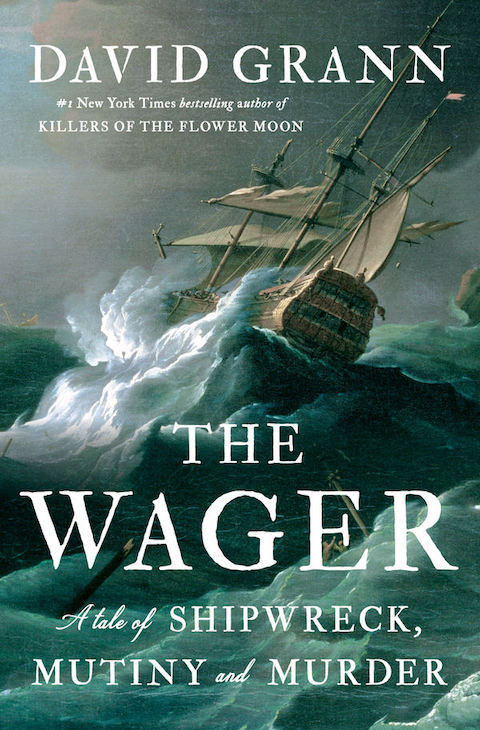

Cover of David Grann's The Wager (Doubleday, 2023), featuring "Ships in distress in a storm" (detail) by Peter Monamy (c. 1720-30), courtesy of Tate Britain. Cover image source: David Grann

The Anson expedition

Navigation during most of the age of sail was an approximate and error-prone business. It relied on inaccurate maps; dead reckoning using estimates of the ship's direction and speed using the position of the sun, a knotted rope and an hourglass; determination of latitude by the positions of the stars; and guesses about the vagaries of weather, wind, and currents. Clouds could mask the sun and stars, or a fierce storm could blow a ship hundreds of miles off course, not to mention pushing it onto rocks and shoals if it was near land, or sinking it outright.

Among the most hazardous seas in the world are those of Drake Passage/Mar de Hoces around Cape Horn at the southern tip of South America, where the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans meet. Wind and water are funneled between the southern tip of Patagonia and the northward-reaching Antarctic Peninsula, creating powerful currents, towering waves, and gale-force winds. Storms are frequent, with driving rain, sleet or snow falling more than 250 days out of the year. As if all that weren't enough, vessels must also avoid the many icebergs that dot the passage.

As told in David Grann's The Wager: A Tale of Shipwreck, Mutiny and Murder (Doubleday, 2023), in March 1741 Commodore George Anson's fleet of six British warships, plus an unarmed supply ship, approached Cape Horn. War had been declared by Britain against Spain in October 1739—the so-called War of Jenkins' Ear, named after the appendage of a British captain allegedly sliced off by a Spanish coast guard officer searching Jenkins' ship for smuggled goods in 1731. Anson's fleet had been ordered into the Pacific to raid coastal towns and disrupt shipments of silver to Spain (500 soldiers were on board for the purpose). Afterwards the fleet was to continue sailing north to Acapulco to capture a treasure galleon that sailed between Mexico and the Philippines twice a year. Clearly money and trade, and not Jenkins' ear, were the real causes of the war.

Portrait of George Anson, 1st Baron Anson, by Thomas Hudson, before 1748. Image source: National Maritime Museum

But Anson's fleet experienced a run of bad luck even before it reached Drake Passage. There had been months of delays before the fleet could sail. The ships required repair or refitting, and crews needed to be recruited, or impressed (i.e., kidnapped) into service. The fleet didn't sail from Portsmouth until mid-September 1740, and it made slow progress. It took three full months (including a one-week stopover on the Portuguese-held island of Madeira) to sail the roughly 5000 nautical miles to Santa Catarina (St. Catherine) Island and its ominously named town Desterro ("banishment"; it is now named Florianópolis) just off the the southern coast of Brazil.

From Santa Caterina Island, Anson intended to sail around Cape Horn into the Pacific during the Southern Hemisphere summer. But typhus ("ship fever") spread by body lice had been sweeping through the crews, killing around 150 men out of the 1800-odd on board all the ships. The fleet stayed berthed at Santa Caterina for a month, in part so that the ships could be fumigated. When the fleet departed in mid-January, there were further delays: a mast on the sloop HMS Tryal was damaged in a storm, forcing the fleet to put in at Port St. Julian further down the coast for repairs. Meanwhile the HMS Pearl was separated during the storm from the rest of the ships, was nearly captured by a pursuing Spanish naval squadron, and barely made it back to rejoin the fleet.

