The Thrilling Adventures of Lovelace and Babbage

Sydney Padua, The Thrilling Adventures of Lovelace and Babbage (Pantheon, 2015). Image source: The Beat, the blog of comics culture

It's an uncanny feeling to open a book and have the sense that it was written specifically for you. I had that feeling almost continuously while reading Sydney Padua's The Thrilling Adventures of Lovelace and Babbage (Pantheon, 2015).

Augusta Ada Byron King, Lady Lovelace, was the daughter of Anne Isabella (Annabella) Milbanke and the poet Lord Byron. Ada's mother separated from Byron after a year of marriage and raised her daughter to have an anti-Byronic cast of mind: rational, scientific, mathematical. Before their marriage Byron called Annabella "my Princess of Parallelograms"; afterwards he called her the "Mathematical Medea."

Annabella Milbanke by George Hayter, 1812, three years before her marriage to Byron. Image source: Wikimedia Commons

Lady Byron's plan to suppress her daughter's imagination through rationality, however, was destined to be foiled by how truly strange math is. One of Ada's tutors, William Frend (who had also taught Annabella as a young woman), refused to believe in the existence of negative numbers, because how could anything be less than nothing? Numbers can also be irrational (if they can't be expressed as a ratio of two integers, such as π) and even imaginary (if they involve the square root of a negative number, such as i, where i2 = –1). Ada outpaced most of her teachers.

Ada Byron at 16, 1832, artist unknown. Image source: Wikimedia Commons

In June 1833, at age 17, Ada met the mathematician and inventor Charles Babbage, then the Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at Trinity College, Cambridge. [1]

Engraving of Charles Babbage, 1832 (age 40) by John Linnell, published by Paul and Dominic Colnaghi & Co., 1 January 1833. Image source: National Portrait Gallery NPG D16124

In a letter dated Friday 7 June 1833 to Ada's tutor Dr. William King, Lady Byron wrote:

Ada was more pleased with a party she was at on Wednesday [5 June], than with any of the assemblages in the grand monde [Ada had been presented at court on 10 May and had since attended several court balls]—she met there a few scientific people—amongst them Babbage, with whom she was delighted—. . .Babbage was full of animation—and talked of his wonderful machine (which he is to shew us) as a child does of its plaything. [2]

Babbage was working on a mechanical calculator he called the Difference Engine, and had produced a small working prototype which he demonstrated for Ada and her mother. In a letter to King on Friday 21 June, Lady Byron wrote,

We both went to see the thinking machine (for such it seems) last Monday [17 June]. It raised several Nos. to the 2nd & 3rd powers, and extracted the root of a Quadratic Equation.—I had but faint glimpses of the principles by which it worked.

Sophia Frend, William's daughter, also attended the demonstration and later wrote that in contrast to Lady Byron, "Miss Byron, young as she was, understood its working, and saw the great beauty of the invention." [3]

"Portion of Babbage's Difference Engine," Harper's New Monthly Magazine, Vol. XXX, No. CLXXV, December 1864, p. 34, digitized from the collections of the University of California Berkeley. Image source: HathiTrust.org

In 1834, with the Difference Engine still far from completion, Babbage began working on an even more sophisticated device he called the Analytical Engine. He envisioned a punchcard control system that would specify the mathematical operations to be performed. The principle was similar to the way punchcards controlled the mechanical Jacquard looms used to weave complex patterned cloth (and which had been the targets of the Luddite weavers who had been thrown out of work).

Portion of the mill of the Analytical Engine with printing mechanism, designed by Charles Babbage and under construction at the time of his death, London, 1834-1871. (Trial model). Image source: Science Museum Group Collection Online

In 1835 Ada Byron married William King (a different William King than her tutor). Thanks to Ada's family connections—her mother was the cousin of the prime minister, Lord Melbourne—William was created the first Lord Lovelace in 1838, and so Ada became Lady Lovelace. [4]

Ada King by Margaret Carpenter, 1836. Image source: Wikimedia Commons

Motherhood, family concerns and social demands took Ada away from her mathematical studies, but after the birth of her third child in four years of marriage she was eager to resume them. She began a correspondence with the mathematician Augustus De Morgan, husband of Sophie Frend and friend of Charles Babbage. De Morgan later wrote to Lady Byron:

But I feel bound to tell you that the power of thinking on these matters which Lady L. has always shewn from the beginning of my correspondence with her, has been something so utterly out of the common way for any beginner, man or woman. . .Had any young beginner, about to go to Cambridge, shewn the same power, I should have prophesied first that his aptitude at grasping the strong points and the real difficulties of first principles. . .would have certainly made him an original mathematical investigator, perhaps of first-rate eminence. [5]

In 1840 Babbage gave a lecture on the Analytical Engine in Turin; mathematician (and future prime minister of Italy) Luigi Menabrea attended, and two years later published an article describing the machine in the journal Bibliothèque universelle de Genève—the first publication about the Analytical Engine.

