including air pollution, greenhouse gas emissions, releases of ballast water containing aquatic invasive species, historical use of antifoulants, oil and chemical spills, dry bulk cargo releases, garbage, underwater noise pollution, ship-strikes on marine megafauna, risk of ship grounding or sinkings, and widespread sediment contamination of ports during transshipment or ship breaking activities.

In addition, Lanchester reports that the International Transport Workers Federation estimates that 2,000 crewmen lose their lives at sea every year. Some things to think about the next time you reach for that out-of-season tomato grown in a different hemisphere.

Image source: Kew.org

2. Cotton tote bags

Although consumerism causes environmental damage, we are often told that the solution lies in being better consumers. Plastic bags, for example, ultimately wind up in landfill or the oceans, where they can persist for centuries. So clearly when we go shopping we should be using one of those ubiquitous cotton tote bags rather than plastic. And an organic cotton tote would be the greenest choice of all, no?

Not necessarily. Cotton is a highly water-intensive crop grown in increasingly drought-prone areas. And although cotton grown with organic methods has a significantly better environmental profile than cotton grown using conventional (i.e., polluting and worker-exposing pesticide- and herbicide-dependent) methods, it has a significantly lower yield per acre. Also, the vast majority of the world's cotton is grown and harvested in countries where forced labor or child labor has been documented in its production, such as India, China, Brazil, Pakistan, Uzbekistan, Turkey, Mali, and Benin (eight of the top ten cotton producers in 2021/22, according to the ICAC; the other two are the US (#3) and Australia (#8)).

As Grace Cook reported recently in the New York Times, the Ministry of Environment and Food of Denmark recently estimated that a single organic cotton tote bag needs to be used daily for 54 years (that is, 20,000 times) to match the human and environmental costs of a low-density polyethylene (LDPE) shopping bag that is reused once as a garbage bag and then incinerated. By their estimate a conventionally-grown cotton tote "only" requires 7100 uses, or a mere 20 years of daily use, to offset its excess costs over LDPE, while a brown paper bag requires 43 uses. We can be skeptical of these figures while at the same time recognizing that choices of plant fibers and even organic agricultural methods can have costs that we have not taken into account. (For the record: I'm in favor of both.) Take note if you (like me) have a pile of cotton totes at home: maybe the next time you are offered a "free" new tote bag, you should turn it down.

Image source: Sulamith Sallmann, CC BY-SA 4.0

3. The vinyl revival

In 2019 I predicted we'd reached peak vinyl. As with my prescient previous predictions about the quick demise of desktop computers, tablets, and smart phones, I couldn't have been more wrong (hey, at least my record of bad market predictions remains unbroken!). In 2020 sales of vinyl records surpassed those of CDs for the first time since 1986, according to the RIAA. And it wasn't even close: vinyl sales totaled $626 million, while CD sales totaled $483 million.

But the toxic impact of the production of vinyl records has been well documented for decades. Vinyl records are made of petroleum-derived polyvinyl chloride (PVC), which is condensed from vinyl chloride gas, a known carcinogen. Most of the PVC pellets used in the production of records come from Thailand, where environmental regulations and worker protections are lax. US producers of PVC pellets also have poor records: in 2004, executives of Keysor Century Corporation pleaded guilty to felony charges for "exposing workers to toxic fumes, releasing toxic chemicals into the air and dumping toxic wastewater" into the Santa Clara River, as Kyle Devine writes in The Guardian. The company agreed to pay a $4.3 million fine and was ordered to stop production. It declared bankruptcy, leaving behind contaminated soil and groundwater at its industrial plant, which in June 2005 was designated a Superfund site.

So clearly the green solution is to stream music rather than purchasing physical media, no? Not necessarily. As Devine writes,

. . .digital media [are] physical media, too. Although digital audio files seem virtual, they rely on infrastructures of data storage, processing and transmission that have potentially higher greenhouse gas emissions than the petrochemical plastics used in the production of more obviously physical formats such as LPs—to stream music is to burn coal, uranium and gas [uranium isn't burned, but never mind]. . .The devices required to access those infrastructures—smartphones, tablets, laptops—rely on the exploitation of natural and human resources around the world. These products then quickly succumb to fashion and obsolescence, ending up at dump sites, making further claims on other people and places.

Although streaming is more energy-efficient per track than vinyl, that efficiency is offset by increased use. According to MRC/Billboard, in 2020 in the US there were 873 billion song streams. At the official equivalency rate of 10 tracks per album, this represents 87.3 billion albums, as compared to 27.5 million vinyl albums shipped. This means that for every album purchased on vinyl more than 3000 album equivalents were streamed. And while Spotify has released data suggesting that the carbon footprint of their server farms is decreasing, this relies on an accounting trick: Spotify is outsourcing its streaming infrastructure to Google Cloud. Devine points out that "as more and more streaming services subcontract their data storage and processing needs to cloud corporations, they also subcontract responsibility for the energy requirements and carbon emissions of digital music." Devine concludes, "Music, like pretty much everything else, is caught up in petro-capitalism."