With all the delays the fleet did not pass through Le Maire Strait into Drake Passage until early March, as the fall storm season was approaching.

A view of the Streights Le Maire between Tierra del Fuego and Staten Land, from A voyage round the world in the years MDCCXL, I, II, III, IV [1740-44] by George Anson, Esq., Fifth Edition, 1749. Image source: HathiTrust

The crews were battling to make headway against furious waves, wind and sleet of the Cape when another disaster struck: scurvy, a debilitating disease caused by a lack of fruit, vegetables, and other sources of Vitamin C in the diet. The fleet's ships struggled to find enough men able to stand watch.

After five weeks of slow progress against the violence of the elements, the fleet became scattered. Two of the warships, HMS Pearl and HMS Severn, having lost sight of the other ships and with barely enough healthy men to operate the sails, turned around and headed back to the Atlantic. Before entering Drake Passage, Anson had set three rendezvous points off the coast of Chile with his captains in case their ships were separated. His flagship HMS Centurion did not reach the first rendezvous point, Socorro Island, until 8 May, two months after passing through Le Maire Strait. Its average speed on the roughly 1200-nautical-mile journey was less than one knot; the typical speed for Royal Navy ships at the time was around 3 knots. [1]

A few days before arriving at Socorro Island, the Centurion had sailed into a bay. A chart later published in Anson's account of the voyage noted "A Harbour where the Victualler belonging to Comm[odo]re Anson's Squadron anchor'd and found Refreshments." The "harbour" was the Golfo de Penas, and the refreshments may have been seal meat and fresh water. After taking on these supplies the Centurion sailed further north to Socorro, where it remained for two weeks, waiting for the other ships to arrive. None did.

Detail of chart showing the route taken by the Centurion. Noted on the chart is "A Harbour where the Victualler belonging to Comm[odo]re. Anson's Squadron anchor'd and found Refreshments," now known as the Golfo de Penas. "I[sle]. of Nostra Sig[nor]a de Socoro" and "Isles of Chiloe" are also identified. From A voyage round the world in the years MDCCXL, I, II, III, IV [1740-44] by George Anson, Esq., Fifth Edition, 1749. Image source: HathiTrust

The shipwreck of the Wager

One of those missing ships was HMS Wager, named after First Lord of the Admiralty Charles Wager. It was the first command of its captain, David Cheap, who had been promoted to the position during the voyage; at its start he had been first lieutenant on the Centurion.

Portrait of David Cheap by Allan Ramsay, c. 1748 (detail). Image source: The Guardian

Like the other ships, the Wager had been battered by the unrelenting storms. Being struck by large waves caused wooden hulls to flex and leak. The Wager's mizzenmast had been snapped by high winds, and many of the crew were too sick to stand watch.

Nonetheless it had managed to make it into the Pacific and was sailing northeast towards the rendezvous. But caught in another storm, the ship was pushed eastward towards the coast. When one of the sailors spotted land off the bow as the ship was being driven before the wind, the peril of their situation became immediately apparent. Captain Cheap ordered the Wager to turn completely around and sail south and west against the wind and away from land.

But it was too late. The ship had been driven into the Golfo de Penas (variously translated as the Gulf of Sorrows, Gulf of Tears, or Gulf of Punishment). There was land on three sides of the ship, and as they sailed southwest they were unknowingly heading straight for it. As later described by the Wager's 17-year-old midshipman John Byron, "the weather, from being exceeding tempestuous, blowing now a perfect hurricane, and right in upon the shore, rendered our endeavours (for we were now only twelve hands fit for duty) intirely fruitless." [2]

HMS Wager in extremis by Charles Brooking, 1744. Image source: Wikimedia Commons

On the heaving deck, Cheap fell through an open hatch and injured his left shoulder. He was carried to the surgeon's cabin and given a knockout dose of opium. If he had remained conscious it probably wouldn't have mattered. As Byron later wrote,

The night came on, dreadful beyond description. . .