L.-F. Menabrea, "Notions sur la machine analytique de M. Charles Babbage." Bibliothèque universelle de Genève, Nouvelle Série, tome XLI (Sept.-Oct. 1842), pp. 352-376. Image source: HathiTrust.org

Shortly after it appeared Ada began working on a translation of Menabrea's article; her translation was published the following year in Richard Taylor's Scientific Memoirs, Vol. III, Part XII. The 25-page-long "Sketch of the Analytical Engine invented by Charles Babbage, Esq." by Menabrea was accompanied by 41 pages of "Notes by the Translator," signed A.A.L. (for Augusta Ada Lovelace). [6]

Ada shared the notes with Babbage as she was writing them, but was understandably exasperated if he made revisions without her agreement. As her drafts were traveling back and forth between their houses she wrote him, "I am much annoyed at your having altered my Note. You know I am always willing to make any alterations myself, but that I cannot endure another person to meddle with my sentences." [7]

A.A.L., "Notes by the Translator" [to accompany L. F. Menabrea, "Sketch of the Analytical Engine invented by Charles Babbage, Esq." (pp. 666-690)] in Richard Taylor, ed. Scientific Memoirs, Selected from the Transactions of Foreign Academies of Science and Learned Societies, and Foreign Journals, Vol. III, Part XII (Aug. 1843), pp. 691-731. Image source: HathiTrust.org

Ada's notes to Menabrea's article include instructions for the calculation of Bernoulli numbers by the Analytical Engine, an algorithm that has been called the first computer program.

Sydney Padua, The Thrilling Adventures of Lovelace and Babbage (Pantheon, 2015), p. 25 (detail). Image source: Goodreads

Ada's copious Notes, which often themselves have footnotes, were clearly an inspiration for the format of Thrilling Adventures. Marketed as a graphic novel, it's a hybrid mix of graphics and text: virtually every page features extensive footnotes, and, in a droll touch, the footnotes have even more extensive endnotes (which, like Ada's "Notes by the Translator," also have footnotes). The fascinating dual subjects of the book deserve that extensive scholarly apparatus, even if its purpose is partially parodic. As someone who writes blog posts whose footnotes are sometimes longer than the post itself, I felt an immediate sympathy. [8]

Sydney Padua, The Thrilling Adventures of Lovelace and Babbage (Pantheon, 2015), p. 22; right-click to enlarge. Image source: Science Museum Group Journal

In her Notes Ada had made a huge leap; she'd recognized that the Analytical Engine could perform operations on any data to which an algorithm could be applied:

The operating mechanism. . .might act upon other things besides number, were objects found whose mutual fundamental relations could be expressed by those of the abstract science of operations, and which should be also susceptible of adaptations to the action of the operating notation and mechanism of the engine. [9]

With this insight Ada anticipated the development of the modern computer a century later.

Ada Lovelace, daguerreotype by Antonie Claudel, ca. 1843. Image source: Wikimedia Commons

Babbage teased Ada (who was slight of build) by calling her a fairy; in a letter to him as she was working on the Notes she embraced that supernatural identity:

That brain of mine is something more than merely mortal; as time will show; (if only my breathing & some other etceteras do not make too rapid a progress towards instead of from mortality). Before ten years are over, the Devil’s in it if I haven’t sucked out some of the life-blood from the mysteries of this universe, in a way that no purely mortal lips or brains could do. [10]

It was not to be. Instead of plumbing the mysteries of the universe, Ada used her mathematical talents to develop a betting system for horse racing. Initially both her husband and Babbage joined her in placing bets using the system. However, when it became clear that the system didn't work, the men stopped using it. Ada continued, disastrously, and fell deeply in debt; she secretly pawned her jewels, twice, and had to ask her mother to redeem them.

As the reference to her breathing in the letter above suggests, Ada's health was also not robust. Victorian doctors prescribed opium in various forms (pills or dissolved in alcohol as laudanum) for a host of maladies, including to ease the breathing difficulties whose actual cause was likely the thick pall of London coal and wood smoke. The inhibition-lowering properties of opium may have played a role in her reckless gambling, although high-stakes betting seems to have been endemic among the British upper classes.

