Rene Clair's early films part 3

Le Million (1931, directed and written by René Clair, after a play by Georges Berr and Marcel Guillemaud)

Michel (René Lefèvre), like all artists, is perpetually broke. But in the middle of a confrontation with the local merchants to whom he owes money, Michel discovers that he has hit the jackpot: the lottery ticket he bought with his last sous matches the winning number. Of course, the attitudes of his creditors are immediately transformed: suddenly nothing is too good for Michel. They just want to see the ticket, to confirm Michel's good fortune.

Realizing that he must have left the ticket in the tatty old jacket he'd asked his long-suffering fiancée Béatrice (Annabella) to mend, Michel rushes to her place—only to discover that the jacket has been taken by Père-la-Tulipe (Paul Ollivier), a rag-picker who hid in her apartment when he was being chased by les flics.

The race is on to find the jacket and recover the winning ticket.

But before Michel reaches Père-la-Tulipe's secondhand shop (which is really just a front for his high-tech gang lair!) the threadbare jacket has been sold to Ambrosio Sopranelli (Constantin Siroesco), a singer appearing at the Opera Lyrique in the (fictional) Les Bohémiens. The jacket is perfect to complete his costume—so authentic!

Everyone descends on the theater to find the unsuspecting Sopranelli and his jacket: Michel and Béatrice, who is a dancer in the opera; Michel's opportunistic roommate Prosper (Louis Allibert), who wants to grab the ticket for himself; Prosper's new girlfriend, the equally opportunistic Vanda (Vanda Gréville); and Père-la-Tulipe and his henchmen.

Backstage before the curtain rises Vanda and Béatrice separately enter Sopranelli's dressing room; each makes a play for the lottery ticket, without success:

Vanda, seeing which way the wind is blowing, then makes a play for Michel:

Witnessing Michel's apparent betrayal, the distressed Beéatrice flees onstage. Michel follows to try to make up with her. But at that moment the curtain rises, Sopranelli and his diva Madame Ravellina (Odette Talazac) enter, and the feuding lovers are trapped behind the scenery.

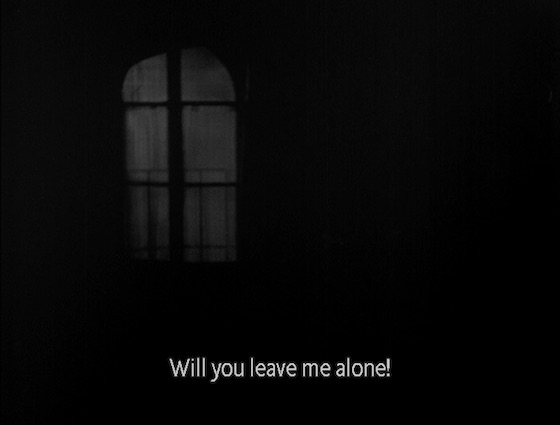

Sopranelli and Madame Ravellina launch into the opening duet, "Nous sommes seuls" (We are alone). The lyrics provide ironic commentary on the lovers' situation; as Michel and Béatrice sit silently amid the artifice of the stage, anything but alone, the tenor and soprano sing "Truth is what we find here."

And because the lovers must remain silent, they can only "speak" through the words of the duet:

As the opera characters reconcile, so do the real-life lovers hidden behind them:

And they are not the only ones who are moved by the music; members of Père-la-Tulipe's gang, in the audience, also find it affecting:

Clair portrays the power of opera to transcend its means of production. We witness Sopranelli's vanity, his bickering with the diva, the bored stagehands who create the magical theatrical effects (the falling blossoms, the waxing moon), and the patent artificiality of the sets. Nonetheless, emotional truth is indeed what we find here.

But there's work to be done: the lottery ticket still hasn't been found. Michel and Prosper sneak out onstage during the performance disguised as extras in a crowd scene, and in the middle of an aria begin a tug-of-war over the jacket (Michel and Prosper are in the broad-brimmed feathered hats):

Mayhem follows (and for good measure, a parody of Harold Lloyd's The Freshman (1925), as one character after another grabs the jacket and tries to escape with it, only to be tackled by the others).

If Sous les toits des Paris was inspired by street-singers, Le Million is not only set in the world of comic opera, but makes use of its techniques—including occasional songs. Père-la-Tulipe's henchmen begin their meeting by singing a rousing anthem of class solidarity:

But despite the film's many virtues, the comic-opera ambience also makes it ultimately feel a bit lightweight. Père-la-Tulipe's gang may find themselves tearing up at the opera; we're in no danger of doing the same over the fate of Michel, whatever it turns out to be. His world is too unreal, and Michel himself is a bit of a heel, with an artist's wandering eye (and hands, and lips). He will probably make Béatrice miserable. Apart from under-appreciated Béatrice, only two other characters earn our sympathy: Père-la-Tulipe, who upholds the thieves' code of honor, and an increasingly exasperated cab driver (Raymond Cordy), whose comic despair mounts along with the unpaid fare on his long-running meter.

Clair may have recognized that Cordy's rumpled Everyman was one of the best things about Le Million, because he cast him in next film as well, his masterpiece.

Next in the series: À nous la liberté (Give us freedom! 1931)

Last time: Sous les toits de Paris (Under the Roofs of Paris, 1930)