In the morning, about four o'clock, the ship struck [a rock]. The shock we received upon this occasion, though very great, being not unlike a blow of a heavy sea, such as in the series of preceding storms we had often experienced, was taken for the same; but we were soon undeceived by her striking again more violently than before, which laid her upon her beam ends [i.e. listing far over to one side], the sea making a fair breach over her. . .

In this dreadful situation she lay for some little time, every soul on board looking upon the present minute as his last; for there was nothing to be seen but breakers all around us. However, a mountainous sea hove her off from thence; but she presently struck again, and broke her tiller. [3]

Now virtually unsteerable, the ship smashed into more rocks until it finally ran aground:

We now run in between an opening of the breakers, steering by the sheets and braces, when providentially we stuck fast between two great rocks; that to windward sheltering us in some measure from the violence of the sea. We immediately cut away the main and foremast; but the ship kept beating in such a manner, that we imagined she could hold together but a very little while. [4]

The hull was breached and water poured into the hold. Wedged between two rocks, though, the ship didn't completely sink, and its upper deck remained mostly above water.

At dawn the survivors crowded on deck saw that they were close to an island, but the rocks and breakers were dangerous and few of them could swim. Launching the four boats carried by the Wager—in descending order of size, a longboat, a cutter, a barge and a yawl—required lifting them over the gunwale. The longboat was trapped under debris, but using the other three boats the ship's junior officers eventually managed to get all the survivors ferried to the beach. It wasn't easy, because some of the crew on board decided that the moment had come to get blind drunk. In Byron's words,

The scene was now greatly changed; for many who but a few minutes before had shewn the strongest signs of despair, and were on their knees praying for mercy, imagining they were now not in that immediate danger, grew very riotous, broke open every chest and box that was at hand, stove in the heads of casks of brandy and wine as they were born up to the hatch-ways, and got so drunk, that several of them were drowned on board, and lay floating about the decks for some days after. . .The boatswain and some of the people would not leave the ship so long as there was any liquor to be got at. [5]

Close to 150 men survived the wreck, returning to the wreckage of the ship over the next few days to salvage supplies and the longboat.

Frontispiece of The narrative of the Honorable John Byron, Second Edition (1768). Image source: HathiTrust.org

But stranded on an uninhabited island with little food, the starving castaways soon formed into three factions: one, mainly consisting of the officers under Captain Cheap, continued to regard him as captain, and supported his plan to try to continue the mission by using the boats to reach the first rendezvous point at Socorro Island 200 nautical miles north. A second and much larger faction, led by the gunner John Bulkeley and including the boatswain John King, opposed Cheap: they wanted to sail south, navigate through the Strait of Magellan to the Atlantic Ocean, and try to make it back to Brazil (and ultimately Britain). A third faction, the seceders, moved away from the main group and set up their own camp a couple of miles away, occasionally stealing into the main camp to pilfer food, gunpowder, and other supplies. In the meantime the carpenter John Cummins worked to extend the damaged longboat so that it could hold more men and fitted it with masts and a deck, turning it into a schooner.

The mutiny

After five months, more than a third of the men on the island had died. Not all had starved: internecine squabbling had occasionally erupted in violence. Cheap had struck King with his cane and shot another man, the midshipman Henry Cozens, in the head for disobedience; Cozens took two weeks to die. Meanwhile a member of the seceders was found stabbed to death. The longboat was now ready, and it was clear that if the survivors didn't make it off the island soon, they would all die there. But Cheap persisted in his pointless plan to try to reach the uninhabited Socorro Island, where after all the time that had passed it was unlikely they would meet up with the rest of the fleet, and might find themselves stranded in the same situation.

Faced with Cheap's intransigence, in early October Bulkeley led a mutiny. The first idea was to arrest Cheap and take him back to England as a prisoner to put him on trial for Cozens' murder. But the difficulties of this plan soon became apparent, and instead Cheap and two of his allies were left behind, along with the seven of the seceders and the smallest and most damaged boat, the yawl. The remaining 81 men crowded into the three larger boats: 59 in the longboat, which was now christened the Speedwell, 12 in the cutter and 10 in the barge, a boat with 5 pairs of oars. The mutineers also took most of the remaining food and water.

