The madness of love: Layla and Majnun, The Winter's Tale, and Kindra Scharich

As he was walking in the shaft of light from the setting sun, he thought to himself that love is an infected root that seeks out the best way to survive: a fatal illness with an incredibly long course that causes addiction, making the victim prefer suffering to well-being, grief to tranquility, uncertainty to stability.Thanks to a gift from a dear friend I'm currently reading the Commissario Ricciardi novels of Maurizio de Giovanni (the subject of a future post). In the third novel in the series, Everyone in Their Place, love causes ordinary people to feel the unfamiliar, stabbing emotions of anguish, jealousy and hatred, and to contemplate (and sometimes commit) extraordinary acts of violence towards others and themselves. Love, Commissario Ricciardi begins to feel, is a form of madness.

—Maurizio de Giovanni, Everyone in Their Place: The Summer of Commissario Ricciardi (translated by Antony Shugaar)

It's a time-honored theme: a week ago I had the opportunity to witness three performances featuring works spanning half a millennium, all on the madness that love inspires.

Layla and Majnun, Mark Morris Dance Company, with Alim Qasimov (Majnun), Fargana Qasimova (Layla), and the Silk Road Ensemble. Seen in its world premiere performance Friday, September 30 at Zellerbach Hall, Berkeley; commissioned and produced by Cal Performances.

Alim Qasimov and Fargana Qasimova

Layla and Majnun, like Juliet and Romeo, are lovers tragically separated by their families. Layla is forced into an arranged marriage by her parents; Majnun ("madman") then wanders the desert declaiming poems in which his pure love for Layla becomes an aspect of his love for the Divine. When Layla dies Majnun makes a pilgrimage to her grave, where he perishes of grief, uniting with his beloved in death.

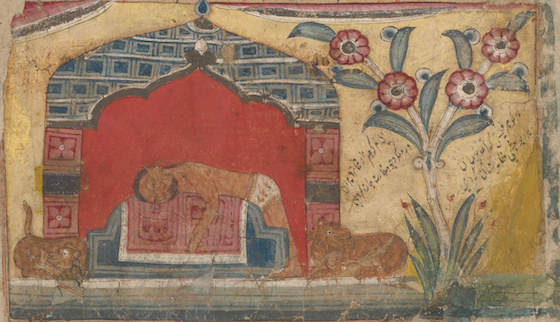

Majnun's death on Layla's grave, ca. 1450

It is a tale with ancient roots and it has been reimagined many times, in many cultures, and in many forms, including plays, novels and films. Perhaps the most renowned version is that by 12th-century poet Nezami Ganjawi, born in Azerbaijan when it was part of the Persian Seljuk Empire. Nezami's epic inspired the 16th-century Azerbaijani poet Füzuli to create his own version. And nearly four hundred years later, Füzuli's version was used by Azerbaijani composer Uzeyir Hajibeyli as the basis of an opera combining Western and Azerbaijani musical forms; the opera is still frequently performed in its country of origin.

A century after the opera's premiere in 1908, it was adapted and condensed by Azerbaijani mugham vocalist Alim Qasimov and musicians of Yo-Yo Ma's Silk Road Ensemble into an hour-long work for two singers accompanied by a chamber orchestra mixing Western, Azerbaijani and Asian instruments. Mark Morris was then invited to choreograph a danced version, and eventually agreed; once again, the story has crossed boundaries of culture and artistic form.

Mark Morris Dance Group and the Silk Road Ensemble in Layla and Majnun

The first thing to say about Morris's Layla and Majnun is that it is less a dance piece accompanied by music than a musical work accompanied by dance. The centrality of the music to the experience of the work was made clear by the staging, which placed the musicians center stage surrounded by a stepped platform; the dancers performed on the platform, at the front of the stage, and occasionally among the musicians.

And the music—particularly the melismatic microtonal mugham singing—is stunning. Here's an example: Alim Qasimov and Faragana Qasimova performing part of the second section of the music of Layla and Majnun with the Silk Road Ensemble:

Rather than designating two soloists as Layla and Majnun, Morris had a different pair of dancers take on the roles in each of the five parts; he seemed to be saying that we are all potential Laylas and Majnuns. The movement vocabulary drew extensively on spinning reminiscent of ecstatic Sufi dancing. I was also reminded by a friend that Morris was once a member of the company of the choreographer Laura Dean, for whom whirling dancers became a signature. That friend also reported that on the second night some of the movement and interactions among the dancers had changed. Morris had clearly given his company the freedom to improvise in response to the vocalists' inspirations.

In the end, the music, the movement, and the striking backdrop by gestural painter Howard Hodgkin (which seemed to shift and change under James Ingalls' atmospheric lighting), combined into a stunning totality in which every element enhanced and enriched the meanings of the others. Another masterpiece from Mark Morris and his collaborators.

The Winter's Tale. Free Shakespeare in the Park. Seen Saturday, October 1 in McLaren Park, San Francisco; produced by the San Francisco Shakespeare Festival.

