A question of decency: Sharafat

|

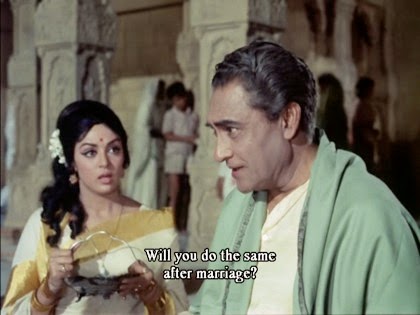

| Hema Malini as Chanda in Sharafat |

And yet the father comes to recognize that her love for his son hasn't arisen from financial calculation, but from true emotion. Still, he has to separate them, or the family will be caught in a devastating scandal. In a heart-wrenching scene, he begs the woman to leave his son as the truest expression of her love for him.

Torn, the woman at first resists. But her growing realization of the ostracism and financial ruin that threatens to encompass her lover's entire family brings her to an anguished decision: she must give him up forever.

In La Traviata, Verdi built an entire opera around this scene. It is also at the core of the novel and play on which La Traviata was based, La Dame aux camélias (Lady of the Camellias) by Alexandre Dumas fils.* But in director Asit Sen's Sharafat (Decency, 1970), this scene is only the pre-credit sequence. It's like an opera in miniature: just a few minutes long, packed with emotional nuances and subtle shifts in power, and giving a hint of the wild ride that will follow.

The writers of Sharafat, Mahesh Kaul, Nabendu Ghosh, and Krishan Chander, add another twist to the story: the woman, Kamla, and the son, whom we come to learn is Jagat Narayan, have an infant daughter together; when Kamla agrees to end the relationship, she realizes that it will mean that their daughter will never know her father.

Twenty years later Jagat Narayan (Ashok Kumar) has become a leading politician. He is also the respected father of the beautiful Rekha (Sonia Sahni) and guardian of Rajesh (Dharmendra). Rajesh is an orphaned boy brought up in Jagat's home who has just earned his Ph.D and become a college professor.

Rajesh discovers that his students are sneaking out at night to visit the pleasure quarter and watch the beautiful dancer Chanda (the beautiful Hema Malini).

Chanda is, as we suspect, Kamla and Jagat's daughter, who has been forced to take up her mother's profession.

Rajesh goes to Chanda and urges her to turn his students away; they are the "innocent children of decent families," he tells her, and are the "future of the nation."

But these "decent" young men spend their time drinking and carousing. They have no interest in learning; they are marking time until they graduate and move into jobs arranged for them by their rich fathers.

Chanda, though, is hungry for the education that she was forced to give up when her mother died and she was taken in by the brothel keeper Kesarbai.

So she agrees to do as Rajesh asks—if he will teach her the same things he's teaching the students. And although he's suspicious of her motives, and she's angered by his prejudices, a pact is sealed between them.

Rajesh begins visiting Chanda every day to give her lessons. At first Chanda uses her professional wiles on him, teasing and flirting as she reads erotic poetry (the only books in the house). Rajesh is not amused:

But soon Rajesh and Chanda realize that they've misjudged each other: she is really sincere in her desire to learn, and he is really sincere in his desire to help. They strike up a true friendship—which slowly begins to deepen into love. This was perhaps the first film of this famous jodi, and their famous chemistry is already apparent.

Rajesh discovers that Chanda's only hope for learning her father's identity is Kesarbai, but the brothel keeper refuses to reveal it: that knowledge, which she constantly promises to tell but then never divulges, is her only hold over Chanda. Kesarbai is aware of the growing affection between Chanda and Rajesh, and, recognizing it as a threat to her livelihood, tries to warn him off:

One day, after Kesarbai has refused again to tell Chanda her father's name, Chanda shows Rajesh the only memento she has of her father: a signet ring. Rajesh is stunned—he recognizes the swastika it bears as the symbol of the Narayan family. He immediately realizes that her father must be Jagat, the second father to whom Rajesh owes everything.

Jagat has his own plans for Rajesh. His daughter Rekha has long been in love with him, and Jagat wants them to marry:

Rajesh recognizes that the stakes are very high for everyone involved, but his sense of sharafat demands that he ask Jagat about Chanda. But when he shows Jagat the signet ring, Jagat is dismissive:

After Rajesh leaves, though, we see that Jagat is haunted by his guilty memories:

The next day Jagat goes to the temple. There he encounters Chanda, although neither of them knows who the other one is. The temple singer (Indrani Mukherjee) sings, "Giver of life, you are the father of the entire universe [Jagat]...I am your child":

The excellent music of Sharafat is by Laxmikant-Pyarelal, with lyrics by Anand Bakshi; Lata Mangeshkar is the playback singer.**

Jagat is touched by Chanda's obvious distress at the song, and by her devotion. He strikes up a conversation with her as they are leaving the temple. But as they descend the steps, they meet Rekha. Jagat asks where Rajesh is, and mock-scolds Rekha for leaving him behind.

As Chanda's face reveals all too clearly, this is the first she's heard of Rajesh's engagement. She flees the temple, and Rajesh, in tears. The next time Rajesh goes to visit Chanda, he discovers that she has gone back to performing for customers, and is about to be sold to a rich merchant:

In a world in which Rajesh and Chanda must run a gantlet of hypocrisy, intolerance, and, ultimately, violence, and in which the "decent" people include the rapacious rich, corrupt politicians, and their dissolute, loutish offspring, Sharafat asks an uncomfortable question: who is really decent?

For an additional perspective, see Memsaab's typically insightful and entertaining review of Sharafat.

--

* Here is a still from the equivalent scene in Camille (1936), based on the Dumas stories, starring Greta Garbo as the courtesan Marguerite Gaultier and Lionel Barrymore as Monsieur Duval:

This scene is also a key moment in Anthony Trollope's novel The Last Chronicle of Barset (1867), in a chapter which was likely written after Trollope saw a performance of Verdi's opera; see The Victorians and opera: Trollope meets Verdi.

** Apologies for the hideous Ultra icon. Where possible I link to versions of songs that don't disfigure the image, as Ultra routinely does.