Amazon Ring. Image source: Wikimedia

4. Amazon Ring and Apple AirTag

In 2018 Amazon bought the video doorbell company Ring for around $1.5 billion, and immediately did two things: it created the Neighbors app, which allows users to upload video and photos from their Ring cameras as they post about anyone seen in their neighborhood that they consider suspicious. And Amazon partnered with more than 1800 police departments, enabling them to request recorded images directly from Ring users without a warrant. In the year ending last April, more than 22,000 separate requests were made.

As Lauren Bridges writes in The Guardian, "once Ring users agree to release video content to law enforcement, there is no way to revoke access and few limitations on how that content can be used, stored, and with whom it can be shared"; this includes the application of biased facial recognition technology. In the month of December 2019 alone it's estimated that nearly half a million Ring cameras were sold. Bridges concludes that Ring

is extending the reach of law enforcement into private property [ordinarily protected by Fourth Amendment prohibitions against unreasonable search and seizure] and expanding the surveillance of everyday life. . .Ring is effectively building the largest corporate-owned, civilian-installed surveillance network that the US has ever seen.

Ring doorbells and cameras (along with Echo speakers) are also by default incorporated into Amazon Sidewalk, a shared wireless network intended to help solve connection problems for its "smart" home technologies. Users of Ring and Echo are given a very limited time to opt out of Sidewalk, after which their bandwidth becomes generally available to neighbors and passers-by to enable their devices to stay connected (and monitored) and to extend the range of tracking devices such as Tile.

Image source: The Conversation

Not to be left out of the surreptitious surveillance market, Apple has developed AirTag, a small tracking device that can be attached to personal items such as luggage, purses, or keys. AirTags themselves do not broadcast GPS location data—instead they ping any AirTag-compatible Apple device within 300 feet (if you have an iPhone 11 or later or are running iOS 14.5 or later, AirTag is enabled by default). The device uploads its location and the AirTag ID to Apple's servers, from which they are transmitted to the AirTag's owner.

To prevent your phone from being used in this way you must turn off both Bluetooth connectivity and location tracking. But then, of course, you can't operate your phone hands-free, use Bluetooth-connected speakers, earbuds or hearing aids, navigate using GPS, or even locate your phone itself if you misplace it.

The potential for AirTags to be used for tracking someone's movements without their knowledge is immediately apparent. Apple claims to have incorporated safeguards to alert potential stalking victims that they are being tracked in this way, including beeps from the AirTag itself. However, as Paul Haskell-Dowland writes on The Conversation blog,

One experiment showed a tag can be placed on a person and would not trigger any of the safeguards if reconnected to the stalker’s device regularly enough. This could be done by the victim returning home or within range of their stalker within a three-day window.

In essence, Haskell-Dowland writes, if you own an iPhone you are part of "an Apple-operated surveillance network in which millions of us are unwitting participants."

Image source: The Conversation

5. Microsoft Excel

How not to Excel at economics: In 2010 the world was struggling to emerge from the Great Recession. The global financial system had teetered on the brink of collapse, and unemployment, foreclosure and eviction were widespread in wealthy industrialized countries such as the US and the UK. Governments were scrambling to find ways to encourage economic growth. At that moment two prominent Harvard economists, Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff, published a paper that purported to show that in countries in which government debt exceeded 90% of GDP, the economy shrank.

Obviously, you don't want to address an economy in recession by implementing policies that will make it shrink further. Britain's then-Chancellor of the Exchequer, George Osborne, cited the work of Reinhart and Rogoff as his justification when later in 2010 he imposed a decade-long policy of austerity. Additional government support for those who had lost their jobs and homes would not be forthcoming.

There was only one problem: in 2013 it became apparent that Reinhart and Rogoff's data actually showed that in countries where government debt exceeded 90% of GDP, the economy, instead of shrinking, grew by an annual average of 2.2%. In other words there was no basis for austerity measures, which could actually be counterproductive.

How could two economists at the peak of their profession get it wrong so spectacularly and so publicly? Leaving aside the question of political prejudice, the answer is that they did their calculations in Microsoft Excel.

Excel is a very widely used tool, but it has some highly problematic features. One is that formulas are hidden: when you apply an Excel formula to derive a value it is not apparent just by looking at the results which data cells have been used in the calculation. You have to be able to click into the spreadsheet itself to see how the formulas have been defined.

In 2013 a graduate student at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, Thomas Herndon, and two faculty members, Michael Ash and Robert Pollin, were attempting to replicate Reinhart and Rogoff's findings from the data published in their influential paper, and discovered that they were unable to do so. They requested a copy of the original spreadsheet used to make the calculations, and amazingly Reinhart and Rogoff still had it and were willing to share it. Once Herndon was able to examine the spreadsheet he discovered that Reinhart and Rogoff had made a basic error. In calculating the change in GDP they had inadvertently omitted from their averaging formula the data for five countries out of their 20-country sample: minor economies such as Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, and Denmark. (They all rank in the top 25 countries in the world in GDP per capita, ahead of the U.K., France, Japan, and Italy.)