Bulkeley's plan was for this makeshift flotilla to sail towards the Strait of Magellan, about 300 nautical miles to the south. But almost immediately it encountered a storm, and a sail on the Speedwell was torn. The boats had to put into what is now called Speedwell Bay, just a mile west of the castaway's camp, to wait out the storm and repair the sail. Bulkeley sent 10 volunteers in the barge back to the camp they'd just left to gather up additional canvas (sailcloth had been used to make tents, most of which were now abandoned). But two of the volunteers, Byron and midshipman Alexander Campbell, had second thoughts about the mutiny. They decided to rejoin Cheap's group, and convinced the other 8 men to do so as well.

The voyage of the Speedwell

Bulkeley's group, now with only two boats, sailed on. The Speedwell was so overloaded with men and supplies that its stern cleared the water by inches. And while it was possible to shelter from the elements under the deck, there wasn't enough room to lie down full length anywhere on board. The keel was deep enough that the boat couldn't get too close to shore without the danger of running aground or striking a rock. The smaller cutter had a shallower draft, and so it could be sent to shore on foraging expeditions. But one night in early November after most of the cutter's crew had climbed into the Speedwell to try to sleep, the rope tying the cutter to the Speedwell broke, and the cutter was swept away with a man on board.

Now the Speedwell, jammed with 70 men, was even more crowded, and there was no way for men to go ashore other than to swim. The boat wallowed so low in the water that 11 men decided to take their chances on land and swam to shore (in Grann's account, probably based on Bulkeley's; more likely, as with Cheap's decision to remain on Wager Island, it was a forced choice). The Speedwell continued sailing.

On 10 November the Speedwell found the mouth of the strait. But just as it was about to enter in rough seas a wave struck the boat, swamping it. It heeled so far over that it lay on its side, with water pouring in. With men clinging desperately to anything they could hold onto, the boat miraculously righted itself and was able to make it into the strait, where the winds and water were calmer than in the open ocean.

Detail of chart showing the Strait of Magellan. From A voyage round the world in the years MDCCXL, I, II, III, IV [1740-44] by George Anson, Esq., Fifth Edition, 1749. Image source: HathiTrust

The boat had escaped disaster, barely, but the situation remained dire. The men were starving and the strait, with many branching channels, was difficult to navigate. On 24 November, after sailing southeast in the strait for two weeks, the men became disoriented and unsure if they had truly found the right passage. It was decided to turn back—a costly decision, as eventually they realized that they had been following the correct route all along. Meanwhile, men had begun to die, their bodies dumped unceremoniously into the water to make more room for the survivors on board. The Speedwell turned around again, and headed back through the strait.

Finally, on the night of 10-11 December they sailed through a dangerously narrow passage in the dark. The next morning they found themselves in a broad bay facing Cape Virgenes, or the Cape of the Virgins (named after the 11,000 virgin martyrs of St. Ursula). Nearly 10 months earlier the fleet had passed it heading south on its way to Le Maire Strait.

Ten months previously: Cape Virgin Mary at the north entrance of Magellans Streights, from A voyage round the world in the years MDCCXL, I, II, III, IV by George Anson, Esq., Fifth Edition, 1749. Image source: HathiTrust

Somehow after two months in the jury-rigged longboat, navigating by guess, the men had made it 600 nautical miles to the eastern mouth of the strait and the Atlantic Ocean.

But their situation was still perilous: they were virtually out of food and water, and any parties sent ashore to forage would risk capture, because the coast of Patagonia was held by the Spanish. The nearest neutral territory was the port of Rio Grande in Brazil, 1800 nautical miles north. They had come a long way, but had three times as far still to go. They set sail up the coast.

About a week later they sailed into a small bay, Puerto Deseado (Port Desire), where there was a seal rookery. The water was shallow and the men were able to wade ashore and slaughter a number of seals. While this was apparently their salvation, gorging themselves on seal meat and blubber after being on starvation rations for months sickened the crew, and two men died.

Further up the coast a few weeks later, the seal meat having run out, it was decided that another hunting party would be sent ashore at Freshwater Bay, near what is now Mar del Plata, Argentina. This time the water was not shallow; the men who went ashore had to swim through breakers, and one drowned. Guns were sent after them lashed to empty barrels. The men shot some seals and a horse, which turned out to be branded. Concerned about being discovered, six of the men swam back to the Speedwell. No sooner had they made it to the boat than a storm blew up and drove it away from land. The rest of the foraging party, eight men, were left stranded on shore. That night the Speedwell's rudder broke, making it difficult to steer. It was decided that returning for the men on shore was too dangerous, and so the Speedwell sailed on.

