Six months with Jane Austen: Mansfield Park and slavery III

Mansfield Park, an estate built on "the ruin and labour of others"

In The Country and the City, Raymond Williams compares the rural cottages of farming families with the great country houses that were built on the fruits of others' labor:

It isn't only that you know, looking at the land and then at the house, how much robbery and fraud there must have been, for so long, to produce that degree of disparity, that barbarous disproportion of scale. The working farms and cottages are so small beside them: what men really raise by their own efforts or by such portion as is left to them, in the ordinary scale of human achievement. What these 'great' houses do is to break the scale, by an act of will corresponding to their real and systematic exploitation of others. [1]Williams calls the great houses "visible triumphs over the ruin and labour of others...a visible stamping of power, of displayed wealth and command." He was speaking of the enclosure and expropriation of land formerly held in common by villages and small farmers during the 18th century and before, "land gained by killing, by repression, by political bargains." [2]

The wealth of many large landowners depended not only on expropriation at home, but on exploitation abroad: the trade in and the labor of slaves. In Mansfield Park we learn that Sir Thomas Bertram is the owner of an "Antigua estate." Antigua was one of the "sugar islands" of the West Indies, where virtually all the cultivable land had been converted to the production of sugar. Sugar cultivation was extraordinarily profitable, and by the early 19th century had led to the consolidation of vast plantations worked by armies of African slaves. Sugar was the main driver of the slave trade: about two-thirds of all the slaves brought from Africa to the New World were sent to areas of intensive sugar cultivation. [3]

As the owner of an Antiguan estate, Sir Thomas would have been understood by Jane Austen's contemporary audience to have been a slaveowner and a participant in the slave trade. And it is clearly from his sugar plantation that he derives the bulk of his wealth. In fact, it is highly likely that Sir Thomas was born on Antigua to a settler family. As Frank Gibbon has written,

One must not assume that sugar estates such as those on Antigua were owned by Englishmen born and bred who had somehow acquired them as speculative capitalists...Virtually every inch of the older West Indian islands was owned by West Indians, that is, by white settlers, relatives and descendents. [4]The implication is that Sir Thomas is an ex-colonist who moved to England in order to establish himself in British society. Mansfield Park has been built with the wealth produced by slaves.

Why does Sir Thomas go to Antigua?

Early in Mansfield Park we learn that "poor returns" and "some recent losses on his West India estate" make it "expedient [for Sir Thomas] to go to Antigua himself, for the better arrangement of his affairs." [5] While sugar plantations "were the largest privately owned enterprises of the age and their owners were among the richest of all men" [6], Sir Thomas discovers that his absentee ownership has led to problems on his plantation that threaten his wealth (and thus his social standing). What could have caused problems sufficiently severe to require Sir Thomas to return to Antigua in person?

The answer must necessarily be somewhat speculative—we are told only that Sir Thomas is dealing with "business"—but it probably relates to two main issues. The first is the abolition of the slave trade. Brian Southam has convincingly identified the time frame of Mansfield Park: the main action takes place between the fall of 1810, when Sir Thomas leaves for the West Indies, and the summer of 1813. This timing is significant because the British slave trade was abolished beginning in 1807, and the number of British naval ships stationed off the African coast to interdict slave ships was tripled (to 6) in 1810. [7]

With the supply of new slaves drastically diminished, it became more difficult to replace slaves who were worked to death, who were incapacitated or killed by injury, illness, or punishment, or who ran away to escape maltreatment. "Slave flight was the most common...form of slave resistance in Antigua," writes David Barry Gaspar. [8] It is likely that the managers left to oversee Sir Thomas's estate are having difficulty maintaining a sufficient labor force to run the plantation because of their harsh treatment of the slaves.