Happy Bohemians in SF Shakespeare Festival's "The Winter's Tale"

"The Winter's Tale" is one of Shakespeare's "problem plays," dramas in which elements of both tragedy and comedy uneasily coexist. It was a bold choice for Free Shakespeare in the Park, because it's not an obvious crowd-pleaser: the mixed character of the play means that our responses must necessarily be mixed as well.

Leontes (Stephen Muterspaugh), ruler of Sicilia, is wildly jealous of his pregnant wife Hermione (Maryssa Wanlass). He suspects her of having an affair with his old friend Polixenes (David Everett Moore), king of Bohemia, who has been on an lengthy visit to Sicilia's court. In his madness Leontes twists everything into evidence of Hermione's unfaithfulness: when, at Leontes' bidding, Hermione urges Polixenes to extend his stay, Leontes sees both her willingness to make the request and Polixenes' acquiescence as confirmations of his suspicions.

Leontes (Muterspaugh), Hermione (Wanlass) and Polixenes (Moore) in "The Winter's Tale"

Leontes commands his advisor Camillo (Damon Seperi) to poison Polixenes; instead, Camillo warns Polixenes and flees with him to Bohemia—for Leontes, another confirmation that he is surrounded by disloyalty. When Hermione gives birth to a daughter, Leontes orders that the infant be abandoned in the wilderness and puts Hermione, accused of adultery, on trial for her life. Although the words of the Oracle proclaim her innocent, Leontes rejects them, and Hermione collapses and is announced to have died.

Sixteen years later the abandoned daughter, Perdita (Rosie Hallett), becomes engaged to Polixenes' son Prince Florizel (Davern Wright). Their engagement occasions Perdita's reunion with a now-repentant Leontes, a reconciliation between the estranged Leontes and Polixenes, and the discovery that Hermione did not die, but has been in hiding. It's hard to see this as a happy ending, though—by this point Leontes' brutal actions have forever forfeited our sympathies.

The actors were a talented and versatile ensemble, and director Rebecca J. Ennals and her creative design team cleverly pointed up the contrast between the sober, formal Sicilia and the colorful, joyful Bohemia. But another contrast—that between the sunny park setting and dark emotional world of the play—was perhaps too great for this outdoor "Winter's Tale" to fully succeed.

The Great German Songbook. Kindra Scharich, mezzo-soprano, with George Fee, piano. Seen Sunday, October 2, at the Noe Valley Ministry, San Francisco; produced by Lieder Alive!

To be without him is for me like the grave,Love is, of course, the great subject of the German lied. And Kindra Scharich seems to be at her considerable best when performing songs of longing and sorrow. She is an exceptionally subtle and communicative singer who can command an audience's rapt attention with hushed inwardness as well as dramatic intensity.

And the whole world is bitter.

My poor mind has gone mad,

My poor reason is dismantled,

My peace is gone, my heart is heavy,

I find it never and nevermore.

—Goethe, "Gretchen am Spinnrade" (Gretchen at the spinning wheel), from the musical setting by Franz Schubert

Kindra Scharich

This program was designed to be a kind of greatest hits of the lied, featuring works by a half-dozen composers spanning the 19th and early 20th centuries. It was an ideal introduction to lieder for someone like me, who is just beginning to appreciate the form. Hearing Scharich sing again some of the pieces she had sung during her SF Music Day preview of this program a week earlier helped me to discover new details in the words and musical settings. The way, for example, in which Schubert repeats the opening line of Goethe's poem to end the song "Gretchen am Spinnrade," leaving us with a feeling of uncertainty or suspension that echoes that of the lovelorn speaker (and creating a circular structure that brings to mind the turning of her wheel). Or the way that Liszt has the bell-like piano fall silent in the middle of "Ihr Glocken von Marling" (You bells of Marling):

If there was any minor issue with this superb program, it was that in the bright acoustic of the Noe Valley Ministry the volume of Fee's piano accompaniment never seemed to drop below mezzo-forte, even at those moments when Scharich was singing pianissimo. But this was a minor issue indeed.

Perhaps the peak moments of the concert were Scharich's performances of three Richard Strauss songs, the ardent "Zueignung" (Gratitude) and the quietly gorgeous "Morgen" (Morning) and "Allerseelen" (All Souls' Day), all of which simply glowed. Strauss's songs seem to be written for Scharich's rich vocal timbre and wide range; I very much hope that performing more of this composer is in her near-future plans.

This was the inaugural concert of Lieder Alive!'s 2016/17 Liederabend Series, which continues with Katherine Growdon, accompanied by Corey Jameson, performing Rilke songs by Schumann, Brahms, and Peter Lieberson on Sunday, October 30 at 5 pm in the Noe Valley Ministry. For more details about upcoming Liederabend concerts, please see the website of Lieder Alive!

No comments :

Post a Comment