On 28 January 1742 the boat limped into the port of Rio Grande with what remained of its crew, just 30 gaunt and haggard survivors from the 150 men who had been shipwrecked on Wager Island 259 days earlier.

Detail of chart showing the Strait of Magellan, Port Desire, and Rio Grande. From A voyage round the world in the years MDCCXL, I, II, III, IV by George Anson, Esq., Fifth Edition, 1749. Image source: HathiTrust

Now the men faced another peril: a possible trial for mutiny. Accusations and recriminations flew, and attempts were made to steal and destroy Bulkeley's log from the journey. A ship's officer, Lieutenant Robert Baynes, sailed for England in March in an attempt to exculpate himself and cast blame on the others. Months later Bulkeley and Cummins followed; on their arrival in Portsmouth they were promptly arrested and imprisoned. Released two weeks later, they awaited trial.

Bulkeley had managed to keep his journal, and wrote out a version of events that highlighted Cheap's erratic decisionmaking and violence, and claimed that the captain had decided of his own free will to remain on the island. Bulkeley expanded these notes into a book-length manuscript, which was published six months after his return and was so popular that it went into a second printing. Bulkeley seemed to have won in the court of public opinion, at least for the moment. But the story was far from over.

The fate of the men on Wager Island

After Byron, Campbell, and the other sailors on the barge rejoined Cheap's group on Wager Island, Cheap revived the plan to try to sail to the first rendezvous point. Joined by the surviving members of the third faction, the group consisted of 19 men in all. In mid-December 1741 they packed all their supplies and themselves into the barge and yawl, and began sailing north. But only an hour into the journey a storm broke and waves began to swamp the boats. To lighten their load, the famished men tossed most of their supplies, including their precious food, overboard.

After sheltering on land overnight, they pressed on, and about two weeks after leaving Wager Island they tried to pass the headland that marked the north entrance of the Gulf of Punishment. But the winds and waves were so strong they could not beat around it, being pushed back into the gulf at every attempt. Exhausted, they landed on the leeward side of the cape and shot a seal, on which they feasted. But that night high winds and waves overturned the yawl at anchor and it sank, drowning one of the two men aboard.

Now the 18 surviving men had only the barge, which couldn't hold that many. Four marines were chosen to remain behind. They were given guns and a frying pan. The 14 men in the barge made another attempt to round the cape, but were beaten back yet again. At this point it was clear to them all that it was fruitless to continue. They returned to the beach where they had left the marines, but apart from an abandoned gun—an ominous indication of the fate of the marines—there was no sign of them. The men in the barge decided to return to Wager Island.

In early March, shortly after their return to their old camp (Grann says "a few days"), men in canoes landed on Wager Island. They identified themselves as members of a tribe from the north, the Chono. They agreed to guide the men to Chiloé Island, which was located about 100 miles north of Socorro Island, and was occupied by the Spanish. In exchange the stranded men agreed to give the Chono the barge once they'd arrived at their destination.

They rowed out again, following the coast. But when most of the group had gone ashore to forage for food, six of the castaways rowed off in the barge, leaving the rest behind. The remainder, guided by the Chono tribesmen, continued in the canoes and overland on foot. It took several months, but four of the castaways finally reached Chiloé Island: Byron, Campbell, the marine lieutenant Thomas Hamilton, and Cheap.

After spending a few days recuperating from the voyage in an indigenous village they were seized by Spanish soldiers and became prisoners of war. They were eventually sent to a jail in Valparaiso on the mainland, and then on to Santiago, where they were paroled, but unable to leave. Two years later, with hostilities between Britain and Spain damped down, the countries agreed on a prisoner exchange. Once word reached Santiago, the men were told that they were free to go, and given passage on a ship headed for Spain. (Campbell instead decided to travel overland to Buenos Aires, a hazardous journey, and embark from there.) In April 1745 (according to Grann) they landed at Dover, and headed to London to confront Bulkeley and the other mutineers.

Amazingly, they were not the last survivors of the Wager to make it back to England. And the story of the fate of the Centurion and the rest of the Anson expedition in the Pacific is also astonishing. In The Wager, David Grann relates this multi-stranded, harrowing and sometimes gruesome narrative vividly and (odd though it sounds) entertainingly.