Sydney Padua, The Thrilling Adventures of Lovelace and Babbage (Pantheon, 2015), p. 28 (detail). Image source: Pinterest

Ada was also frequently in pain, and in mid-1852 she was diagnosed with terminal cancer. Perhaps as a memento, her husband commissioned a final portrait of her by the artist Henry Wyndham Phillips; despite her condition, she sat for the painting throughout August. On 13 August Lord Lovelace recorded in his diary that "the suffering was so great that she could scarce avoid crying out"; although she was in agonizing pain, "she sat at the piano some little time so that the artist could portray her hands." [11]

Daguerreotype by an unknown photographer of a portrait of Ada Lovelace by Henry Wyndham Phillips, 1852 (detail). Image source: Bodleian Library

Babbage was forbidden by Lady Byron from visiting Ada after mid-August. After months of suffering Ada died on Saturday 27 November 1852, two weeks before her 37th birthday.

In the decades following the publication of Ada's article, Babbage made few advances toward building the Analytical Engine. Progress remained stalled pretty much as described by an anonymous article entitled "Addition to the memoir of M. Menabrea on the analytical engine" published in The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science in September 1843 (immediately after the publication of Ada's translation and Notes in Scientific Memoirs). The article, almost certainly written by Babbage, states:

The present state of the Analytical Engine is as follows:—

All the great principles on which the discovery rests have been explained, and drawings of mechanical structures have been made, by which each may be carried into operation. . .

Mechanical Notations have been made both of the actions of detached parts and of the general action of the whole, which cover about four or five hundred large folio sheets of paper.

The original rough sketches are contained in about five volumes.

There are upwards of one hundred large drawings. [12]

The plans for the Analytical Engine were clearly of daunting complexity, and it's no wonder that they were not realized. Babbage was a spiky personality and an eccentric polymath, and spent a good deal of time and energy not only on other projects, but pursuing cantankerous campaigns against street musicians, hoop-rolling, and other public nuisances. At the time of his death in 1871 a partial model of the Analytical Engine was still incomplete (see above).

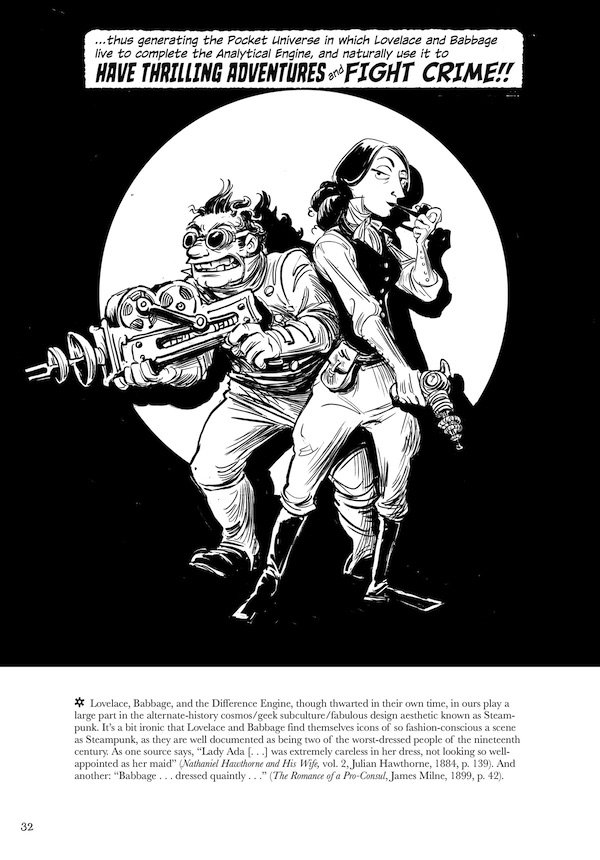

In 2009 over a beer at a pub animator Sydney Padua was commissioned by Suw Charman-Anderson, who was planning the first annual Ada Lovelace Day, to produce a short web comic on Ada's life. In the preface to Thrilling Adventures Padua writes, "Lovelace died young. Babbage died a miserable old man. There never was a gigantic steam-powered computer. This seemed an awfully grim ending for my little comic. And so I threw in a couple of drawings at the end, imagining for them another, better, more thrilling comic-book universe to live on in" (p. 7).

