Opera Guide 5: L'incoronazione di Poppea

Claudio Monteverdi didn't invent opera, but with librettist Alessandro Striggio he did create its first masterpiece, L'Orfeo (Orpheus, 1607), and with librettist Ottavio Rinuccini its first hit song, Arianna's lament from L'Arianna (Ariadne, 1608). What's even more remarkable, though, is that at the end of his long life he returned to opera and surpassed his previous achievements, composing two of the greatest operas ever written: Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patria (The Return of Ulysses to his Homeland, 1640) and his final work, L'incoronazione di Poppea (The Coronation of Poppea, 1642). (I will write about Il ritorno d'Ulisse in a future Opera Guide.)

Claudio Monteverdi didn't invent opera, but with librettist Alessandro Striggio he did create its first masterpiece, L'Orfeo (Orpheus, 1607), and with librettist Ottavio Rinuccini its first hit song, Arianna's lament from L'Arianna (Ariadne, 1608). What's even more remarkable, though, is that at the end of his long life he returned to opera and surpassed his previous achievements, composing two of the greatest operas ever written: Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patria (The Return of Ulysses to his Homeland, 1640) and his final work, L'incoronazione di Poppea (The Coronation of Poppea, 1642). (I will write about Il ritorno d'Ulisse in a future Opera Guide.)

L'incoronazione di Poppea ends with "Pur ti miro" ("I gaze at you"), one of the most gorgeous love duets in all opera. It’s also one of the most perverse. The two characters involved are the Emperor Nero (yes, that one) and his new Empress, Poppea. Even without knowing anything more about the opera or Roman history, this duet might make you feel a bit uneasy. Nero was evidently not a good guy, and your awareness of this doesn’t make this beautiful duet less beautiful, exactly, but does give it a strikingly dark undertone.

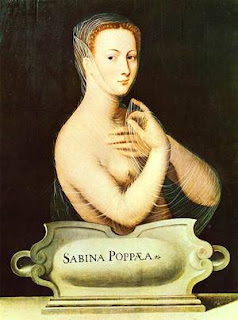

Of course, Poppea isn't the only opera in which beautiful melodies are the vehicle for words or situations that are anything but. This disjunction is especially apparent in Poppea, though, which features a set of perhaps the most cynical and corrupt characters in all opera. Poppea herself is a ruthless minx who uses her lovers as mere stepping-stones to achieve her true aim: becoming Empress of Rome. Her elderly nurse Arnalta (usually played by a male tenor in drag) gives her comic and highly graphic advice about sleeping her way to the top. Even the relatively sympathetic characters, Ottavia (Nerone’s current, but by the end of the opera ex-, wife), Ottone (Poppea's ex-boyfriend, dumped for Nero), and Drusilla (Ottone’s ex-girlfriend, dumped for Poppea), are brought together in a conspiracy to murder Poppea.

And then, of course, there's Nerone (the Italian form of Nero). He sleeps with his subordinate Ottone’s lover Poppea, orders his disapproving advisor Seneca to commit suicide, and banishes Ottavia, Ottone, and Drusilla to exile. So the loving triumph of Nerone and Poppea at the end of the opera is complicated, to say the least, by everything that we’ve seen come before--and everything that Roman history tells us will come later. If the classical sources such as Tacitus are to be believed, the historical Nero killed his mother Agrippina, whose murderous machinations had made him emperor at 16; poisoned his stepbrother and rival for the throne Britannicus; ordered his wife Ottavia to be slain by the soldiers who were escorting her to exile; kicked Poppea to death while she was pregnant with his child; and fiddled--or rather, played the lyre, the violin not having been invented yet--as the fires set on his orders burned vast areas of Rome to the ground. Figuratively, as they sing so gloriously of their love, Nerone and Poppea are surrounded by the bodies of their victims, and this moment of Poppea's triumph is shadowed by our knowledge of her later violent death.

Knowing that listeners couldn’t help but experience some cognitive dissonance, Monteverdi* included some musical dissonance to underline it. As Nerone and Poppea sing “Più non peno, più non moro” (“No more pain, no more death”) their voices clash on “pain” and “death.” The opera may be ending “happily” but there will be plenty of pain and death to follow.