|

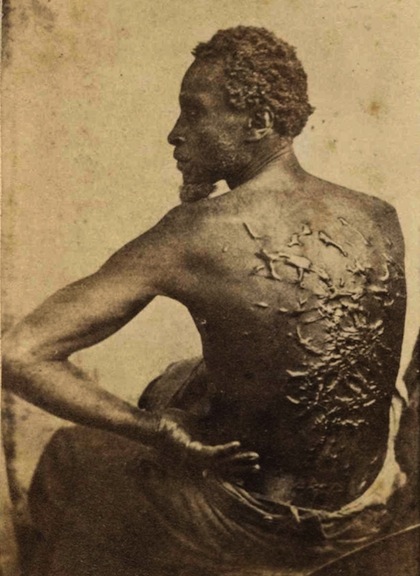

| Gordon, an escaped Mississippi slave whose back had been scourged. From the Matthew Brady studio, Washington, DC, ca. 1863. |

But Mansfield Park is a novel of parallels, and there are two in particular that are suggestive. Late in the novel Henry Crawford, suitor of Fanny Price, must travel to his Norfolk estate to deal with a problem that has arisen—more "business":

...It had been real business, relative to the renewal of a lease in which the welfare of a large and—he believed—industrious family was at stake. He had suspected his agent of some underhand dealing; of meaning to bias him against the deserving; and he had determined to go himself, and thoroughly investigate the merits of the case...He had introduced himself to some tenants whom he had never seen before; he had begun making acquaintance with cottages whose very existence, though on his own estate, had been hitherto unknown to him. This was aimed, and well aimed, at Fanny. It was pleasing to hear him speak so properly; here he had been acting as he ought to do. To be the friend of the poor and the oppressed! Nothing could be more grateful to her... [10]In Henry's absence, his agent has been acting in an "underhand" way with the laborers on his estate. Henry must intervene personally as a "friend of the poor and oppressed" in order to set things right. The parallel with Sir Thomas, who must travel to his Antigua plantation to investigate firsthand and set right the (probably brutal) actions of his agents, seems intended. [11]

Another parallel is with Mrs. Norris, Fanny's aunt, who in Sir Thomas's absence has been a cruel taskmistress to Fanny—another example of "ill-managed business":

"Fanny," said Edmund, after looking at her attentively, "I am sure you have the headache."Sir Thomas ultimately realizes his mistake in allowing Mrs. Norris to have any influence in his household: "Here had been grievous mismanagement." [13] Again, a parallel with the overseers' likely actions on the Antigua estate—the suggestion of overwork, cruelty, and indifference—seems deliberate.

She could not deny it, but said it was not very bad.

"I can hardly believe you," he replied; "I know your looks too well. How long have you had it?"

"Since a little before dinner. It is nothing but the heat."

"Did you go out in the heat?"

"Go out! to be sure she did," said Mrs. Norris: "would you have her stay within such a fine day as this? Were not we all out? Even your mother was out to-day for above an hour."

"Yes, indeed, Edmund," added her ladyship, who had been thoroughly awakened by Mrs. Norris's sharp reprimand to Fanny; "I was out above an hour. I sat three-quarters of an hour in the flower-garden, while Fanny cut the roses; and very pleasant it was, I assure you, but very hot. It was shady enough in the alcove, but I declare I quite dreaded the coming home again."

"Fanny has been cutting roses, has she?"

"Yes, and I am afraid they will be the last this year. Poor thing! She found it hot enough; but they were so full-blown that one could not wait."

"There was no help for it, certainly," rejoined Mrs. Norris, in a rather softened voice; "but I question whether her headache might not be caught then, sister. There is nothing so likely to give it as standing and stooping in a hot sun; but I dare say it will be well to-morrow. Suppose you let her have your aromatic vinegar; I always forget to have mine filled."

"She has got it," said Lady Bertram; "she has had it ever since she came back from your house the second time."

"What!" cried Edmund; "has she been walking as well as cutting roses; walking across the hot park to your house, and doing it twice, ma'am? No wonder her head aches."

Mrs. Norris was talking to Julia, and did not hear.

"I was afraid it would be too much for her," said Lady Bertram; "but when the roses were gathered, your aunt wished to have them, and then you know they must be taken home."

"But were there roses enough to oblige her to go twice?"

"No; but they were to be put into the spare room to dry; and, unluckily, Fanny forgot to lock the door of the room and bring away the key, so she was obliged to go again."

Edmund got up and walked about the room, saying, "And could nobody be employed on such an errand but Fanny? Upon my word, ma'am, it has been a very ill-managed business."