In other words, as Jonathan Borwein and David H. Bailey write in The Conversation, "the key conclusion of a seminal paper, which has been widely quoted in political debates in North America, Europe, Australia and elsewhere, was invalid." And the austerity policies it was used to justify may have set back economic recovery for years, causing untold damage to ordinary people's lives.

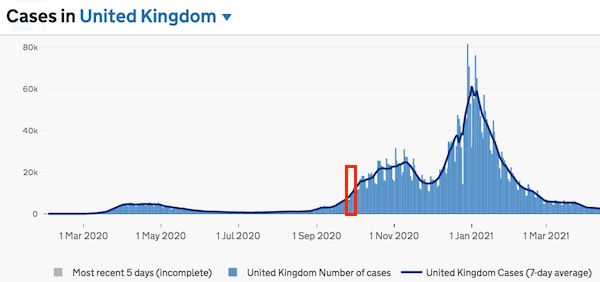

Image source: Gov.uk

Viral errors: In October 2020 Public Health England (PHE) announced that 16,000 confirmed COVID-19 cases were missing from their data for the previous eight days. Although before the data were sent to PHE most people who tested positive had been notified by the places they'd gotten tested, the cases were not entered into PHE's records or into the Test and Trace system of the National Health Service (NHS) until after the error was discovered. How could 16,000 COVID-19 cases simply disappear from the public health system as the virus was starting to surge once more?

As Paul Clough writes in The Conversation, the culprit was once again Excel. PHE was loading the data it received from testing companies and hospitals as comma-separated values (a format widely used to prevent the inadvertent introduction of error) into Excel templates for forwarding to the NHS and other agencies. But in the older version of Excel they were using templates can store only limited amounts of data (sufficient for about 1,400 cases). The rest of the data exceeded the storage limits and simply wasn't saved or forwarded, and for more than a week no one noticed. Newer versions of Excel can store more data, but there are far more robust and checkable data storage and transfer systems that could and should have been used.

As a result of this error, many of those who came into contact with those 16,000 infected and infectious people were not notified that they'd been exposed until enough time had gone by for them to have passed on the virus to others. That due to their poor data practices, the agency tasked with monitoring public health enabled more than a week's worth of untraced transmission involving these cases just at the moment that a new wave of infections was building (and before any vaccine was available) may have had devastating impacts.

Image source: The Conversation

Garbled genes: Another problematic feature of Excel is autoformatting. The spreadsheet has been programmed to recognize certain types of data, and automatically reformats them.

As is well known by anyone who has ever had a text or email message autocorrected into gibberish, these "helpful" features can be highly annoying. But when Excel has been used to store scientific information, any such changes are more than an irritation—they corrupt the data. And as researchers from the US National Institutes of Health discovered in 2004, there are at least 30 gene names, including medically important ones, that Excel interprets as dates. For example, the tumor suppressor gene DEC1 (Deleted in Esophagal Cancer 1) is automatically converted by Excel into the date 1-Dec. And, of course, "1-Dec" is just what Excel displays; the internal code assigned to this date is 36129. In other words, everywhere DEC1 appears in a list of gene names in Excel, it is automatically replaced by the date code 36129. As the NIH researchers wrote, "These conversions are irreversible; the original gene names cannot be recovered."

But this problem has been known since 2004, and so surely researchers stopped using Excel to store genetic data long ago, right?

Wrong. In 2016 Mark Ziemann and his colleagues were digging into the supplementary data files of a highly cited journal article and discovered Excel autoformat gene name substitutions. They decided to investigate how widespread the problem still was by downloading the supplementary Excel files from 3600 articles published in 18 different journals over the previous decade (that is, since the publication of the NIH report warning about the autoformat problem). They found that 20% of articles with supplementary Excel gene lists contained the errors. They published an open access article detailing their findings with the alarming but accurate title "Gene name errors are widespread in the scientific literature."

As a result of this article the Human Genome Organisation's Gene Nomenclature Committee, the international body responsible for official gene names, took the extraordinary step of renaming the most problematic genes. For example, SEPT1 (Septin 1) was renamed SEPTIN1 so that Excel wouldn't misinterpret it. This makes research involving problematic gene names more difficult to search—both new and old gene names now need to be looked for—but given the extent of the problem such a step seemed warranted. And surely now that the problem had been highlighted again and the gene names had been changed, the problem was solved. Right?

Wrong again. This year Ziemann and Mandhri Abeysooriya repeated the analysis on a broader sample of articles published since 2014, and discovered that the problem is even worse. Nearly 30% of their sample of more than 11,000 articles with supplementary Excel gene lists contained autoformat errors (up from 20% in 2016). As they write,

Although changes to gene names and software will help, they won’t solve the overarching problem with spreadsheets: that (i) errors occur silently, (ii) errors can be hidden amongst thousands of rows of data, and (iii) they are difficult to audit. . .The difficulty in auditing spreadsheets makes them generally incompatible with the principles of computational reproducibility.