That dark undertone is emphasized by director Klaus-Michael Grüber in this version of the final duet from the 2000 Festival d'Aix-en Provence. In a debatable choice, Grüber drains the interaction of Poppea and Nero of all sensuality or passion; nonetheless, the music remains ravishing. Poppea is sung by soprano Mireille Delunsch, Nerone by mezzo-soprano Anne-Sofie von Otter; Marc Minkowski conducts Les Musiciens du Louvre:

You might wonder why Nerone is being sung by a woman in the video clip posted above. The part of Nerone, like almost every other leading male role in opera for the next 100 years, was written to be sung by a castrato--a singer who, as boy, had been castrated before his voice changed. Castrati were the heroes in opera because their voices combined the high, pure pitch of a female soprano or alto with the lung power of an adult man. In fact, castrati could sing louder and sustain notes longer than unaltered adults; there’s a famous and probably apocryphal story about the eighteenth-century castrato Farinelli outdueling a trumpet. Castrati were the most skilled singers of their day, capable not only of rapid, intricate runs and breathtaking high notes, but of lyrical, affecting slow singing. Castrati also tended to grow quite tall, and so had suitably heroic stature.

While it may seem odd to us that Nero and other operatic villains and heroes were sung by men with high voices, it wasn’t incongruous at all to early operagoers. If opera is designed to showcase great voices, castrati had the most astonishing voices ever. The Baroque obsession with soprano and alto voices meant that both male and female characters sang in that range, and so all sorts of gender-bending took place onstage. Women often played men: when, for example, Handel was unable to find a castrato for the male title role of Radamisto (1720), he cast the soprano Margherita Durastanti in the role. So having a woman sing a male castrato role accords with the practice of the time more faithfully than using a male counter-tenor or transposing the role into the tenor or baritone range.

Opera may depend for effect primarily on the music, but one of the things I find most compelling about Poppea is how good the words are. Over the course of the opera librettist Giovanni Busenello gives every character their due: we see flashes of magnanimity in Nerone, murderous jealousy in the “good” characters Ottavia and Ottone, and the delightful shamelessness of Poppea herself. There’s a scene where Ottone, who has discovered that he’s now Poppea's ex-lover and is being blackmailed by Ottavia to kill her, asks his former girlfriend Drusilla for help. Drusilla has kept a torch burning for Ottone, and she’s overjoyed when he comes back to her. But she can’t quite believe it: “Do you really love me?” she keeps asking, and Ottone, unwilling to disabuse her, replies “I need you, I need you.” After Drusilla leaves, he confesses, “Drusilla’s name is on my lips, but Poppea's is in my heart.” If you’ve ever been in the position of choosing to believe a romantic declaration that you knew deep down was insincere (or have ever been in the position of offering one) that scene can be pretty uncomfortable.

I haven't yet seen a fully satisfying video version of Poppea. The Peter Hall/Raymond Leppard production, the sumptuous Jean-Pierre Ponnelle/Nicolas Harnoncourt version, and the Michael Hampe/René Jacobs version all feature tenors, not sopranos, in the role of Nerone. Transposition plays havoc with Monteverdi's harmonies, particularly in the all-important Nerone-Poppea duets, and so I can't fully recommend any of them. Despite its deliberately passionless final duet, the Grüber/Minkowski version seen above at least promises some excellent singing. And the 2008 Robert Carsen/Emmanuelle Haïm production from Glyndebourne which has just been released on DVD looks very promising; it features Danielle de Niese, a singer who seems born to play the kittenish Poppea.