"I am sure I do not know how it was to have been done better," cried Mrs. Norris, unable to be longer deaf; "unless I had gone myself, indeed...I thought it would rather do her good after being stooping among the roses; for there is nothing so refreshing as a walk after a fatigue of that kind; and though the sun was strong, it was not so very hot. Between ourselves, Edmund," nodding significantly at his mother, "it was cutting the roses, and dawdling about in the flower-garden, that did the mischief."

"I am afraid it was, indeed," said the more candid Lady Bertram, who had overheard her; "I am very much afraid she caught the headache there, for the heat was enough to kill anybody. It was as much as I could bear myself. Sitting and calling to Pug, and trying to keep him from the flower-beds, was almost too much for me."

Edmund said no more to either lady; but going quietly to another table, on which the supper-tray yet remained, brought a glass of Madeira to Fanny, and obliged her to drink the greater part. She wished to be able to decline it; but the tears, which a variety of feelings created, made it easier to swallow than to speak.

Vexed as Edmund was with his mother and aunt, he was still more angry with himself. His own forgetfulness of her was worse than anything which they had done. Nothing of this would have happened had she been properly considered; but she had been left four days together without any choice of companions or exercise, and without any excuse for avoiding whatever her unreasonable aunts might require. [12]

A real-life model for Aunt Norris

"I thought it would rather do her good." The odious Mrs. Norris is constantly couching services that she demands from others in terms of the supposed benefits that will accrue to those who must perform the services on her behalf. In this she is echoing arguments notoriously put forward by some pro-slavery advocates. One in particular claimed that slavery benefits the slaves, "all of whom may be considered as rescued." He went on to assert

That this trade is carried on as much to the ease and comfort of those that are the subjects of it...as it is possible for human ingenuity to devise. That the ships employed in it, are so peculiarly constructed for the accommodation of the Negroes, as to be unsuitable for any other trade. That the opinion, which has been industriously propagated, of these ships being unequal to the numbers which were said to be crowded in them, is groundless;...That on the voyage from Africa to the West Indies, the Negroes are well fed, comfortably lodged, and have every possible attention paid to their health, cleanliness, and convenience.The author of these words was a man named Robert Norris. His views are held up to scorn in The History of the...Abolition of the British Slave-Trade, published in 1808 by Thomas Clarkson—one of Jane Austen's favorite authors; she wrote in 1813 that she had been "in love" with Clarkson. [15] Surely Mrs. Norris's last name cannot be a coincidence.

Hence it is, that the happiness and misery of Negroes, in the West Indies, depend almost totally on themselves...If he is industrious in his own concerns, and attentive to the interest of his superior, mild in temper, and tractable in disposition, he is entitled to indulgencies, which thousands, even in this country, would be happy to enjoy.—The habitations of the slaves, on every estate,...are, in general, comfortable and commodious;...this, with a comfortable night's rest, enables them to return with vigor to the next morning's work, which, however strange it may seem, is not so hard as that of most of the laboring poor in Britain. [14]

Real-life models for Sir Thomas Bertram and his sons

I wrote that Mansfield Park is a novel of parallels, and indeed there is a real-life parallel which may have informed Austen's portrait of Sir Thomas and his eldest son, Thomas. As Brian Southam discovered and Frank Gibbon has further researched, in 1760 Jane Austen's father George was appointed as a trustee of an Antiguan sugar plantation. [16] So Austen's immediate family were themselves involved in the slave economy. George Austen was named as a trustee on behalf of James Nibbs, who may have been one of his former students at Oxford. The two men were apparently quite close; in 1765 Austen asked Nibbs to stand as godfather for James Austen, his eldest son, who may have been named for Nibbs. (Nibbs may have named his second son, George, after Mr. Austen.)