For the taste of some, perhaps too vividly and entertainingly: direct speech is reported ("Rouse out, you sleepers! Rouse out!" (p. 27)), other imaginary details are described ("Bulkeley. . .felt a shiver of recognition" (p. 194)), and free indirect style is liberally applied ("Cheap wanted to make one final attempt to round the cape. They were so close, and if they made it he was sure that his plan would succeed" (p. 190)).

If this sort of extrapolation—or fictionalized departure—from the sources drives you nuts, you'd be well advised to avoid The Wager. The same is true if small inconsistencies are bothersome. To take just a few examples:

- The Speedwell enters the Strait of Magellan with 59 men on board: the 81 who left Wager Island, minus the 10 who rejoined Cheap, the man lost in the cutter and the 11 sent to shore. After two weeks in the strait, "they were dying. Among the casualties was a sixteen-year-old-boy named George Bateman. 'This poor creature starved, perished, and died a skeleton,' Bulkeley wrote. . .One twelve-year-old. . .boy's misery ended only when 'heaven sent death to his relief'" (pp. 183-84). With at least two dead, there are now at most 57 men on board. But a few pages later, "Bulkeley and the fifty-eight other castaways on the Speedwell were back on course" (p. 192).

- At Freshwater Bay, "the boatswain, King, the carpenter, Cummins, and another man. . .leapt into the water. Galvanized by the sight, eleven others, including John Duck, the free Black seaman, and Midshipman Isaac Morris, followed. One marine. . .drowned within twenty feet of the beach" (p. 191). So fourteen men leave the boat, and thirteen make it to shore. A few hours later, "Cummins, King, and four others swam back to the boat. . .But a squall drove the Speedwell out to sea, and eight men, including Duck and Morris, were left stranded on land" (p. 196). Shouldn't that be seven men? Or did fifteen men, and not fourteen, leap into the water?

- When Cheap and the other castaways left behind on Wager Island make their attempt to reach the first rendezvous point in mid-December 1741, it takes them nine days to reach the northern headland of the Golfo de Penas. "A few days later" (Day 14?) they make their first attempt to row around the cape. Beaten back, a couple of days later they make a second attempt, which also fails. The yawl sinks overnight, and the decision is made to leave the four marines behind. Grann's description is a bit vague, but by my count we've reached Day 18 or thereabouts. The next sentence reads, "Six weeks after Cheap and his party fled Wager Island, they reached the cape for the third time" (p. 190). We've jumped from Day 18 to Day 42 with no explanation. If the beach where the marines were abandoned was a few hours' sailing from the headland (as is strongly implied), why does it take the men in the barge 24 days, or more than three weeks, to reach it once more?

- After the abandonment of the marines and the third failed attempt to row around the cape, fourteen men return to Wager Island in the barge. "Days after" their return several Chono tribesmen arrive. "At that time, Cheap, Byron, and Hamilton were stranded with ten other castaways" (p. 222); nothing is mentioned about the fourteenth man. In early March all the survivors depart the island with their guides. Soon after six of the men steal the barge and sail away. Grann writes of the men left behind, "During the journey, a castaway died, leaving only 'five poor souls'" (p. 223). If thirteen castaways left Wager Island, six men stole the barge, and one man died, shouldn't six "poor souls" remain? Or did only twelve men leave Wager Island? In which case, why is Grann silent about the fates of the other two men?

These are the kinds of small errors and omissions that used to be caught by copy editors. But copy editors don't seem to exist any more, even at large publishing houses like Doubleday.

Coda: John Byron, The Narrative, and his grandson

On returning to England, John Byron was considered a hero and, at 23, was given command of his own ship, the frigate HMS Syren. In 1748 he married his cousin Sophia Trevanion; although Byron was often at sea, Sophia gave birth to nine children, of whom six survived infancy.