Sydney Padua, The Thrilling Adventures of Lovelace and Babbage (Pantheon, 2015), p. 32. Image source: The Beat, the blog of comics culture

Those "couple of drawings" grew into the 300-page Thrilling Adventures. Each adventure takes place in a steampunk alternate universe in which a full-scale Analytical Engine has been built. Over the course of Thrilling Adventures Lovelace and Babbage encounter the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Queen Victoria, the novelist George Eliot, the logician George Boole, and the world of the Alice stories written by Lewis Carroll. [13]

Padua's Thrilling Adventures of Lovelace and Babbage is an exhilaratingly witty and imaginative journey through computer history and the Victorian scientific, political, and literary worlds. It is also an illuminating portrayal of Ada Lovelace, whose pioneering work, while still underappreciated, has begun to receive the attention it deserves. The annual Ada Lovelace Day, on the second Tuesday in October, is now a global grassroots celebration of the achievements of women in science, technology, engineering and mathematics; in 2023 the 15th annual Ada Lovelace Day will take place on 10 October. [14]

And in the alternate universe of Thrilling Adventures, there is a happy ending for Lovelace and Babbage, as the Analytical Engine is completed and they can spend many contented hours in conversation and calculation:

Sydney Padua, The Thrilling Adventures of Lovelace and Babbage (Pantheon, 2015), pp. 286-287. Image source: Mark Riedl, Medium.com

- Lucasian Professors have included Isaac Newton (1669–1702) and Stephen Hawking (1979–2009). ^ Return

- Quoted on p. 299-300 in Velma R. Huskey and Harry D. Huskey, "Lady Lovelace and Charles Babbage," Annals of the History of Computing, Vol. 2, No. 4, pp. 299-329, Oct.-Dec. 1980, doi: https://doi.org/10.1109/MAHC.1980.10042 (subscription or institutional access required). ^ Return

- Quoted in Huskey, p. 300. ^ Return

- William Lamb, Lord Melbourne, was the widower of Caroline Lamb, who had been the lover of Ada's father, Lord Byron, before his marriage to Annabella. For details, see An Elegant Madness: High Society in Regency England. ^ Return

- Quoted in Huskey, p. 326. ^ Return

- Notes A - F are signed A.A.L.; Note G is signed A.L.L., likely a typographical error for A.A.L. The suggestion for signing the notes with her initials came from Ada's husband. ^ Return

- Quoted in Huskey, p. 316. ^ Return

- In Thrilling Adventures Sydney Padua offers the following footnote: "Lovelace added seven footnotes to her translation of Menabrea's Sketch of the Analytical Engine; they are a little over two and a half times longer than the original paper. . .Together they take up 65 pages of the September 1843 edition of Taylor's Scientific Memoirs, a journal dedicated to publishing English translations of work from continental Europe" (p. 25).

This isn't quite right. Lovelace's "Notes by the Translator," lettered A. to G., are endnotes, not footnotes (Ada also added footnotes on 10 of the original article's 25 pages); the notes are two-thirds again as long as the original article (41 pages of notes to 25 pages of article), not over two and a half times longer; together with the original paper they take up 66, not 65, pages of Vol. III of Taylor's Scientific Memoirs, each volume of which was published in parts, not "editions"; and finally, Part XII of Scientific Memoirs, according to the Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 4, No. 28 (Jun. - Dec., 1843), p. 19, and Ada's correspondence as quoted in Huskey, was published in August, not September, 1843.

There are some other minor errors as well. In the first footnote on p. 22 (see above) Padua writes "Babbage was forty-two and Lovelace eighteen when they met." Babbage was born on 26 December 1791, and Lovelace on 10 December 1815; in June 1833 his 42nd and her 18th birthdays would still have been six months away. ^ Return - A.L.L., "Notes by the Translator," p. 694. ^ Return

- Quoted in Huskey, p. 315. ^ Return

- Ursula Martin, "Only known photographs of Ada Lovelace in Bodleian Display," Ada Lovelace: Celebrating 200 years of a computer visionary, https://blogs.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/adalovelace/2015/10/14/only-known-photographs-of-ada-lovelace-in-bodleian-display/ ^ Return

- [Charles Babbage,] "Addition to the memoir of M. Menabrea on the analytical engine. Scientific memoirs, vol. III. Part XII. p. 666," The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science, Vol. XXIII, No. CLI, September 1843, pp. 235-239. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=wu.89048308431&view=1up&seq=249 ^ Return

- Thrilling Adventures is also a corrective to the sexualized and misogynistic treatment of Ada in the 1990 William Gibson and Bruce Sterling novel The Difference Engine, in which a steam-powered computer revolution based on Babbage's Engines takes place in Britain in the mid-19th century. In that novel "persistent sexual slurs" are used to describe Ada; "the insistence on misogynistic imagery. . .perpetuates rather than interrogates nineteenth-century stereotypes" (Jay Clayton, Charles Dickens in Cyberspace: The Afterlife of the Nineteenth Century in Postmodern Culture, Oxford University Press, 2003, p. 112). ^ Return

- For information about Ada Lovelace Days, see the website Finding Ada. ^ Return