Like Sir Thomas Bertram, James Nibbs came from Antigua to settle permanently in England. Nibbs had an eldest son, also named James, just as Sir Thomas's eldest son is also named Thomas. And James Nibbs Junior spent money extravagantly and became enmeshed in debt, just as the younger Thomas Bertram, "who feels born only for expense and enjoyment," does in Mansfield Park. [17]

In 1789 James Nibbs Senior took his son back with him to Antigua, just as Sir Thomas takes Thomas Bertram with him "in the hope of detaching him from some bad connexions at home." [18] James Junior had a devout younger brother who became a clergyman, just as does Thomas's younger brother Edmund. As Gibbon writes, "This story of the eldest son's prodigal waste of his family's Antiguan fortune and the steady piety of the younger son—his namesake—must have concerned the Rev. George Austen deeply and was undoubtedly a well-known and much-discussed family topic. [A portrait of James Nibbs Senior in the Austen household is mentioned in an 1801 letter of Jane's.] At any rate the coincidence with some of the events in Mansfield Park is remarkable." [19]

Next time: Emma and the fate of unmarried women

Last time: Mansfield Park and slavery II: Lord Mansfield and the antislavery movement

Other posts in the "Six months with Jane Austen" series:

- Favorite adaptations and final thoughts

- Persuasion and Austen's sailor brothers

- Persuasion and the British Navy at war

- Northanger Abbey and women writers and readers

- Mansfield Park and slavery I: Fanny Price and Dido Elizabeth Belle

- Pride and Prejudice and the marriage market

- Sense and Sensibility, inheritance, and money

- The plan

- Raymond Williams, The Country and the City, Oxford University Press, 1973, pp. 105-106.

- Williams, The Country and the City, pp. 97, 105-106.

- B. W. Higman, The sugar revolution. Economic History Review, Volume 53 Issue 2, 2000, pp. 213-236. Higman details the elements of the sugar revolution in the British Caribbean from the late 17th to the early 19th centuries, which include a rapid change from smallholdings raising diverse crops and employing indentured labor to large plantations devoted to sugar monoculture and relying on African slaves. By the 1750s the slave population on Antigua outnumbered the white population by ten to one (David Barry Gaspar, "To bring their offending slaves to justice": Compensation and slave resistance in Antigua 1669-1763, Caribbean Quarterly

Vol. 30 No. 3/4, 1984, pp. 45-59.) - Frank Gibbon, The Antiguan connection: Some new light on Mansfield Park. The Cambridge Quarterly, Volume 11 Issue 2, 1982, pp. 298-305.

- Jane Austen, Mansfield Park, Volume I Chapter iii; Chapter 3.

- R. W. Fogel, Without consent or contract: The rise and fall of American slavery, 1989, quoted in Higman, The sugar revolution, p. 223.

- Brian Southam, The silence of the Bertrams: Slavery and the chronology of Mansfield Park. Times Literary Supplement, 17 February 1995, pp. 13-14.

- Gaspar, "To bring their offending slaves to justice," p. 50.

- Austen, Mansfield Park, II. iii.; 21. This exchange has occasioned a great deal of comment. The silence is on the part of Fanny's cousins, rather than Sir Thomas himself (who is reported to be rather pleased with Fanny's interest in his "business affairs"). For extensive discussions of this passage, see Southam, The silence of the Bertrams, and George Boukulous, The politics of silence: Mansfield Park and the amelioration of slavery. NOVEL: A Forum on Fiction, Vol. 39 No. 3, 2006, pp. 361-383. I think Boukulous underestimates the extent of Jane Austen's abolitionist sympathies.

- Austen, Mansfield Park, III. x.; 41.

- I'm not the only one to whom this parallel has occurred; it is discussed at length in Boukulous, The politics of silence.

- Austen, Mansfield Park, I. vii.; 7.

- Austen, Mansfield Park, III. xvii.; 48.

- Robert Norris, A short account of the African slave trade, in Memoirs of the Reign of Bossa Ahadee, King of Dahomy, an Inland Country of Guiney, Lowndes, 1789, pp. 170-177; "rescued" comment, p. 156. See http://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/norris/menu.html

- Austen, letter to her sister Cassandra, 1813; see http://www.pemberley.com/janeinfo/auslet22.html#letter126: "I am as much in love with the author as I ever was with Clarkson..."

- Southam, The silence of the Bertrams; Gibbon, The Antiguan connection.

- Austen, Mansfield Park, i, ii.; 2.

- Austen, Mansfield Park, I. iii; 3.

- Gibbon, The Antiguan connection, p. 302.

No comments :

Post a Comment