Portrait of Captain John Byron by Joshua Reynolds, 1748. Image source: Nottingham City Museums and Galleries

John Byron commanded the expedition that laid claim to the Falkland Islands for Britain, and he circumnavigated the globe in the frigate Dolphin, which had a copper-sheathed hull that increased its speed and seaworthiness. (The Dolphin returned to England in May 1766, 22 months after its departure—the fastest circumnavigation at that time.) In 1768 Byron published The Narrative of the Honourable John Byron (Commodore in a Late Expedition round the World), Containing an Account of the Great Distresses Suffered by Himself and his Companions on the Coast of Patagonia, from the Year 1740, till their Arrival in England, 1746, containing a detailed description of the wreck of the Wager. Having risen to the rank of Vice Admiral of the White, Byron died in April 1786 at the age of 62.

His eldest son John, known as Jack (or "Mad Jack") had a far less disciplined character. As an army officer in 1778 at age 21 he seduced Amelia, Lady Carmathen, a beautiful and wealthy 23-year-old mother of three; a few months later they ran off together. Amelia was divorced by her husband on 31 May 1779; heavily pregnant, she married Jack Byron just over a week later on 9 June, and gave birth to a daughter a month later. Only one of their children survived infancy: Augusta, born in 1783.

Amelia died in January 1784; she was only 29. A year later in Bath, Jack met, courted and married the 20-year-old Scottish heiress Catherine Gordon. In 1788 she gave birth to a son, George Gordon, who later became the renowned poet Lord Byron (and, it is believed, had a daughter, Elizabeth, with his half-sister Augusta).

Portrait of Byron at age 24 by Thomas Phillips, 1812. Image source: Nottingham City Museums and Galleries

In Don Juan, Canto the Second (1819), Byron writes a mock-epic shipwreck scene that draws many details from his grandfather's account of the Wager disaster, including:

The broken tiller:

At one o'clock the wind with sudden shift

Threw the ship right into the trough of the sea,

Which struck her aft, and made an awkward rift,

Started the stern-post, also shatter'd the

Whole of her stern-frame, and, ere she could lift

Herself from out her present jeopardy,

The rudder tore away: 'twas time to sound

The pumps, and there were four feet water found. [6]

The ship nearly capsizing:

. . .The wind blew fresh again: as it grew late

A squall came on, and while some guns broke loose,

A gust—which all descriptive power transcends—

Laid with one blast the ship on her beam ends.

There she lay motionless, and seem'd upset;

The water left the hold, and wash'd the decks,

And made a scene men do not soon forget. . . [7]

The masts being taken down:

Immediately the masts were cut away,

Both main and mizen; first the mizen went,

The main-mast follow'd: but the ship still lay

Like a mere log, and baffled our intent.

Foremast and bowsprit were cut down, and they

Eased her at last (although we never meant

To part with all till every hope was blighted). . . [8]

And the unruly crew breaking into the stores of liquor:

. . .even the able seaman, deeming his

Days nearly o’er, might be disposed to riot,

As upon such occasions tars will ask

For grog, and sometimes drink rum from the cask.

. . .the crew, who, ere they sunk,

Thought it would be becoming to die drunk. [9]

Eight decades after John Byron's horrific near-fatal experience, from which he emerged only through almost superhuman endurance and the resilience of youth, it would become satirical grist for his grandson's greatest poem.

Next post in this series:

- For more information, omitted from Grann's account, about connections between the Anson expedition and the slave trade, please see the post The Wager and slavery.

- Morgan Kelly and Cormac Ó Gráda, "Speed under sail during the early industrial revolution (c. 1750–1830)." The Economic History Review 72 (2019), pp. 459–480. https://doi.org/10.1111/ehr.12696

- John Byron, The Narrative of the Honourable John Byron (Commodore in a Late Expedition round the World), Containing an Account of the Great Distresses Suffered by Himself and his Companions on the Coast of Patagonia, from the Year 1740, till their Arrival in England, 1746 (1768), p. 9. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433059336309&seq=29

- John Byron, pp. 9–11. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433059336309&seq=28&view=2up

- John Byron, p. 14. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433059336309&seq=34&view=2up

- John Byron, pp. 15–16. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433059336309&seq=34&view=2up

- [George Gordon, Lord Byron,] Don Juan, Canto II, Stanza XVII: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.c041905176&seq=146&view=1up

- Don Juan, Canto II, Stanzas XXX and XXXI: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.c041905176&seq=148&view=1up

- Don Juan, Canto II, Stanza XXXII: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.c041905176&seq=149&view=1up

- Don Juan, Canto II, Stanza XXXIII, XXXIV, and XXXV: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.c041905176&seq=150&view=2up