I haven't yet seen a fully satisfying video version of Poppea. The Peter Hall/Raymond Leppard production, the sumptuous Jean-Pierre Ponnelle/Nicolas Harnoncourt version, and the Michael Hampe/René Jacobs version all feature tenors, not sopranos, in the role of Nerone. Transposition plays havoc with Monteverdi's harmonies, particularly in the all-important Nerone-Poppea duets, and so I can't fully recommend any of them. Despite its deliberately passionless final duet, the Grüber/Minkowski version seen above at least promises some excellent singing. And the 2008 Robert Carsen/Emmanuelle Haïm production from Glyndebourne which has just been released on DVD looks very promising; it features Danielle de Niese, a singer who seems born to play the kittenish Poppea.On CD, Gabriel Garrido conducts the Ensemble Elyma in a lushly recorded version on the K617 label. His cast is packed with early music luminaries such as Guillemette Laurens (Poppea), Gloria Banditelli (Ottavia) and Emanuela Galli (Drusilla), and to my ears they offer a strikingly beautiful if somewhat emotionally cool performance. My first choice might be the live recording with the English Baroque Soloists conducted by John Eliot Gardiner on Archiv, featuring Sylvia McNair as Poppea, Dana Hanchard as a fierce, masculine-sounding Nerone, and Anne-Sofie von Otter as Ottavia. It has a leaner, sparer sound than the Garrido version, but Gardiner turns the emotional temperature up a notch. You won't be disappointed by either version.

* Early music conductor and scholar Alan Curtis has researched the provenance of “Pur ti miro” exhaustively, and come to the conclusion that it is probably not by Monteverdi at all. Instead, Curtis thinks that portions of the existing scores of Poppea were written or revised by younger composers, possibly including Francesco Cavalli, Benedetto Ferrari, and Francesco Sacrati. It is Sacrati who Curtis nominates as the most likely composer of Poppea’s final scene, including “Pur ti miro.” However, who contributed exactly what to the final opera may never be known. Since the vast majority of the music of the opera seems to be by Monteverdi, and there is no definitive answer to the question of whether or how other composers were involved, I’ve continued to attribute this aria and the opera as a whole to Monteverdi.

Update 25 August 2009: We've just seen the DVD of the 2008 Glyndebourne production, and it's excellent. Danielle de Niese is an exceptional Poppea--she not only sings the part beautifully, but the camera catches her many subtle and telling shifts of expression. Alice Coote convincingly portrays a particularly brutal Nero. The historical Nero was only in his 20s when the events of the opera took place, and Coote plays Nero as a tyrant who has never outgrown his adolescent petulance. Emmanuelle Haïm leads the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment in a thoughtful and beautiful realization of Monteverdi's score. Finally, Robert Carsen's production is simple but effective--particularly in the closing moments. Highly recommended.

Update 24 May 2015: Alice Coote has written a fascinating article on playing male roles, "My Life As A Man" (The Guardian, 13 May 2015), which includes a video of the final duet from the Glyndebourne Poppea. From the article:

...I, by necessity, have had to dwell in a place where my mind feels increasingly separate from my sexual body. It has made it complex for me to return to daily life as a woman: I feel in sharp relief the way a heterosexual, bisexual, homosexual or transgender woman’s personal and public relationship power is utterly unlike that of a heterosexual, bisexual, homosexual or transgender male’s expectations and power relationship to the world. Cross-dressing on the stage reveals less to me about gender than it does power.

...Gender-bending sometimes seems to sexualise the performer. I have been on the receiving end of many forms of sexual fascination in response to my trouser-wearing in opera, mainly from women and gay men. It may be that I and other singers in similar roles appear stronger or more powerful or more sexualised because of our awareness of how to use our bodies and play with the idea of male sexuality – and that empowerment elicits excitement. In stepping outside our gender we also step beyond the social rules to which so many of us adhere, and this “transgression” is thrilling, even sexually liberating, for an audience.

I in turn have had to question my own femininity and what it consists of, both for me personally and for others, and to ask which part of me defines my female identity, and in what degree. Is it my body, my mind, my chromosomes alone, or the conditioning of society?

Lovely post thanks so much - and yes the Glyndebourne Poppea is really worth a look, Alice Coote is a wonderful example of what a mezzo an do with Nero!

ReplyDeleteThanks for correcting my oversight, PM--I should have mentioned the Glyndebourne production's Nero! Alice Coote was an excellent Ruggiero in the San Francisco/Stuttgart Opera's wonderfully performed/appallingly directed Alcina a few years ago; those who are curious can see an excerpt here. I'm very much looking forward to her Nero.

ReplyDeleteThanks again for your comment, and let me take the opportunity to encourage everyone to visit the marvelous Se Vuoi Pace.

great post. really helpful! i agree, the Glyndebourne is worth a look!

ReplyDelete